We are gazing at a skeletal structure, at a concrete or reinforced concrete construction in progress. The structure is complete, it has been built, but otherwise nothing is happening on the construction site. The photograph quickly recalls the many single- and two-family homes found all over southern Europe, on the village outskirts, left in the structural phase. The owners scrimp and save their money in the North and spend it in the South, in their original homeland, gradually building, in short steps, a dwelling, a ‘last resort’ where they plan to live after retiring. Only, the house here is much larger, with the aim of becoming, if it is ultimately completed, a large office complex or an enormous apartment building. The open structure without a façade is cordoned off by red-and-white tape or wooden planks and thus marked as dangerous. Caution: danger of falling. Caution: no railing yet.

Frank van der Salm photographed and cropped the skeletal structure in such a way that we cannot identify and classify it as a free-standing building. Rather, the outer walls, the roof, and the floor on which it stands also simultaneously function as the picture frame. If we weren’t able to look through the building at the suggestion of a diffuse landscape, it could easily have the size of a shoe box. Because the building in the photograph has been shot flush with the picture plane, it appears like a complex screen that on the one hand shows a gridded vista and on the other hand obstructs, indeed, makes a clear view virtually impossible.

There is a whole series of all-over pictures in Frank van der Salm’s oeuvre like this photograph titled Grid, from 2003. Take, for instance, Flatland, from 2012. Here, too, we again see a clear, geometric structure that unfolds before our eyes like a collapsible box and seems to form a structured volume. The façades are gridded in different densities, either more generously or smaller. Yet the building – or thing – in this photograph, by contrast, seems opaque. Here, we see only the closed structure but not into or through it. We suspect that the material of this almost repellently closed, blind structure is either cement, concrete, or – but then far more volatile – sand. The light grey, dirty-warm material allows for both readings. One time solid, ‘forever’, and then one time ‘see you later, until the next time it rains’. One time a standing sculpture, the second time a recumbent relief in the sand that on the left side has already started to crumble slightly.

The work Condominium, from 2010, is likewise done in an all-over manner, up to the edge, cropped by the camera’s rectangular screen template such that the building isn’t presented in its context but extracted from it, and not in its entirety but truncated. We see three vertical structures that overlap one another and together form a large luminous body. The blurriness of the corpus on the outer right makes it appear as if it’s motion. All three together seem

like a large geometric lantern that glows from within itself. Nearly all the lights are turned on. They make the office complex shine grey-blue-greenish from the inside, radiating outward. Three bodies, placing, pushing themselves together, posing in the picture plane of the camera. Living, from 2007, Mirage, from 2006, and Park, from 2002, all belong to this group of works.

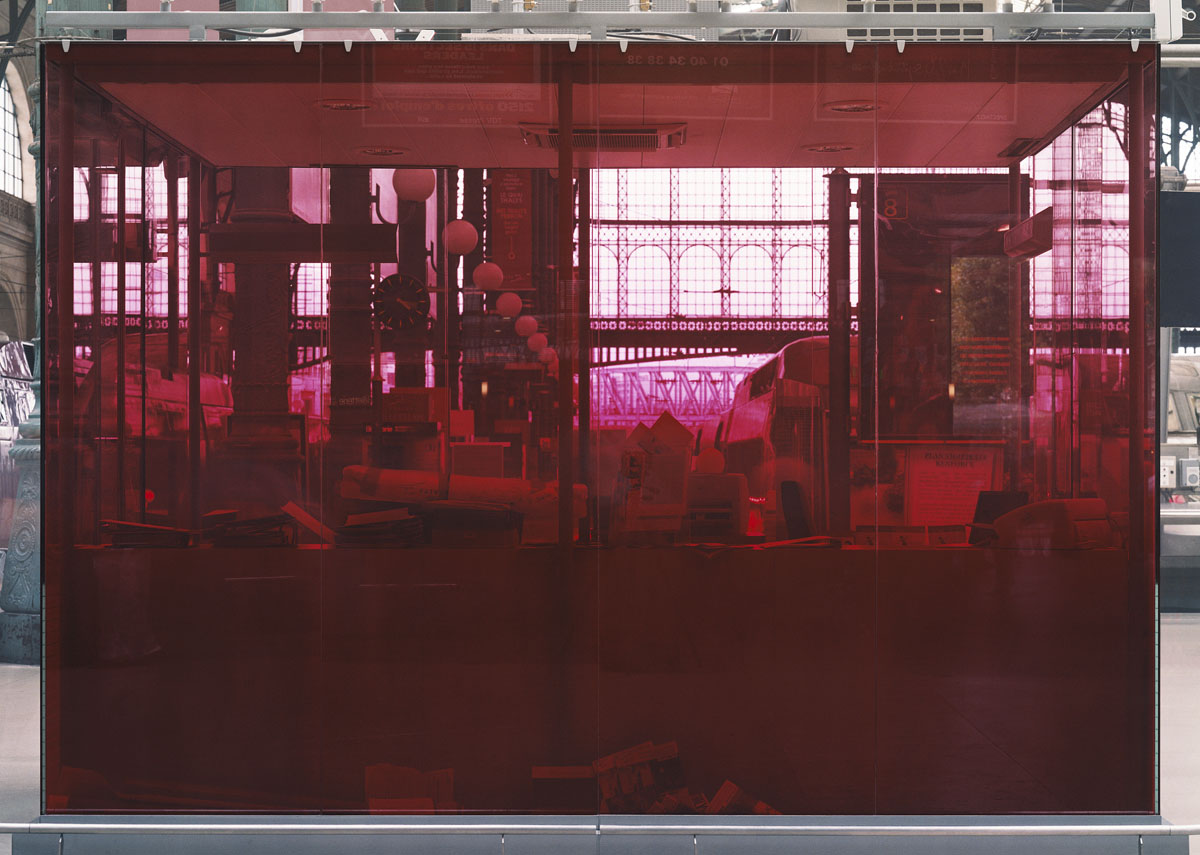

The fourth pattern are walls – glass blocks, blinds, curtains, milk glass, coloured glass – that are pushed up or inserted between the camera and the world outside – often parallel to the picture plane in the camera. As a result, what lies behind, the half- or three-quarter-hidden, appears as though it’s depositing itself, like a fog, like ink on an intermediary pane, as if the pane was a litmus paper that reacts differently to radiation from outside, that obscures the view but at the same time records it. Sometimes with a veritable picture-within-the-picture effect, as in Info, from 2003, or in Building, from 2001. Two pictures overlap here. Sometimes the second one is centred over the first, generating spatial and temporal divergences, along with shifts in perception.

What is conspicuous about this parameter of Van der Salm’s approach is how he doesn’t try to reproduce architecture as three-dimensionally, as dynamic, as volumetric as possible but instead visually reduces, flattens, presses it on purpose; he lets it sink into the lens on the picture plane, so to speak. Instead of 3-D, we find ‘merely’ 2-D volume planes that are brought together and pressed. Put more radically: instead of architecture, image; instead of matter, sign; instead of perspective, surface; and, finally, instead of a physical globe, mountain peaks and houses, we encounter flat map, visual surveys and tinctures, colouring.

There is the wonderful four-part work by Luigi Ghirri titled Atlante (1973), a journey through the atlas, with the atlas, a fictional sojourn along the measurements of the world. In Van der Salm’s work there are matte panes with precipitation, journeys through photographic watercolours, semi-transparent instead of high-contrast, sharpened architectural data. A flowchart on which the data from without is mixed with thoughts from within. In a few of the images he replaces this intermediate plane with blurring. Exterior world and inner world merge then into an undefinable space, leave behind dots, dashes, small surfaces. Or the outside world is connected with a fine net, leaving it unclear whether the net or in “LEDspace” (2019) the LED structure specifies a landscape drawing or punctures it. And in one image it disappears in white, strongly recedes, dissolves into an ‘almost nothing’, leaving a fine bright inkling.

The following images are entirely different. At least as different as individual siblings are from one another. In Spot, from 2000, Van der Salm stepped perhaps twenty to thirty metres back and gazed at a street scene with a high-rise building from a chosen distance. It is night; in the foreground we seen three cars parked on a slightly sloping street. In the background we faintly make out a concrete base with terrace, out of the centre of which the bent body of skyscraper rises. The title Spot probably refers to the dozens of yellowish lights covering the building in a geometric pattern. Judging by the building site and knowing that it is located in Benidorm on Spain’s Costa Blanca, north-east of Alicante, lets us assume it is a hotel. We hardly see the building; instead we are looking at a curtain of light that – in three-quarter profile – rises upwards before us. This round of lights slightly illuminates the base structure of the building. Yet the rendering of what was seen on site recedes, like the building, behind lights, dots, surfaces and stripes of preponderantly yellowish but also white, red, orange, lilac lights. Like the band of a gold watch, like the glitter of a golden handle on a geometrically austere handbag made of bling-bling fabric, the band of light, the field of light extends upwards. We suspect that the reality during the day is probably far less attractive. We only suspect this because Van der Salm depicted the entire scene blurred and thus gave clear preference to the lights. He consequently generated a glow, a ‘mere shining’, a splendour, an almost celebratory glitter that outshines and drowns out everything else.

Nexus, shot in Seattle in 2004, showing the Public Library designed and built by OMA/Rem Koolhaas, functions similarly. The picture appears like the perfection of this form of seeing and photographic rendering. We are gazing by the evening light, at twilight, at a brightly lit showpiece. The sky is settling for the night, the surroundings are already dark black. And in the midst of it all is a small gemstone that despite its size outshines everything, drawing all attention to itself. An odd, strange building that at first resembles the base of pyramids, but ultimately looks like a multiple-cut gemstone that shines out of itself and illuminates the neighbourhood. The brightness of knowledge, the grail of knowledge shines in this image. Again, it is the blurring that gives the splendour of light priority over precisely descriptive, sharp, indexical reality. Together with the lights, the blurriness creates a cool, almost rational sparkle, an aura. A most peculiar sublimity that bears all the power of fright within itself and at the same time has the effect of a contemporary event; a visualization of postmodern knowledge and life and business as it were.

The same building is the template for a quite different image, actually, for two other pictures from 2004 that are very similar to one another. One is titled Prospect and the other Facet. Both photos live from ‘supervision’, from the view from above. Prospect is a nightscape, with all the elements that I’ve described in Spots, with the lights, the shadows. By contrast, the streets surrounding the building glow almost just as brightly. The building is shown from an aerial perspective. Hence, the title Prospect. Like the grounds of Versailles, we see here the city complex of Seattle. Facet, on the other hand, is a daytime image, shot from a lower height, more focused on the library. We see other facets of the building; we see how sharply the building is whetted, for instance, how it is built like a bundle of slanted planes, how it connects enclosing and breaking up building levels.. Van der Salm is working here, and, as we will see later, in his landscapes, with the possibility of shifting, of setting the focal point, and the gradient of the focal plane. He thus pulls the building out from its context, whereas Prospect embeds it. The brilliant, snow white of the cube makes the building shine as if it were carved from a block of ice or out of marble. Display, from 2005, and Square, from 2006, function according to the same method.

In each of these as well as other images, a building is singled out like a gemstone; it is illuminated from within or is surrounded by a wreath of lights and thus highlighted, emphasised. It is presented in the centre as the heart of the picture, but is partially dissolved again by the lighting, turned into a sort of empty space in the image. A totem of radiant light, a field of illuminated dots, an erratic shrine of light in the structure of the city. Multi-perspectivaly cut.

The tool of shifting – a technique mainly used in classic view cameras that allows the tilt shift lens to be moved parallel to the picture plane or to skew the picture plane, hence correcting flying lines – is something Van der Salm uses in his landscapes to direct how we look at the picture, to accentuate a particular building or strip of land that he wishes to highlight. This is quite obvious in the image CH–1995–3, the view from a mountain to the valley below, in which a particular row of houses is emphasised by the sharpness. In Suburb, from 1998; Avenue, from 1999; and Neighbourhood, from 2000; in Expo, 2001; Queue, 2005; Exposure, 2007; Project, 2008, and Landschaft, 2019: in all these images, Van der Salm has set the picture plane at an angle to the lens, creating peculiar zones of sharpness that, contrary to our natural perception, are surrounded by blurred zones not just behind but also in front of them and to the sides. A little like visual tectonic distortions and accentuations.

His attractive, sensuous, at times almost opulent pictorial world (with simultaneous maximum reduction) has its most radical side in images such as Nebula, from 2019, a black-grey cloudy, nebulous wall, photographed straight on; in Zurich, also from 2019, in which the nocturnal landscape dissolves into a sea of light, as if millions of fireflies were flying over the city; in The Fall, from 2018, in which it remains undecidable whether we are looking through a special lens or through a special program at the outside world, or at a long-ago photographed and now peeling image of the world on a wallpaper. Panacea (2015), the frontal depiction of a retail item display; Play (2009), a section of spotted green artificial turf – or the white wall in Costa Blanca (2012), split across six or seven panels on which a hint of a landscape begins to emerge. The elongated red Memo board, from 2006, photographed frontally and precisely, which could be confused with paintings by Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman or Olivier Mosset; quite similarly as well, the red, three-meter-long inside of a corridor, mirroring both sides into one surface, from 2004. Or, lastly, the video Monitor (a photographic experiment), a commissioned work from 2008 for the Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture (Fonds BKVB). Here, he plays back a plethora of images at such a high speed that an intermediate visual realm also appears in the 5.29-minute loop.

And finally, the images of complete blurs in which an even, calm but unpleasantly impenetrable veil, like a perfectly stretched curtain, emerges between us as viewers and what is being looked at, as if a wall of fog was being raised, obscuring the entire outside world, blurring it, making it barely recognizable, and thus placing the blur itself at the centre of viewing. One example here is Levante from 2013.

Van der Salm is, straightaway, known as an architecture photographer. This reputation is supported by his collaboration with various architecture firms, such as OMA/Rem Koolhaas and Herzog & De Meuron. But after these descriptions of his photos, a slightly different silhouette forms on the horizon. He is in no way an ‘architecture photographer’ in the classic sense. That is, he doesn’t photograph in the original sense architecture, streets, houses, and cities. Rather, he turns the thinking around and uses architecture to generate photographic images; he makes ‘photography with architecture’, as I titled this text. He uses, to put it another way, architecture for his pictures. It’s an interesting reversal that is strongly supported by his picture titles. Scarcely any of the titles directly names the architecture or the place where the architecture is located. More often, he names a subject that plays out in the image, a structure, a meaning that emerges in it, such as Plot Ratio, The Pile, Signal, Capital No Capital or Double Standard. How does that work? What is he doing? What exactly does he do? Let’s take a closer look at the two media ‘photography’ and ‘architecture’ and their relationship to one another.

Photography and architecture have an interesting, intriguing relationship. In the history of photography, they have been so closely entwined, indeed intertwined, and sometimes even interdependent that they at first glance appear like twins in spirit, or, somewhat differently, like chicken and egg. At the beginning of photography, architecture was the new medium’s main motif. It stands still there, doesn’t move, doesn’t blink its eyes. Only shifting light conditions change it, subtly, gradually clothing it in a new garment of light. Architecture, with its statics, its calm and serenity, helped the young, somewhat helpless medium photography to get on its feet. The exposure times were so long that for Maxime du Camp only the pyramids and for Louis Daguerre only the built components of the Boulevard du Temple are registered in the image. Everything that was moveable is invisible or heavily blurred.

This initial bonus for photography is something that architecture has in fact retained, at least in the field of view camera photography. To this day, it remains a preferred, highly respected motif. As highly respected as if we were standing before a monument, a tomb, a deity. Hence, nothing should disturb the view of the architecture; hence, the point of view from which the building, the row of houses, the bridge, the neighbourhood, or the interiors is to be set into focus has to be chosen with the utmost care. Shifts will be made so that no crooked, flying lines emerge; filters will be used so light and shadow are perfectly balanced. And the perfect depth of field will be set in advance. The path from the camera position to the subject has been swept clean, the land and air traffic rights for the time of the shot seem to be allocated solely to the camera, the photographer.

Gradually, however, the relationship reversed. At some point, architecture no longer served the purpose of photography. It also sounds less like equal rights and more like an inverted form of dependence, like subservience. Photography began to serve architecture. The classic architecture photographer became a friendly tool whose job it was to follow the architects’ instructions. He photographed the building at the ‘zero hour’—that is, as soon as it was completed, cleaned and made available, thus before it was occupied and assimilated. In this short time span, the building was presented as the architects had imagined it, how they envisioned it, as a lucid structure or powerful icon. A moment of rapture, before the building is put into ‘use’, before it – as Roland Barthes articulated it in Mythologies on the subject of trousers – becomes actual architecture, a functioning building, through use.[1]

Ontologically speaking, architecture and photography are two completely different planets. Architecture is matter and form; photography, by contrast is form without matter. The one is, the other appears, we could say somewhat casually. The opposition couldn’t be more fundamental. And yet in the last two hundred years they have been intimately connected with each other. Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote as early as 1859: ‘There is only one Coliseum or Pantheon; but how many millions of potential negatives have they shed,—representatives of billions of pictures,—since they were erected! Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble ourselves with the core.’[2] As early as 1859 there were apparently millions of negatives of the Colosseum and the Pantheon, as the basis for billions of pictures. How many more are there today, printed, and even more hurtling around the globe in digital form, in the media age, in the age of simulation, as Jean Baudrillard put it, in the society of ‘simulation modernity’. Formulated in the 1980s, Baudrillard’s theory regards society as entirely saturated, interwoven, determined by the media: ‘Everywhere socialization is measured by the exposure to media messages. Whoever is underexposed to media is desocialized or virtually asocial’.[3] And tapered in the succinct words of Michael Wetzel:

The world becomes an occasion for its photographic and filmic reproduction, and the images from all over the world replace the world view. We could say: being an image takes ontological precedence over being. New media and computer technologies have catapulted us into a zone of indifference toward being and appearance. The world of simulacra absorbs the appearance and liquidates the real.[4]

Nearly all architectural photography – when it isn’t openly or covertly social photography – shows architecture in a state of perfection, in the form of a (still) empty concretion, without people, without use, as the purest possible visual realization of a particular, personal, idealised notion. The control on the part of the architects is therefore so strong because they are keenly aware that images speak a language of their own, that they stimulate other discourses than the physical experience of architecture, because they sense how photography transforms volumes into surface, distils matter into form and signs, how they can change architecture, accentuate it, enlarging, reducing, deforming it in the picture and then in our heads. That also means either elevating it into a promising brand or degrading it to a joke, debasing it. And since things are no longer built ‘for eternity’ – commercial constraints prevent that – the chances increase that the picture will outlive the body, and photography architecture. The world’s famous buildings already circle the globe a thousand times as a picture before we actually experience them in reality, before we ‘feel’ them, ‘smell’ them as a building.

Architecture helped photography to take shape, to develop its qualities, to grasp the picture plane and picture depth as a system, as a pictorial play. Now photography is helping architecture to also be successful in a mediatised world. And to be successful in today’s world means fifty percent content, fifty percent communication. Or sometimes, as we know, a ratio of 10:90 is sufficient. At the latest then, architecture photography will be paid very well.

Van der Salm’s work has a good deal to do with that and at the same time very little. Yes, he shows architecture. Yes, he works with it. It is his motif, his subject. But he is not architecture’s helpmate. He engages halfway with the classic pairing of photography and architecture; he deals with the themes of matter and form, construction and façade, but his main interest is the picture, the construction of an image, the transformation of reality into a picture, firm matter into fluid spirit and light, cement into thoughts. In a fascinating way, his work refers to the beginning of the relationship between photography and architecture. Architecture is his model, prospectus. He, too, often works with long exposures and blurring, but not because his lens and data medium, like in earlier times, are not yet that sharp and brilliant and the shutter speeds are not yet that short, but because they correspond to his artistic intention. His central theme is the perception of the world, the perception of the real and concrete, the firm and the fleeting, the factual matter and its enchanting or vanishing light. Linked with the many questions about how we perceive, what we see, what we block out, what is reflected on the photographic picture plane, what gains a foothold and in which form it etches itself into our brain, is how we – actively or passively – transform it into an intuition, into knowledge, into spirit.

Van der Salm creates images of perception; with his pictures he addresses the theme of perception, and with his perception the image. And that is something he visualises on and by means of the built (or to be built) object ‘architecture’ and by means of the optical tool of photography. We could simply paint a nude person, or something wilder, more daring, to think along the painted nude about the nudity, the existence of humans in the universe. Van der Salm mainly does the latter. He makes photographs with architecture that reflect on perception, on inside and outside, subject and content, subject and order in our existence.

Does he also make architecture with photography? I don’t know. That would need to be considered separately. At any rate, however, his photographic work reveals many levels of meaning about building, thinking and perception – the elements with which we structure our existence on earth.

[1] Roland Barthes, Mythen des Alltags/Sprach der ModeMythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013), p.

[2] Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Age of Photography,” The Atlantic 3, no. 20 (June 1859), pp. 738–48, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideastour/technology/holmes-full.html, accessed 24 Sept. 2020.

[3] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations (Ann Arbor: UMP, 2002), p. 80.

[4] Michael Wetzel, ‘Paradoxe Intervention: Jean Baudrillard und Paul Virilio: Zwei Apokalyptiker der neuen Medien’, in Simulation und Verführung, ed. Ralf Bohn and Dieter Fuder (Munich: Fink, 1994), p. 97.