Photography traditionally addresses an object or living being, some specific motif, bringing it into the field of vision of the camera at a certain place, against a certain background, at a certain time. It is not merely a question of the photographer's own approach and style. Instead, it is a "classical stance" or even a kind of "classicism" so firmly inscribed within the medium of photography that it seems inherent. The camera is directed at a specific object in the world. Selecting that object and releasing the shutter make it a specific and unique object.

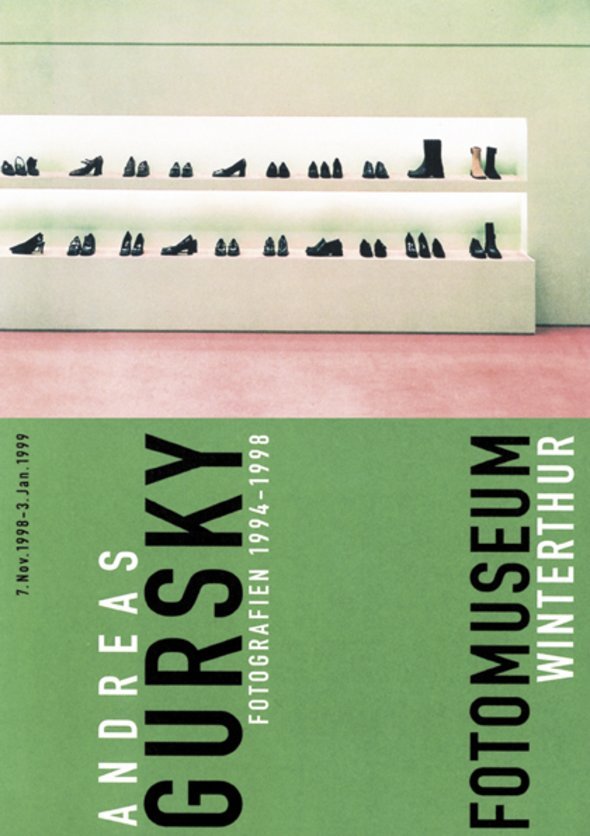

It is in this spirit that Andreas Gursky travels the world, choosing a certain motif at a certain time in a certain place. Places of production, for example – the means of production in contemporary industries – or places where commodities change hands – cargo ports, consumer goods on display, banks, stock exchanges – or places where people come and go – hotels, harbours, shipping ports, airports – leisure in the broadest sense, people strolling in a garden, skiers, ravers. He also presents the fora of politics and the temples of art. It is in this spirit that he lends his photographs their simple, descriptive titles such as Times Square, Bundestag, Union Rave, Prada II, Engadin, Rhine, Hong Kong Stock Exchange, Atlanta, or Turner Collection, adding the year to fix them in time.

In contrast to all that has been said and, it would seem, in complete contrast to what is generally regarded as the very essence of photography, the goal pursued by Andreas Gursky is a different one. He may go to certain places, but rather than trying to capture a motif against a background, he seeks to point out constellations and superimposed or underlying structures, and to visualise the correlation between social events and actions. On the one hand he does so by bringing together many individual details to create a kind of photographic map, and on the other hand through a concentration of details that appear symbolically laden, yet do not quite reveal their meaning. Admittedly, his photographs are taken at a specific time, in the here and now of a prosperous, mobile, post-industrial capitalist society – even the landscapes in his photographs have to be regarded in this way – yet he seeks to expand the notion of a fixed point in time, transforming it into something universal rather than narrative.

In terms of photography, Andreas Gursky pushes the medium to its limits. In terms of the picture in general, he undertakes abstractions and constructions. He abstracts from the specific to the general or he constructs something general out of the many existing concrete details. In terms of content, Andreas Gursky seeks universal signs. He looks for the everyday, repetitive signs that reflect the rules and structures of social interaction in all that is specific, quotidian and contemporary. Paradoxical as it may seem, these are the two extremes between which he builds up a highly charged atmosphere where the spectator, moving around in front of and among his large-scale works, is torn between an awareness of specific small detail and a sense of some greater universal order, grasping its significance only to lose the thread again immediately. It is a world order mirrored in the absolute clarity of the sky, in the midst of a crowd, in the teeming intersection, in the sheer abundance of reality. Andreas Gursky is like a history painter portraying the scenes of historic events, unromantically aloof and coolly analytical, with a thirst for knowledge and a critical eye, and with a tendency towards universal thinking. Invariably, however, from first to last, he endeavours to achieve an extraordinarily powerful sense of presence in his photographic images.

Urs Stahel, Director