The picture in the twentieth century: how earnestly it has been treated at times. Precisely as if it were the true prospect of the world, as if it were a Commandment, a training field or a template for conducting the world. Precisely as if the white canvas were the equivalent of high, pure, absolute time; the black canvas of empty time, the void; the red one of active, bloody time—abstract canvases, yet laden with profound meaning. Pictures and attitudes have been so fervently earnest, so ardently poetically earnest, so intellectually earnest, so steamily sublimely earnest that not even the greatest sceptics have managed to resist their charms. The declarations of Marinetti (‘Futurism rests on a complete renewal of human sensibility.’[1]), of Malevich (‘In the wide space of cosmic celebrations, I shall establish the white universe of Suprematist nonobjectivity as the manifestation of the liberated void.’[2]), of Max Bill (‘Concrete art … should be the expression of the human mind, devised for the human mind, and shall be of an incisiveness clarity, of a perfection, that can be expected of works created by the human mind.’[3]), of Richard Paul Lohse (‘Serial and modular methods of design are, through their dialectical character, parallels to the expression and activity of a new society.’[4]) and, finally, the laconic, absolute declaration of Barnett Newman (‘The sublime is now.’)— like these and many other manifestos, pictures have presented themselves and been ‘interrogated’ in a similar fashion. Almost Gnostic braggadocio again in an Agnostic age. Neither the crusading earnest, which caused avant-garde movements to collide head-on, nor the reversal of the primal message (‘Thou shalt not make any graven image.’[5]) would have been particularly surprising, had there not been such a profound gap between Utopian claims (After this picture the world will be different.) and historical events (Can there be poetry after this world, after Auschwitz?). But as it stands the earnestness arouses not one but two suspicions. Have pictures possibly become an important military side-show; have they become a necessary psychic fixation in response to this century’s historical explosions, which could hardly have been more atrocious or had more violent economic consequences? The picture: Has it been taken so seriously not only for what it is, not only as a metaphor, but rather as a refuge and a surrogate of the world, though still served up with the utter earnest of ‘reality’, the entire thrust of utopian projection and in the rhythm of social time. The picture as a kind of deputy for reality?

Art is learning to laugh again.

The artists that followed were also serious but they have launched a campaign against crusading earnest (see above). In addition to fields of endeavour that generate a supplementary, de-constructive counterworld, mention will made of mountains that are no mountains, accidents involving sausages and burning papier-mâché, of severed women’s bodies, of lost nature and lost truth, of photography that is the drawing of a drawing that is the photograph, of appearances that deceive, and of pure appearance, of the fake and the simple celebration. If there were manifestos, they would say: Appearances deceive, and that’s fun too; style is done with, thank God; the world is mutating, so let’s watch. Yes, it is a game (‘In the wake of modernism, art has learned to laugh again.’[6]), but a serious one. Yes, there will be talk in the following of a kind of pictorial magic, but also of fake magic, of make-believe and fibbing. Flesh and blood but not our own. Curious vows, fake pigs – and a rabbit, in fact two of them, mirrored, out of a full book, not an empty hat. And the aura, the sublimity of the light-flooded dome? It rises above a plastic colander, shot with a Polaroid camera, also made of plastic, in front of neon lighting. The picture and the dominance of form are often at stake and, with them, our perception, our earnest, our search for the straight and narrow path, our search for a formalised work.

Wham, wham, deconstructed with a bang. Between 1955 and 1995, and peaking in the seventies, perception and images were subjected to widespread, enduring, earnest examination. On the one hand, vision and recognition were investigated and analysed; on the other, belief in the picture and its reality began to crumble. Photography thus rejected the single shot in favour of rows, sequences, and series, while painting broke out of the confines of the frame, spilling over onto walls, into rooms, and out into life. In both cases, the aim was to demystify, to purge work of meaning and emotionality. From now on, it would suffice to have a vehicle (frame, canvas, photographic paper), a surface (ground, primer or emulsion) and a few thoughts, attempts, or aspects.

The Vanguard

Before venturing further, reader, it is worth remembering that there were isolated thrusts in this direction as early as the beloved-belittled kidney-table fifties. Taking up where twenties’ dada left off, a young upstart literally hooked the doctrine of pictorial composition up to the mains-stream. Jean Tinguely, an engine and batteries set the ball of state art in motion. ‘Meta-Malevich’ was born, a series of 18 black wooden boxes, each with different combinations of white metal elements—triangles, circles, pointer-like rectangles, rubber belts, metal fittings, engines, sometimes 110, sometimes 220 volt, 41 or 50 sq cm in size and 10 to 11 to 12 cm deep. Later, kinetic, polychrome reliefs were added. While Tachism and Art Informel joined the ranks of absolutist detractors of prevailing norms, both past and future (composition made absolute in Constructivism; colour made absolute in monochrome painting; the expressive gesture and energy made absolute in Tachism and Art Informel), Tinguely gave this claim to the absolute a special twist, undermining a school with irony and himself with playful humour. This presaged but did not immediately cause the collapse of the doctrine of composition, for it had just recently been granted social and bourgeois sanction as ‘Good Form’.[7] But the ground had already been prepared for a way out of absolutist claims. André Thomkins and his (surreal) transformations, his rapport, his weaving pattern that dissolved all centres; Dieter Roth, the lingual magician in the medial arena, and his inversions, his melting of time and sequence; Daniel Spoerri and his trap pictures, tableaux pièges, were other outstanding, but isolated exponents of a kind of neo-dada in the fifties and sixties.

The Sixties and Seventies

And then in 1964 Peter Knapp’s 36 shots of Swiss flags fluttered at the Expo 64; Ben Vautier assured the canvas in his own handwriting that it is indeed a toile (and three decades later that La Suisse n’existe pas); viewers were blinded by Samuel Buri’s garishly painted and enlarged halftone chalets in 1967; Jean-Frédéric Schnyder’s record-cover art toyed with vision and fetishes in 1967-69, Burkhard/Raetz turned reproduction into object in 15 large-format photo canvases of 1969/70 (black-and-white shots of everyday things and places—studio, kitchen, double bed, curtains, a piece of paper— enormously enlarged on canvases and pinned to the wall); Camesi visualised the point de conditionnement in 1969 and the dimension unique in 1971 (the same portrait in frames of different colours); Herbert Distel’s empty gold frame, 220V, also made in 1971, illuminated itself; and, finally, Heinz Brand devoted himself from 1965 until well into the eighties to photographic studies of the relativity of seeing, the idea of material reality and the representation of both. Aldo Walker’s and Rolf Winnewisser’s independent and occasionally collaborative ‘Vagrants in Images’[8] and Christian Rotacher’s small installation of 1978 (a circus-like scene with a canvas placed between two tall stools and titled Fontana, the tiger, the first to jump through the screen; all we have left are the rings of fire, in ironic reference to Lucio Fontana’s act of slicing the canvas) conclude this cross-sectional review.

In short, the late sixties and seventies were a time of rejection for many artists: rejection of abstract, pure, objectivity-seeking modes of composition and their conceptual underpinnings; of the work as a self-contained, absolute entity; of the canon of art-worthy materials; of notions of style. Further, artists disavowed the grand form, the grand narrative, overarching truths, the absolute, in order to seek insight into the conditions of their own actions and the limitations of the message. ‘Postulates are no longer accepted as supra-individual truths but instead re-evaluated in terms of their functioning and their legitimacy. This individual anarchy entails a “de-colonialisation” of the individual from outside postulates, from outside control, from conventions and contracts.’[9] And they were a time of ceaseless exploration, of thinking about and questioning the world, perception, art, the idea of the image and its composition.

The works—mainly small drawings, modestly undemonstrative aquarelles, odd little objects, notebooks—were primarily the field, the means and the record of explorations.[10] Photography was increasingly deployed to similar purpose, as a means of notation, documentation, construction, staging, but also as a means of playing with itself as subject, as a perspectival prize piece. For once there was a rapport between the concerns of photography and art. Christian Vogt’s time-space sequences, his exploratory game with picture frames, and Valdimir Spacek’s studies in light and space are good examples.

Hugo Suter, Markus Raetz, Fischli Weiss, Gérald Minkoff

Artists, representing the seventies and, of course, themselves as well, include Hugo Suter, Markus Raetz, Fischli Weiss and Gérald Minkoff. Suter’s works stand for the persistent study of perception, Markus Raetz’s oeuvre for the playful treatment of perception and image, Peter Fischli and David Weiss for the introduction of refreshingly frivolous pictorial narratives produced with meagre means, Gérald Minkoff’s works for the appropriation of history via existing visual records, using both modern and archaic means. The title of two works by Hugo Suter, Surface Divers, is a contradiction in terms, an oxymoron. The photographs show the reflections of a window on a bright, wavy piece of plastic film. The reflections resemble figures, evoke images of passers-by or dancers—an optical illusion because the impression of things flowing is generated by the distorting effect of the window pane; every change of standpoint creates a different reflection. The contradiction is cancelled out by this optical illusion. ‘Profundity’ is no longer an imperative; it suffices to plunge into the diversity of surface appearances.

Markus Raetz’s Polaroid shots are in a sense preliminary studies and notes for other larger works as well as smaller, self-contained pieces, although the artist himself does not consider them as such. But the snow-covered mountain in Amsterdam, the colander as a light-flooded, coffered dome (and an homage to Schinkel), the little clay figure and the photographed clay figure supporting each other with the palms of their hands, clinging to life, the threefold presentation of a picture through light broken by a prism and the alteration of plasticity depending on how the light passes or penetrates the object—these are magic tricks, which contain, in miniature, a thought that runs through all of Raetz’s work: the act of revolving around one’s own axis while simultaneously revolving around another and another, a second, a third external axis, like planetary systems that keep mutually changing their relative standpoints and yet still determine each other. Raetz’s studies, ranging from observation to construction, address visual phenomena, planes and volumes, shift from literal to metaphorical meanings, from reality to photography, from first to second and third standpoint, thereby demonstrating relativity as a principle that nourishes thought and design. Appearances appear to be so different from what they appear to be—and a small Polaroid picture, 77 x 79 mm, offers inalienable proof: the most beautiful snow-covered mountain, with especially radiant blue skies, is located in Amsterdam.

They are known as the Sausage Series, these ten small, unassuming colour photographs, 24 x 30 cm, that Peter Fischli and David Weiss submitted to the public in 1979. As modest as the series looks, it contains all the explosive implications of the heresy that has ignited everything they have done since, from scenes of the world, moulded out of clay, in Suddenly This Overview, to dances performed by carrots and graters in the photographed series Quiet Afternoon and, finally, their colourfast idylls of agglomerations of 1992. A small (photographed) fire in an oven is titled Among Cave Dwellers; a (photographed) piece of Styrofoam in the water, The Sinking of the Titanic; spruced-up sausages, Vain Bunch or Fashion Show; snow-covered hills made of bedding depict a scene In the Mountains and contain a little Mountain Lake. Other telling titles include The Accident, Blaze in Uster, Pavesi or In Ano’s Carpet Emporium. The heresy forms a triangle: there is the narrative aspect, officially unacceptable in twentieth century art, then, the almost child-like fun on Mummy’s brown mohair carpet and, finally, the use of banal materials—egg cartons, sausages—to depict serious issues such as accidents and blazes. The earnest research of the seventies has been displaced by sheer delight in uninhibited and uncanonical fun.

Gérald Minkoff’s Cameraless Instantphotochemogrammes have been somewhat neglected. They may have seemed too obtuse in 1977 to be perceived with all their implications. The Kodak Instant Pr 10, launched in 1977 in competitive response to the Polaroid SX-70, had to capitulate six years later. During this time, Minkoff produced a very strange series. Using a pasta maker he distributed the chemicals in the photograph without exposing it to the light. He then drew on the back of his ‘instant’ photograph while it was developing—from five seconds of black to 15 seconds of blue to 20 seconds of blue-green to 25 seconds of red, then to yellow and finally to brown. The lines varied in colour depending on his timing. Minkoff calls what he drew D’après (After). Just as drawings were once made after nature and photography also began essentially by making pictures after nature, Minkoff drew into the photograph after the history of photography—after Thomas Eakins’ nude, after Harald E. Egerton’s swinging golf clubs, after Stieglitz’s equivalents, etc. By so doing, he initiated an eminently draughtsmanly and an eminently photographic process, as well as a core method of appropriation: the appropriation of the history of photography in examples, the drawing of the picture through the chemical layer, therefore a mirrored end product: a semiotically brilliant act and a work that could be entitled The Pencil of History, 1977-83, in allusion to the British pioneer, Henry Fox Talbot.

The Eighties and Nineties

Naturally, photography has forged ahead outside of Switzerland as well. Sigmar Polke’s photographic alchemy, William Wegman’s pictorial sequences and enigmas in the early seventies, Jan Dibbet’s ramifications of reality in analogy to the shape of the eye and John Stezaker’s semiotic studies are but a few examples of international experimentation and research into the photographic image. At the beginning of the eighties concentration on the image gave way to the energetic, expressive gesture in photography, but towards the end of the decade it acquired new momentum again under different auspices.

In the Swiss context, attitudes and issues have developed in a variety of directions. Research in the field of painting has been pursued by Rémy Zaugg, Aldo Walker and Rolf Winnewisser; and in the fields of photography and ‘machine engineering, perceptual discourse’ by Claudio Moser, Hans Knuchel, Reto Rigassi and Andreas Hofer. An ingenious mixture of research and play is found in the work of Hannes Rickli, Laurent Schmid, and explosives-sculptor Roman Signer, and also in Olivier Richon’s allegorical, emblematic scenarios, and, in terms of content, in Daniel Buetti’s photo fields of inner and outer skins and Ian Anüll’s style-image-swastika work. The narrative strain has been taken up by Christoph Rütimann in his staged Polaroid shots, by Esther van der Bie, Pipilotti Rist, Istvan Balogh and newcomer Olaf Breunig. The triad research-play-construction has been addressed by Bernard Voïta, Martin Blum, Clara Saner and Chantal Michel; the strategy of appropriation leads to Christian Marclay’s record-cover assemblages, to Rémy Markowitsch’s ‘After Nature’ and to Sylvie Fleury’s and more recently Bürgin/Schoch’s magazine-cover art. A mixture of research and celebration—we are still talking about pictures—is found in the work of Ursula Mumenthaler, Béatrice Helg and Mitja Tušek; and finally celebratory imagery in the work of Balthasar Burkhard, Cécile Wick, Adrian Schiess, Andreas Züst and Michael Biberstein (the latter, primarily in paintings).

Two aspects are worthy of note. First: women are in the great minority on the research side of the scales. In the eighties they found expression above all in body photography or what might be called performance photography. And second: pure research, such as that conducted in the seventies, sometimes with serious educational, didactic ambitions and a claim to the absolute, no longer exists. In a kind of post-conceptual approach to the world and to the making of art, that little twinkle in the eye became a casually friendly, mimetic standard; the quest for self-knowledge no longer caused such anguish, it began to be fun. After all the analysis, the disassembly, the deconstruction, people have begun treating pictures as pictures again, albeit under different auspices: research-game-celebration as a new, up-to-date, pictorial mega-mixture.

Let us take a closer look.

Research and Game

Hannes Rickli describes his installation himself: ‘In a darkened room, a plastic ball slowly revolves (…) around a stable axis. The movement is controlled by the computer. When viewers activate light barriers in the room, the ball starts revolving according to randomly generated parameters that govern the direction of the spin, the velocity and the alternating supply of current. (…) The ball is coated with graphite and records the movements on its own surface by rubbing and sliding at three points of contact. The ball is thus a palimpsest of constantly fragmented and reformed traces. The simultaneous filming of this process can be watched on a large screen.” A reversal of the procedure used by Fischli Weiss seems to be operative here. At great effort, a barrage of technology is set in motion that looks more like a scientific experiment than a work of art. But a closer look undermines this impression. The equipment is hardly state-of-the-art and the installation has not superseded the stage of scotch-taped improvisation. Rickli has always been interested in the parallels between art and science in their quest for knowledge and truth. His Writing Game, as he calls his installation, closely resembles a scientific device for the generation of guaranteed truths. But the genuine investigation of cognitive possibilities has turned into a predispositional, ironic game. What remains are insights into relativity – and seductively beautiful pictures of ‘planets’!

Laurent Schmid from Berne turns blunders into wonders; his protagonists are Partisanen (German slang for specks of dirt on plates that cause a little black dot with a lighter aura around it in the printing process). Schmid has made a series of works with these professional stigmata. The work Lichtenberg Figures from the ‘Static in the Mountains’ series elaborates on this theme. In extremely dry weather, static can interfere with the transport of film in a camera, which shows up as flashes on the negative. Schmid combines this faulty action with pictures of a Spanish electric power plant and urban scenes – with energy produced and energy devoured. A real process and its representation are superimposed.

Celebration of the Image

In the end, research, scepticism and doubt come full circle; they ultimately return to the original situation: here the artist, there the picture, and later a few viewers. But the situation is different after all, because it has been saturated with medial knowledge and reinforced via the detour of research into method, means and cognition. Cécile Wick is one of those artists who subscribe to the original situation: simple camera (a pinhole camera, though this is of minor importance) simple ways, simple pictures: landscapes, of lakes, oceans, of mountains, waterfalls, of the Rhine Falls—and head-(self-)portraits. Single pictures that can easily be enlarged, almost like modules, to form groups. External and internal worlds as common ground, as a rich black-and-white universe, as distilled images. Four horizons, for example, in which depth has almost risen to the surface. Actually two adjoining planes, and nothing else. Confronted with such richly enriched, seductive nothingness, we, the viewers, begin projecting and enthusing.

Cécile Wick’s horizon still maintains a balance between representation and pure, abstract image; in painter Adrian Schiess’s small, 30 x 50 cm colour photographs, representation has vanished altogether. There was once something in front of the camera, a floor, a monitor, but the mode of shooting, specifically the different degrees of blurriness, transform the prosaic subject matter into a celebration of abstraction, into gentle processes or colourful patches—into pure, beautiful appearance.

Staging and Constructing

Fischli Weiss’s introduction of narrative pictorial construction has found a parallel since 1984 in the work of Christoph Rütimann. This artist from Lucerne, known for working in extremely diverse media, known for his precision of concept and design, known for works that essentially orbit around questions of open, floating energy—energy that occasionally liquefies into rivers of precipitation, producing fallout: a weight on a balance, a line on a wall, a curve in space, seismographic notations on paper—, this Christoph Rütimann expresses the poetic side of his nature most intensely perhaps in his Polaroid work, staged out in the snow during many a winter holiday. The most recent series, 42 Polaroids, 42 different stories in the snow, is more narrative, more theatrical than ever. It seems that the snow makes an excellent, semi-translucent, semi-present stage for the most varied picture stories, picture puzzles, picture games: little dramas, sometimes including likenesses of himself and his partner; beautiful, enigmatic pictorial configurations put together with fragments of clipped photographs, bits of wood, sticks and tape, yielding, for instance, a kind of wondrous model of a garden with structures of yellow, red or green building blocks facing square, deep-blue ponds. Reversal of scale, fragmented figures and words, real objects and figures cut out of photographs together create a body of poetically enchanting work.

Bernard Voïta takes a more austere approach in his photographs. His work is as meticulously constructed as Rütimann’s, but the intent is less theatrical and more sculptural. While his earlier photographed compositions involved picture plane and spatial depth, the gloss of reproduction and arrangement in a grid, his recent ‘pictorial sculptures’ have become more architectural. They are a stroll through buildings and cities, along motorways, past a petrol station, a brief halt in front of construction sites, before going to the outdoor swimming pool. The small photographs with oversized white margins resemble enlarged halftone dots but as we move closer, they reveal an entire universe. The homo ludens is unmistakable in Voïta’s work, but so is his delight in perfect construction. Fiction with a touch of reality.

Imprints - Picture and Language

In the work of Ian Anüll and Daniele Buetti, picture and language intersect, obstruct each other or lead to an expanded, mutually complementary dimension. Anüll’s work in Graz—four diptychs each consisting of a monochrome painting of the same colour and a changing photograph—is a sarcastic piece of art. In the right place, in Styria, and on the right wall, that of a camera shop, the battle between symbol (swastika) and monochrome plane, between terse, dry unemotional activity and a ‘bundle’ soaked in meanings emblematic and otherwise, is waged before the ‘eye of photography’. Anüll’s signs—‘stil’, ‘style’, ‘estillo’, etc.—painted through years of travel in the language of the respective country and in a matching colour, has provoked vehement contrasts and wild associations. The concept of ‘style’, already burdened with tradition and problematic implications, from the ‘small difference’ to ‘international style’, is now placed by a travelling European, as a painted sign, or rather a connotative bombshell, in the most varied of contexts: between picture and language, between street scene and refined culture, between north and south, east and west, lifestyle and life’s realities, between style and style. Reassessment as an idyllic little image on canvas merely exacerbates the conflict.

Outside and inside skin: Daniele Buetti’s two wall-filling works, Please justice and Good fellows are structurally dovetailed. Please justice, a photographic panorama-like work, combines two outside appearances: that of the city (New York) and that of public speech—the image of a city and typography as imagery. The two aspects blend with varying levels of intensity, but on the whole, language ‘wins out’, i.e. a world visually forged out of instructions, models and orders. One is tempted to toy individually with the numerous photographic-typographic works and to rearrange them: for example, to find a replique for Please/justice: Accept/your/life or We make/you, or another variation: We/deserve/you – and so on.

In contrast Good fellows constricts space, moves the dividing zone up to the ultimate refuge of the individual, to his/her own skin, arm, leg, or still ‘closer’, to the chest. The work started out as a performance in New York, as a marketable commodity: tattooing on the street. The artist found a sequel to it in the superimposition of picture and language, by mutually ‘impacting’ nearest and farthest, tiniest public space (one’s own skin) and the greatest private ownership (the names of global corporations). “Buetti’s company tattoos precisely mark the interface between collective takeover and individualistic self-assertion.”[11] – an interface cross stitched into a painful paradox.

‘After Nature’[12]

Gérald Minkoff ushered in the practice of appropriation; Rémy Markowitsch has made it his central artistic concern. Markowitsch immerses himself in picture books, in the twentieth century’s collective picture archives, in botany books of the fifties, toughening-up courses of the thirties, in the processing of pictures, in their arrangement and sequencing, and in the techniques of printing them. His major project is entitled ‘After Nature’ -- temporally ‘after’, but removed, detached from nature -- and contains a sub heading of landscapes, plants, animals and people. Like so much of his work, ‘After Nature’ functions according to the following principle: Markowitsch treats the prefabricated inventory of culture as a raw product, puts it in the limelight, that is, he illuminates it by mutually superimposing two pictures of the same ‘kind’. The result: His mechanical copy of a mechanistically printed copy of a mechanistically photographed copy of a reality becomes another, independent and at times monstrous pictorial reality, a new creation—similar to the ‘coinages’ bred by humankind in the material, plant and animal kingdoms. Markowitsch plays the roles of a keeper of pictures, a chronicler and Mephistopheles, the most devilish coiner of all.

In conclusion, Martin Blum’s pictorial constructions exploit the entire spectrum of available devices: taking the picture away from its support, cutting it out and placing it in three-dimensional space, rolling it up, putting it in a corner or in a room, using found, printed materials, combining pictorial and non-pictorial materials and, finally, projecting light and shadow to generate the desired volume and depth. And he deploys these means in such a way that one recognises the construct on second sight at the latest, that one follows its manifold structures and plunges into its perceptual abysses.

In short: a few positions from a field in which the picture as a fixed, sanctioned value is questioned, tested and later reinstalled, reinstated in playful, narrative, celebratory form. No longer encumbered with absolute claims, it becomes a fitting contemporary metaphor for life precisely because of its fragility, its delicacy, its artificiality, its humour and its irony. Independent, exciting directions in the world of Swiss art photography.

Translation: Catherine Schelbert

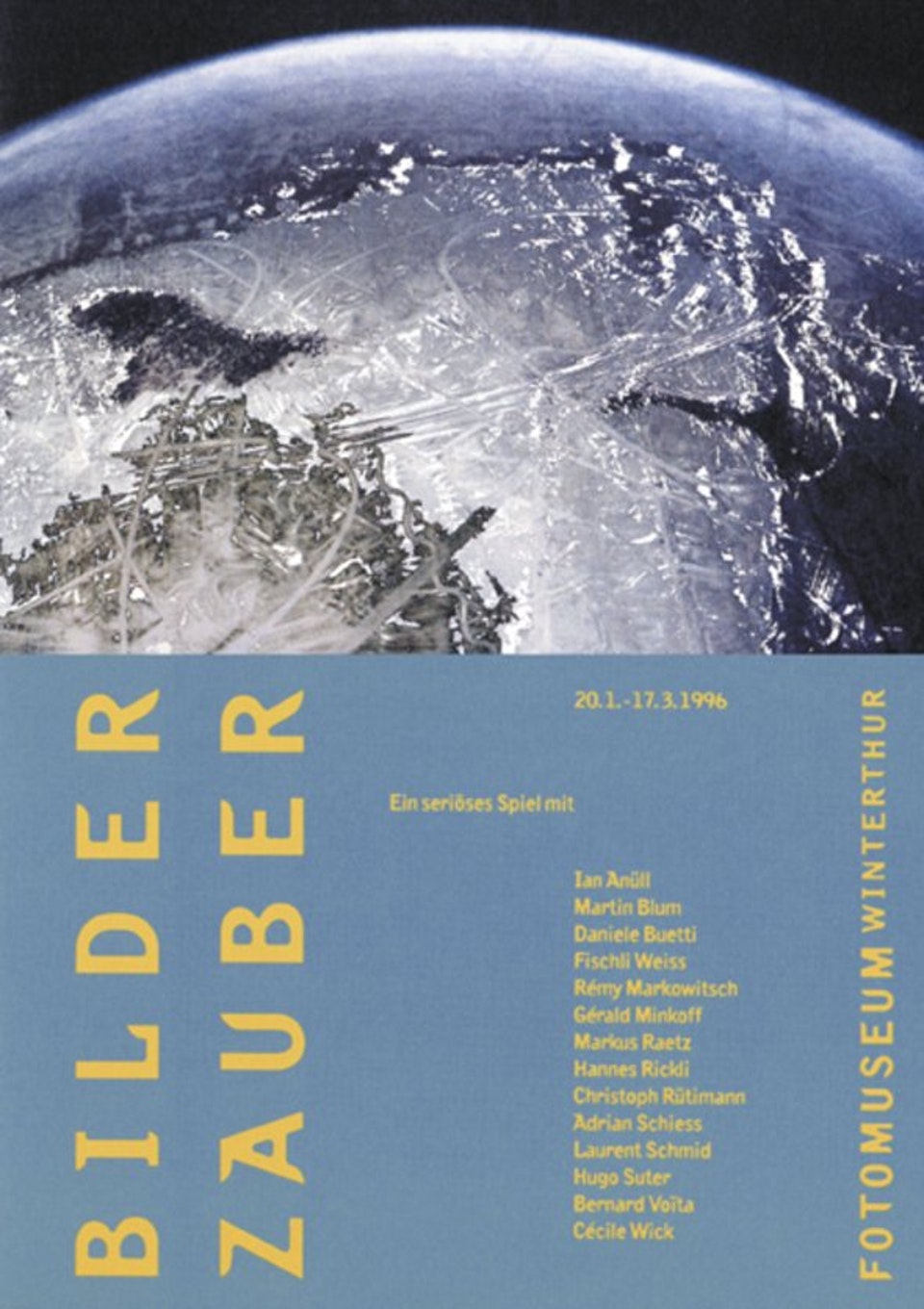

This article is a revised version of an essay, published in the exhibition catalogue Bilderzauber – ein seriöses Spiel, Fotomuseum, Winterthur, 1996.

[1] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, ‘Zerstörung der Syntax - Drahtlose Phantasie - Befreiende Worte - Die futuristische Sensibilität, 1913’ in: Umbro Appollonio, Der Futurismus, Manifeste und Dokumente einer künstlerischen Revolution, 1909-1918, Cologne, 1972, pp. 119 ff.

[2] Kasimir Malevich, The Nonobjective World, 1926.

[3] Max Bill, quoted in: Willy Rotzler, Konstruktive Konzepte, Zurich, 1977, p. 130.

[4] Richard Paul Lohse, quoted in: Willy Rotzler, Konstruktive Konzepte, Zurich, 1977, p. 136.

[5] Exodus, 20: 4. ‘Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth…’

[6] Beat Wyss, ‘Nach der Moderne - die Schweiz z.B.’ in: Beat Wyss, ed., Kunstszenen heute, Ars Helvetica XII, Disentis, 1992, p. 38.

[7] First a famous and then an infamous concept from the field of applied arts in Switzerland, which stresses the rational, functional and also puritanical aspects of design.

[8] ‘Stromern im Bild’, title of a joint exhibition, Mannheim Kunstverein, 1982, pp. 91 ff.

[9] Theo Kneubühler, Kunst: 28 Schweizer, Lucerne, 1972, p. 3.

[10] See also: Urs Stahel, ‘Brennpunkt’ in: Beat Wyss, Kunstszenen heute, Disentis, 1992, pp. 91 ff.

[11] Christoph Doswald, ‘All over. Mimetische Subversion in der künstlerischen Praxis von Danielle Buetti’, unpublished manuscript, 1995.

[12] Also the title of Rémy Markowitsch’s catalogue, Galerie Urs Meile, Lucerne, 1993.