We jog through the dark wood; it gives my partner the creeps. We stand on the bridge and admire the force of the water; the children are afraid and turn back towards the safety of the land. We gaze, awe-struck, into the depths of the sea, while beside us a sailor whistles a love song. The light goes out suddenly in the underground parking garage, and we fumble fearfully for a switch. We move apprehensively through the rocky caves while our companion talks incessantly about the beauty of the stalagmites and stalactites. We look down, shuddering, into the gorge, while above us a hang-glider circles. We see our father on his deathbed; is he only asleep, or is he dead? We dream of going for a walk, and suddenly we hear footsteps right behind us, swivel round and see – ourselves. Uncanny: – we awaken with a start.

"It is part of what we regard as awful, dreadful and terrifying", says Freud in his essay on "The Uncanny"1. But something that one person regards as uncanny may not be considered uncanny by someone else. Things and experiences are varyingly uncanny to different people at different times, and the word in itself is not so alarming. It is, says Freud "not always used in a sharply defined sense, and it is usually associated with the cause of the fear it engenders."2

Freud looked for the special quality that justifies the use of the word and found the following in the discussion on the paper by E. Jentsch "The Psychology of the Uncanny" (1906): the German word "unheimlich" (un-homely, uncanny) is the direct opposite of "heimlich" (homely, familiar, harmless); thus it follows that everything that is unfamiliar and unknown, everything with which we cannot feel "at home" – or "heimisch" – must be alarming. Unfortunately, however, although new and unfamiliar things may have aspects that really are uncanny, this is by no means always the case. So Freud continued his search for explanations in languages other than his native German and found a whole series of English words, apart from "uncanny", which have a bearing on the German "unheimlich": uncomfortable, uneasy, gloomy, dismal, uncanny, ghastly – and there are many more. But this did not help him with his definition. In fact, his investigation of the word "heimlich" is more interesting since it has two completely different meanings, namely "familiar", "known", and the other meaning of "secret", "hidden". Freud found a remarkable statement by R. Gutzkow: "What do you mean by 'heimlich?'" "Well... I think both you and I regard it rather like a dried up spring or a dried up pond. You can't walk on it without thinking that water might appear at any moment. We call that 'un-heimlich' (uncanny), you call it 'heimlich' (familiar, but also hidden)."3 And he added an extract from Schelling: "We call everything uncanny which should remain hidden and secret ... and which has come to light"4.

Amazing, this ambiguity which is so extreme that the word has two, almost opposite meanings. The German Dictionary written by the Grimm Brothers of fairy-tale fame explains it as follows: "4. from "heimatlichen, häuslichen" (homely, familiar), that which is concealed from alien eyes, hidden, secret... 9. the concept of hidden, dangerous which is part of "heimlich" develops further and acquires the sense of unheimlich".5 Freud goes on to try and prove that this development of the semantic field suggests that the feeling of anxiety, defined as unheimlich (uncanny), is a "recurring repression"6 and, according to Schelling, something hidden that should have remained secret but which has come to light, something that was once familiar and homely which has now become "unheimlich" (uncanny).

Freud illustrated this by some examples of situations that can evoke the feelings which make us regard something as uncanny 1. Uncertainty about whether a supposedly living being is really alive and, vice versa, uncertainty about whether an inanimate object, such as a doll or a machine, is really an animate being. 2. Anxiety about eyesight. The fear of losing one's eyesight – so terrifyingly described in E.T.A. Hoffmann's story "The Sandman": "There is a wicked man who visits children when they refuse to go to bed and throws a handful of sand in their eyes and makes them pop out of their heads. Then he thrusts them into a sack and carries them off to his own children who are sitting in a nest with curved beaks like owls which they use for pecking out the eyes of naughty children."7 3. The phenomenon of the doppelgänger, or double, i.e. "the appearance of persons who are held to be identical with other persons owing to fact that they resemble them", the transfer of spiritual and mental processes from one person to another, excessive identification with another person, "so that one becomes uncertain of one's own ego or replaces it with that of an alien ego, resulting in the doubling, division or exchange of the ego – and finally the return of the same."8

The uncanny, says Freud, feeds on the omnipotence of thoughts and wishes, magic and sorcery, our relationship with death, the revival of the inanimate, unintentional, unforeseen repetition or behaviour and the castration complex, and we experience things or situations as uncanny either through the reactivation of repressed infantile complexes or through the seeming confirmation of past primitive convictions.

The potential of the uncanny is exploited in literature, films and the visual arts. It is used in horror films merely to provide the spectator with the fright for which he has paid, in the more demanding context of plays, stories, paintings and sculptures to evoke a usually subliminally inherent (surrealistic) change between reality and fiction and fantasies and back again – a process which is often responsible for an uncanny feeling in works of art – for the powerful portrayal of concrete events or of intrinsic elements in earthly existence. The uncanny is a means of escalating emotional readiness, of getting across a meaning or of cutting down to essentials. It is also a frequent means, used by surrealism too, of referring to the hidden or repressed, and to the thin dividing line between this conscious, rational understanding and the purely animal.

It is a noticeable fact that the potential of the uncanny is currently being used more often and more forcefully, not so much in an attempt to keep pace with the attractiveness and predominance of the entertainment industry – which, incidentally, evokes the uncanny omnipresently as a sales incentive (why does it sell so brilliantly these days?) – as with the aim of addressing the great social and intellectual uncertainties of the waning 20th century. (Do we know what we should be eating, how to interact with each other, how to keep our jobs, how to react to the new technologies, how to have a positive influence on the changing climate, how to avoid going crazy – have we one single reliable answer to these and a hundred more questions, an answer that will bring an element of stability into our existence, reassure us and endow us with the ability to act? In fact, the answer is the only straightforward thing about the whole uncanny situation – and laughing about it the only liberation.)

The photographs by Vanessa Beecroft, Dana Hoey, Anna Gaskell, Natacha Lesueur and Wendy McMurdo, as different as they are – and this difference is the subject of the following discussion – all evidence a strong potential for "the uncanny". Take the theme of the doppelgänger, for example, which appears in the work of Wendy McMurdo, in Anna Gaskell's portrayal of Alice as her own double in the group of photographs referring to "Alice in Wonderland", in Dana Hoey's strange, eerie double formations, and in the repetitions and multiplications of Vanessa Beecroft's tableaux vivants. Or the theme of injury in Natacha Lesueur's physical impressions, of concealed and open violence in Dana Hoey's scenes of everyday life, and of subliminal power in Vanessa Beecroft's performances. Or the objectivisation of living things in Beecroft's artificial, doll- and statue-like female figures, in Lesueur's sculptural aspic heads, and in McMurdo's portraits of defunctionalised gestures (music-making without instruments, using a computer with no computer). And finally, the classical theme of the displacement of proportions and the elimination of perspective in Anna Gaskell's groups of photographs entitled "wonder" and "override", which refer (the former directly and the latter indirectly) to Lewis Carrol's "Alice in Wonderland“ and "Alice through the Looking Glass".

In fact, however, these works do far more. For her photographs on the theme of the doppelgänger – which was formerly seen in a much more positive light as a way of stealing a march on death (perhaps the concept of the immortal soul is an early form of the phenomenon of the doppelgänger, conjectures Freud) and is nowadays regarded as threatening since it throws doubt on uniqueness, on identity – Wendy McMurdo uses children in theatrical situations. A bare, sober, severe, almost empty stage, simple theatre lighting, the events in the foreground pointed up; a few properties – a bench, a table, four chairs, a few straws – are sufficient to evoke a barely realistic world in artificial surroundings. The reflective, almost old-fashioned framework and the reference to 19th century portraits are contrasted by the use of modern photographic technology: McMurdo clones the children, confronts them with themselves as someone else – oh, hello, who are you? -, places them at right angles to each other, in profile and frontal at one and the same time, sitting on a bench and confronting or restraining their other selves with apparent familiarity. McMurdo works with multiple perspectives and identities, stretching space and time and transforming them into the image of a no longer tangibly and sensuously perceptible world.

The lightness which characterises the children's facial expressions and the openly experimental scenario – there are stacked-up chairs in the background, we are backstage as well as on-stage – undermine the gravity of the situation in which it is no longer possible to decide what is real (are they really twins?), what is going on, whether the scene is completely artificial, whether the photo is "real" or manipulated, which of the two persons is the original and which the vis-à-vis – all conjectures which, remembered elements of a dream or a "traumatising" encounter, trigger huge fears about our own identity.

This schism between the real and the virtual world assumes a particular clarity in the pictures with children sitting in strangely rigid, almost sculptural poses in an empty room, apparently operating a non-existent computer. The black box which conjures up digital, virtual space has been digitally removed, leaving the children alone, poised as if to fall into an empty space which we cannot see from our outside position and a time which we cannot experience, in our midst and yet absent – and alarming despite the thoroughly contemporary charm of the children.

The recent work of Natacha Lesueur, on the other hand, is dedicated to a kind of elaborate craftsmanship that results in photographs of a strange artificiality: female busts photographed from behind, bedecked with smooth, shiny headgear made of cold cuts of meat, spaghetti, cucumbers, maize or cauliflower, all ingeniously and ornamentally enveloped in aspic. The headgear resembles a strange bathing cap, colourfully and formally ornamental on one side, abstract or slightly figurative, sometimes reminiscent of the convolutions of the brain, and on the other side irritatingly confusing because it is made of food. The displacement of edible substances from more normal situations to the head disturbs our perceptive processes, triggers surprise – and perhaps disgust.

Natacha Lesueur started playing with elements of provocation and confusion in her very first large group of works. We see bodies and parts of bodies of women – a knee, a neck, buttocks, legs – on which ornamental shapes have been incised. Rather like the impressions left on the skin by socks and underclothing, these female bodies are ornamented by deep impressions like beautiful jewellery – and at the same time like colourless tattoos which suggest an invasive process.

Then a facial network of caviar, pig-gut stockings, broccoli purée as body cream, a fish-skin chignon, a hair-flower made of decorative raw ham "petals" – in Ingres-like portraits and with an Archimboldo effect – or the headgear of food in aspic: combinations of photographed food and body art in which beauty and horror go hand in hand, a balancing act between surface and depth, fashion and invasive intrusion, ornamentation and torment. An act of incision in a time of non-tactile virtual communication, a kind of "incarnation" of physical and non-physical stamps, of simulacra.

In addition to her film "floater" (1997) and her drawings, Anna Gaskell's photographic work consists of three large series, "wonder" (1996), "override" (1997) and "hide" (1999). The first two of these series are included in this exhibition, and the recently completed "hide" is currently on display at a solo exhibition in London. Of all the work shown here, it is these three series with their surrealist displacement techniques and David Lynch-like tensions that are probably most typically concerned with "the uncanny". "wonder" refers directly to Lewis Carroll's "Alice in Wonderland" and "Alice through the Looking Glass". We encounter Alice in the pool of her tears, her fall down the rabbit-hole, her changes in size, her experience of being two people. We gaze into her face without being sure whether she is laughing or screaming in an act of self-mutilation, we observe two figures and cannot be quite certain whether one of them is trying to revive or kill the other. A magical, wild and wondrously cruel series with fine, full colours, swathing us agreeably in noble, old-world blue mixed with warm yellow before thrusting us all the more abruptly into the next displacement. Anna Gaskell achieves this shifting from small to big, from real to fictitious, from harmless to threatening with a "free" camera which jumps from a bird's eye to a worm's eye view, which shortens and dynamises lines, mixes "meadow world" angles with condescending adult views of children from above, and which uses different depths of field and angles of light to guide and beguile our eye, charging "innocent" children's legs with sexuality and propelling them into the ambiguity of seducer and victim.

"override" adopts the ductus of the first series in cooler, more modern colours, with four children scrapping and playing. But the photographs have something disturbing about them. We cannot be sure what we are actually looking at, whether these are "normal" children's games or something far more violent. Hair is pulled, tugged or torn, there is a child lying on – thrown to? – the floor, tied up or shackled. The camera angle explodes the intact world of the child, shattering bodies into fragments and creating a projection surface readily receptive to an aura of eroticism. Like a probe capable of penetrating the body, the camera intrudes into the child's world, illuminating it from within and changing everything that looks harmless and intact from a safe distance into an unknown, uncanny scenery. Children as fairies and monsters at one and the same time? Or is this a metaphor for a world that is both fantastic and monstrous, where the barrier blocking the road to devastation is very thin?

Dana Hoey begins with threatening photographs of ostensibly everyday situations: an encounter between a young woman and two aggressive-looking women outside a toilet; a woman nailing another women to the floor; a woman (a mother?) pushing a (her?) gagged and shackled child into a car: images suggesting conflict, a potential for violence and drama portrayed with a good deal of clarity. The more recent photographs are more ambiguous. The photographer plays with the thin borderline that separates everyday normality and horror, showing women in ostensibly normal activities – on the beach, walking with a dog, in a wood, in light-flooded undergrowth, at breakfast, gathering flowers in a garden, outside a whitewashed villa or talking on the street – an apparently normal, intact world with disturbing intimations of doom: the fixed stare of a dog, a huge coffee stain on a white T-shirt, the gesture of a blow. We seldom see anything definite, we cannot be sure what is going on, but there is a sense of foreboding that permeates the visible and changes the "heimlich" into the "unheimlich". Even the images expressing kindness and readiness to help, like that of two women trying to help a third to cross a river, take on a threatening aspect in the context of the other photographs.

Remarkable, particularly from an American feminist angle, is the fact that Dana Hoey puts women into mutually threatening physical situations which were hitherto the male domain.9 Both Hoey and Gaskell tear open the intact world of sisterhood and reveal it is far more complex than might be supposed, exposing "coziness and cameraderie" as a masquerade10 without explaining where the potential for violence comes from. Both artists relate "from within" rather than observing from the outside, at the same time turning the "victim-perpetrator" role in on itself.

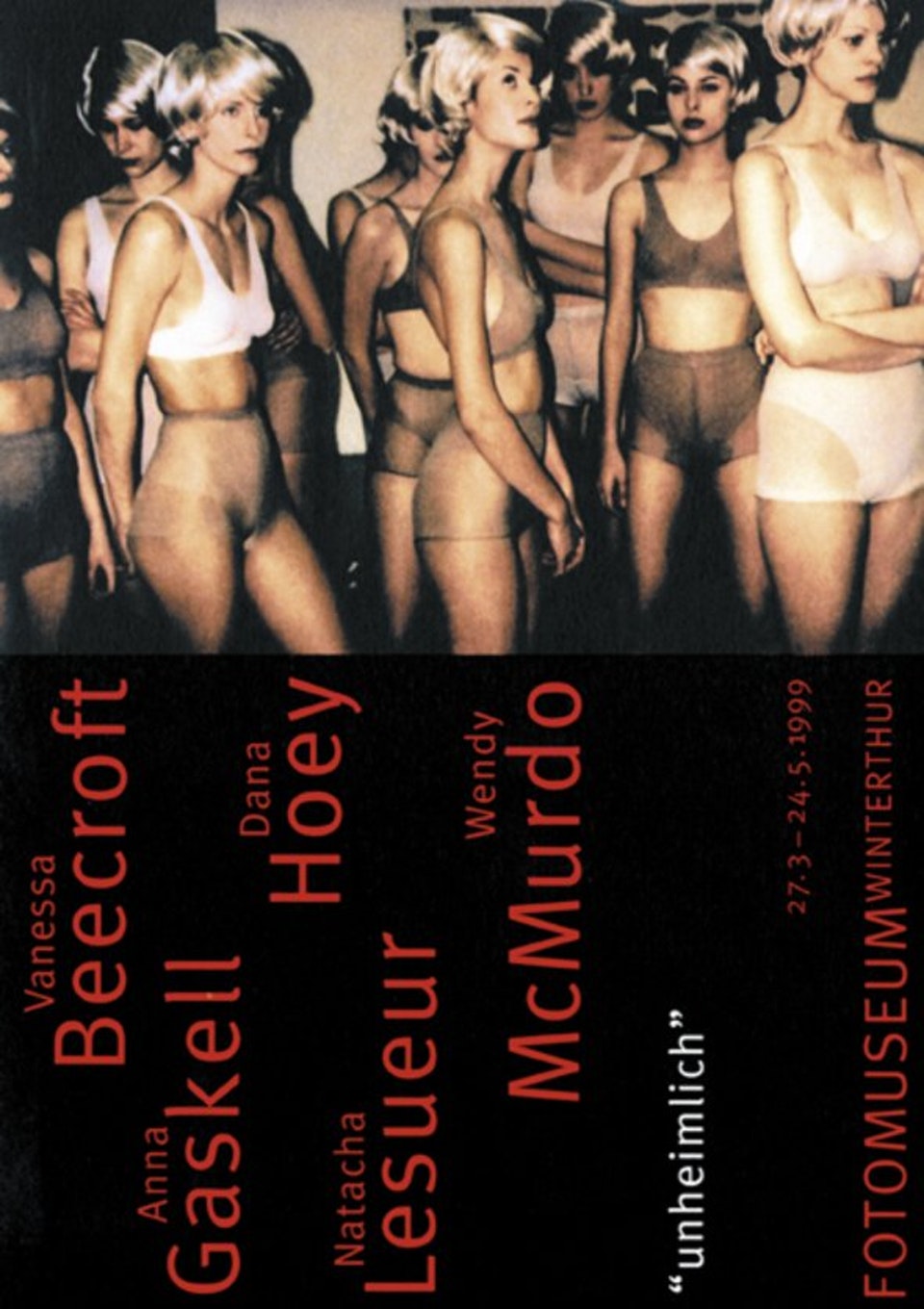

Following Dana Hoey and Anna Gaskell, Vanesssa Beecroft's performances, which she sometimes calls "shows", have the clear intention of putting women on show. Using first herself, then friends, then women from the street, most of them now professional models, she undresses a group of women, and re-dresses them in new and identical clothes, with minimal coverage but well designed, and places them in artificial surroundings in front of an audience. There are allusions to the old tableaux vivants and to contemporary catwalk or rehearsal situations, as well as reminiscences of harems and military formations. A crazy, disquieting mixture, reinforced and enhanced by the meagre clothing – bikinis, nylons, bras and wigs, a shirt with nothing below the waist, a naked woman wearing an army cap, and always very high-heeled shoes or sandals – which allude to, frame and emphasise the women's nakedness.

The situation, a fertile field for eroticism and sex, is in fact extremely cold, even objectivised. The women are all dressed the same (sometimes juxtaposed with two different-looking outsiders wearing different wigs), almost as if they were in uniform. They stand there for hours on end, hardly moving, sometimes relaxing by crouching or lying down, but most of the time standing like statues, like frozen sculptures in space, on pedestals (high-heeled shoes), waiting. No, not waiting – they are simply there, for a specific time. Like alien beings, like display dummies, staring with a clear if somewhat bored gaze through the spectators – the males ones too – into the distance, as if the audience were not there, as if they were from another world with no interface with the one shown.

Vanessa Beecroft works with alienation and ambiguity, doubling and multiplying. She clones her models, emphasising their model- and object-like quality, the mixture between beauty and intangibility; they make an alien, almost extra-terrestrial impression, devoid of any narrative or theatrical connotations. Devoid, too, of "sense" in its conventional meaning, suffused with a strange "disinterested", indifferent emptiness suspended between passive and aggressive states of tension. A disquieting laboratory situation of great aesthetic fascination and social foreboding. What is going on? Who are these women? What do they want? Who is watching and who is being watched? Who am I, in this context? Identity is called sharply into question.

The keyword of all this work is ambiguity, a state of transition which conveys no safety, a state of floating, drifting. At times it is pleasurable, at times uncanny. Nor can we avoid it, however hard we try to hide. Nowadays, the uncanny is no longer manifested in deep, dark forests as it is in fairy tales, it is around every corner of everyday life, it is beside us, in us, in our anxious uncertainty about our bodies and our thoughts, in the uncertainty of our encounter with a rapidly and dramatically changing world. Uncanny, this critical-philosophical perception of inner and outer states.

Yet the ambiguity inherent in the theme has furnished a fertile soil for fascinating, beguiling photographs, photographs with a pictorial quality, with references to painting and Victorian photography (Wendy McMurdo), to literature and films (Anna Gaskell), to soap operas, to the "family snapshot" (Dana Hoey), and to tableaux vivants (Vanessa Beecroft). These are pictures of uncanny beauty, uncanny familiarity and uncanny everydayness.

1 Sigmund Freud: Das Unheimliche (1919), in S. Freud, Psychologische Schriften, vol. IV, Frankfurt a.M., 1970, here in translation by Maureen Oberli-Turner. The page numbers refer to the German original.

2 S. Freud, ibidem, p. 243

3 S. Freud, ibidem, p. 247

4 S. Freud, ibidem, p. 248

5 S. Freud, ibidem, p. 249/250

6 S. Freud, ibidem, p. 263

7 S. Freud, ibidem, p. 251

8 S. Freud, ibidem, p. 257

9 See also Alexander Alberro: Dana Hoey, in: Artforum, January 1998,

p. 103-104

10 Felicia Feaster, in: Art Papers, January/February 1998, p. 54