Frozen Life

An extending gray field is rippled by waves, ranging from charcoal gray to dark gray to slightly brighter hues. Within this field there is a maze of lines, open and closed contours. They look like scratches on dark stone; like the white edges of an evaporated drop of water; like chalked marks; like the superimposition of many swiftly drawn bright signs. The lines are wavy, scribbled, and informal. Rarely do they add up to a shape that seems to be a figure, the sketchy outline of an animal, say, or a face reminiscent of pre-historical wall paintings. This association is sustained by a feeling of spatial-temporal depth that besets the viewer—it all seems far away or as if it were seen from afar. Am I looking at the vault of a heaven just about to crystallize? At the evaporations of some strange material? A blackboard full of traces of incomprehensible signs? A mound of broken glass after an explosion? Is this what the fallout from the implosion of the digital universe that I fathom through my computer screen will look like? Or am I just looking at an opaque, milky surface that merely simulates depth? The all-over structure of the image, the effaced perspective, and the lack of any point of reference make it impossible for the viewer to decide whether he is looking at minute details, a microcosm, or at gigantic lineaments up in the sky, a macrocosm. Depending on the angle of light, the viewer delves into the darkness of the lower layers and is sucked into their depths, or his gaze dances on the surface, on a grid above a deep dark hollow.

Once there was a man who had a hollow tooth. In this hollow tooth, there was a little box. In this little box, there was a note that said: Once there was a man who had a hollow tooth. In this hollow tooth, there was a little box. In this little box, there was a note that said: …This Swiss doggerel aptly illustrates the feeling of looking at this picture. You get the impression that every shape, every field repeats the whole, the small the large, the large the small, no matter where and how deep you look.

This is not the only picture. There’s a second one, a third, fourth, fifth one, sometimes even a ninth or tenth picture. A series of large pictures evolves, rhythmically hung across an entire wall. In each of the pictures in the series in front of me, a strange indented oval shape appears, reminiscent of an egg pierced by a spermatozoa. It is repeated, but every time it is seen in another place and from another angle, as if someone were pac- ing up and down in front of a portal whose Kafkaesque doorkeeper will not let him in. It is as if your gaze, nervously looking for a structure, were circling around an absent focal point. The pictures seem to show the same environment, yet each view is slightly shifted, photographed from a slightly tilted angle, as if they mapped a field; as if they circled around a situation; as if they were searching for something.

This circling, searching motion in the sequence deserves a closer look, as it occurs in the absence, or at least in radical reduction, of a classical order of perspective. Hans Danuser photographically charts an “area” less systematically than a land surveyor would, but does it with a much more closely scrutinizing gaze. He looks at it as if it were the site of a crime, as if it put a vertiginous spell on him. Danuser is a cartographer gone slightly astray, with an open eye, without a clearly defined purpose. His movements seem to be dominated by uncertainty, and perhaps restlessness. There is no order, clarity, or certainty. There is hardly ever anything that would offer hold or that could serve as a scale. The gaze seems to precipitate across a fabric of bright lines, ever deeper, endlessly. Does the photographer “describe,” “delimit” a boundary? Does he visualize the transition from a known systematic order to a new open field?

Other series of images from this group of works seem more three-dimensional. They read like images of crumbling rocks, splitting slate, or sprawling mycelium. The outlines are filled out; they become fields that break off and pass onto other levels. There are outlines that even seem to have volume like a relief map. Finally, the viewer starts to realize that these are photographs of ice, of water at various degrees of frost, ranging from a few degrees below freezing point to zero degrees Fahrenheit. The colder the ice, the brighter the images seem, until they almost become a glittering glacial sky. The warmer the ice, the darker the background against which the signs brightly stand out. Temperature also changes the crystalline structure of ice from softly curved to sharply rectangular. These pictures are called Frozen Embryo Series. We could also call them “frozen life.” But we cannot discover a single fetus, even if we look extremely carefully. The title refers to the history of these images, so to speak. In the early 1990s, Hans Danuser began photographing in research labs where fetuses were used to test the effects of new drugs. These labs also performed prenatal medical and surgical operations, and created access to stem cells and the genetic code. In a series of works resulting from this investigation, Danuser placed a fetus, surrounded by a luminous circle, in the center of each photograph, as if some scientific aura illuminated the fetus. Over the years, he has created new works in the same area of research, forgoing this “striking” motif and concentrating solely on the ice. The eye does not look up to a sky; it rather stares at tubs filled with ice, which serve as the material basis, as the foundation for experiments and case studies. The ice crystals that freeze life in order to place it at science’s disposal do not mirror heavenly light, just simple lab lights. “The paler the light, the more silent, more unfathomable, and the more soulless becomes the sector in which the photographer delves ever more deeply like a deep-sea diver.” (Juri Steiner) But the manipulations of the genetic code that are being performed here are creative, “heavenly,” at least in regard to their potency and their power.

Strangled Body

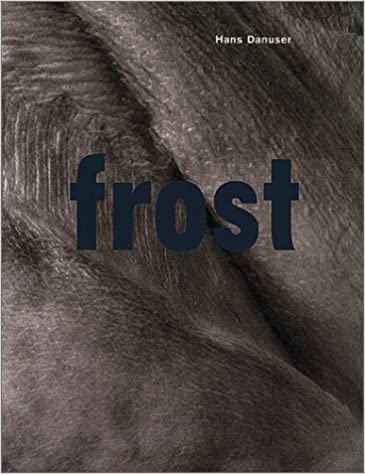

In Strangled Body we once again encounter this incredible gray. It’s an almost seductive range, a delicate differentiation of hues. They are condensed into an increasingly darker gray; they coagulate to a deep black; they get denser and start to overlap. Then they are drawn out again, extended, diluted, like stretched skin, and the same amount of color seems to be dispersed across a larger field. We cannot make out any contours. Everything seems to be in transition, a smooth transformation from the brightest hue, a medium gray, to the deepest and darkest shades. Color draws the gaze across seemingly transparent skin into an abyss. Color consumes the gaze and lures it into the darkness. You instinctively draw back from this abyss. What gravity! What repulsion and attraction! The heaviness of the colors, weighing on our eyes like lead, stands in disturbing contrast to the soft shapes. According to our experience, this kind of heaviness is otherwise geometric, cubic, heavy metal. Whence this combination of soft shapes, reminiscent of skin, of vesicles, or of a body, with this sensation of weight? Are these colliding huge, soft planets? Are we staring into volcanic faults? The almost monumental enlargement of the bruises on strangled bodies shown in the photographs effaces any sense of scale and any reference to reality—the indexical nature of photography, as it is called in theory. It transforms the depictions of injuries, of strangled and mutilated bodies into images of horror, of a chasm, of an abyss. The images reduce the tangible; they fragment it and transfigure it into an abstraction of torture’s night and of power’s performance. The series that Danuser showed at the Kunsthaus Zurich in 1996 consisted of alternating upright and oblong photographs, four each, that formed a kind of chain enclosing the viewer who beheld himself mirrored in the glass and confronted with these more than life-size voids of violence. The new series, Strangled Body (2000), seems calmer; I am even tempted to say, more balanced. The pictures are no longer rectangular and outsized. Their size is an energizing almost cubic 59 x 55” format, one of Danuser’s favourites. The gashes are smaller this time; they look like marks on an almost furry epidermis that even seems sensual and erotic at times. The drama is strongly diminished. The atmosphere seems more factual and stoic, but also more ambiguous.

The Frozen Embryo Series deals with the study of the prenatal body, whereas the Strangled Body photographs investigate the forensic examination of the body post mortem, after lethal torture or suicide. Before birth and after life, in a violent death: heaven and hell. Both work groups, even though a life’s span separates them, are united by subject matter and several issues they address. Both series focus on “man,” the unborn and the dead human body, the very limits of human life. They investigate the twilight zones of our knowledge about ourselves. In both instances, Hans Danuser enters areas of research that are off-limits to the public, forbidden zones. The core issue intertwining these works is the concept of power—on the one hand, the power of knowledge, of intervention, and of healing, the ethical challenges genetic technology has had to face during the past decade; on the other hand, the power to kill, to eradicate life. In both cases, we encounter a powerful use of force, a violent relation to the vulnerable human body. One—the prenatal—is more hidden, the other is more obvious, and the intentions are diametrically opposed.

Erosion and Sedimentation

Once again an array of hues of gray. This time it’s mid-range gray that never sways toward dark gray, black, or white. Subtle differences within a small range indicating that something is falling apart, dissolving, flowing away—continuously, bit by bit, and sometimes there’s even a landslide, when whole parts break off, fall apart. Danuser shows eroding soil. He has explained that eroding slate sand in the mountains of Grisons, Switzerland was the starting point of these images. There is the natural sedimentation of mud, of slush, an eternal, seemingly useless flow from the mountains down to the valley, from the valley to the sea, to the immense delta. Or erosion can be engineered and used by humans to gain land, to conquer the river and its sprawling, ever expanding meanders, as people have been doing in the Swiss region of Hinterrhein for more than a hundred years, a hydrotechnical long-term project.

Slate sand is gray, almost incredibly gray-gray. Hans Danuser’s photographs of slate sand are gray. A kind of one-to-one color image. The black-and-white of Hans Danuser’s photographs is a realm of infinite hues of grays—his Hell-Dunkel (bright-dark), as he calls it. And here, for once, the colors are real. Black-and-white photography, usually an abstraction from the real riches of color, unexpectedly acquires a naturalist quality. But Danuser’s gray world always has its very own specialties. The sum of all colors of the spectrum is gray. Gray, in contrast to black and white, is not an absence of colors, but rather their sum. It is not created by subtracting, but by adding color. Danuser’s hues of gray vitally depend on this. His own, self-created range of bright and dark seems as rich as a range of colors would. It’s a saturated gray. The structure of the image is equally complex. Danuser cuts out fragments of reality in a manner so radical that we lose any sense of scale. The fragment detached from its context is an abstraction of the thing and its place in the system of photographic perspective. But this detachment permits Danuser to concentrate on a meticulous scrutiny of dense fields of color. It enables him to focus on an open field requiring a kind of floating, open-ended perception. In the sum of the reductive single images something abstract becomes visible—a topic, a state, a relation.

The ground under our feet moves. Permafrost thaws. Even rocks erode, are carried away, first as large bulky boulders, then as little round pebbles, and finally as sand. Erosion shows this eternal and ever new natural cycle that dissolves even seemingly solid, secure, and immovable objects. Danuser conveys this feeling in exhibitions by showing the photographs as floor prints that we can very carefully walk on. As in the Frozen Embryo Series and Strangled Body, the focus is on power, a play of forces, in this case slow erosion and sudden landslides. Man can control and harness these forces if he approaches them carefully. But he is helplessly exposed to them once the mountain starts to uncontrollably slide. Heavy rainfalls drench the ground until a critical saturation is reached and the mountain starts to move. Erosion II visualizes these forces in images of suffocating slush that seems to dry like mortar and rock-solidly buries everything beneath it. Hans Danuser’s work on the natural forces of erosion acquires social dimension in the context of the contemporary global economy and society; we can read it as a symbol of a society eroding at every corner.

The Eighties

Danuser began work on the three series discussed above in the early 1990s, during the same period he worked on the first images of frozen life. Together with several site-specific commissioned works and a few “landscapes,” they mark a distinctive period of Danuser’s work after the publication of In Vivo in the late 1980s. In Vivo showed 93 photographs, grouped in seven chapters. In Frozen Embryo Series, Strangled Body, and Erosion, he continued to pursue the issues and the visual discourse he outlined in In Vivo, a retrospectively almost prophetic book. In the 1980s, fashionably unshaven yuppies with padded shoulders caroused about as if humanity, or at least the West, no longer had to shoulder the burden of history. They excessively and licentiously celebrated the cult of the individual, as if man had been liberated from existential worries, the shackles of outdated value systems, and the repressive sense of social responsibility. In this climate of greed and gluttony, In Vivo pointed to the twilight zones of civilization where our present and our future will be determined. In this long-term project, which consisted of several series, Hans Danuser dared to venture into the most decisive and ethically most contentious areas of our thinking, calculating, acting, and profit making. He identified seven neuralgic spots in economy, science, research, and technology as starting points for his photographic inquiry: Gold, Atomic Energy, Medicine l, Medicine ll, Physics l, Chemistry l, Chemistry ll are the titles of the chapters. Each of them addressed another dilemma of our civilization.

In Gold, the process of refining gold is represented in alchemistic, almost symbolist images as the greedy quest for surplus value, the Holy Grail of modernity. Looking back, the series seems like a secular version of the expulsion from paradise. The separation of object and value as expressed in gold or money parallels the separation of consciousness and being. It brought about an abstract world where capital allows for swift movements, but also reigns supreme. As Peter Sloterdijk writes, “Money is abstraction. No matter what values are at stake, business will be business. Money does not care about anything. It is the medium that, for all practical purposes, levels any difference.” The photographs of gold bars from England, France, and the Soviet Union loom like commandments written in stone, like icons of the old world order that eventually ended in 1989.

The Atomic Energy series densely and darkly illustrates the quantum leap that nuclear technology represents to humanity. Man has passed a threshold vesting him with a power that allows him, biblically speaking, to move mountains. The series is divided into two parts. The first part leads us from the outside to the inside, through the billowing steam of the cooling tower and along precise and harshly lit corridors to the “controlled” nuclear fission. The second part primarily shows storage facilities for nuclear waste. The series shows the fateful and potentially fatal way to nuclear fission, which takes places within fractions of a millisecond, but whose by-products will keep radiating for another 500 or more years.

Medicine l, a deeply disturbing group of eleven photographs taken in anatomical or pathological research facilities, shows with frightening urgency the program of modern civilization, the Cartesian domination of nature. The pathologist dissecting corpses epitomizes the triumph of knowledge over death. Peeling and laying bare a human body for the sake of enlightenment conjures up a materialism that, according to Peter Sloterdijk, is more cynical than any other and that profoundly disturbs the balance between body, soul, mind, and emotions.

Medicine ll shows the new and unintended servility, even humility, of human beings. In this series on surgery performed on sensory organs—on eyes, ears, noses, and hands—we see the individual body submitting itself to institutional knowledge, completely surrendering to the prescribed technology. Hans Danuser’s choice of surgery performed on sensory organs implicates that we are about to enter a world where we won’t be able to trust our own senses anymore, exposed as we are to a multitude of flows of energy and information. We will be confronted with new powers that will rob us of our ability to make decisions according to our experience and our own volition.

For Physics l, Danuser traveled to Los Alamos, New Mexico, to photograph in laboratories where research on laser rays and nuclear fusion was done as well as the development of the notorious SDI anti-missile defense shield. He shows the attempt to attain total control of the earth by submitting nature to geometry’s iron grid and by amplifying energies. These photographs outline a (visual) world that dissolves any kind of familiar or comprehensible order and installs a new one in its place, enabling us to exert total control. Considering that light is a preeminent symbol of knowledge, the use of laser rays (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) gains a salient metaphorical quality: highly amplified knowledge may lethally disturb nature’s balance.

Chemistry l shows images of experiments in vivo and in vitro for pharmaceutical research in chemistry and analytic chemistry. Chemistry ll was shot at genetic research facilities for pharmaceutical and agricultural companies. They are the culmination of Danuser’s investigation of radical enlightenment as a means of dominating nature. Both series show Western civilization’s advance from the body to language, from models of matter to models of language, transforming the body, reality itself, to “a prosthesis of human intelligence” (Jean-François Lyotard). The photographs of chemical formula, the set-ups for animal testing, and experiments with living organs delineate the new demiurgic power to actually act as creator, crossing the “threshold of the natural structure of substance itself” in order to reach the place where “the most enigmatic cosmic forces were located,” as Peter Sloterdijk says. The will to know is always a will to power. The power over the body (of the animal, in this instance) gives us an organic, physiological knowledge that transforms the body into language, a legible formula. This in turn allows us to influence matter. After manipulating the core of physical nature, we now start to engineer biological and chemical structures.

Chemistry ll is the last of the seven series, probably the most radical, both photographically and thematically. The series reveals that there is nothing left to show. The essential has become invisible and functional. Images of refrigerated or heated organisms (a tobacco plant, for instance) hardly say anything about the fundamental interventions that are being performed here. Man is about to penetrate the inner core of substance and its structure. Ten years later, the human genome has been decoded. The ultimate structural laws are about to be conquered by man who will re-engineer them according to his will and his own intentions. With this series, Hans Danuser ended his In Vivo project.

The seven areas of research and radical transformation shown in In Vivo follow the values that have shaped the ways of the world ever since the enlightenment: generating and increasing knowledge and money in order to gain more power over the alien Other—nature, illness, death—and the Other closest to us, our fellow human beings. The most unfamiliar and, for many, the most frightening aspect of this development are the tools that contemporary science has given to the world.

Urgent and Stoic

In Vivo outlines many of the central themes of Hans Danuser’s later work. With a mixture of urgency and stoic calm, he approaches key areas and questions of contemporary society, where contradiction and cynicism become most obvious upon a closer look. This is the core of our knowledge and our power, almost off-limits to the public. It is a taboo zone because our future and our ethics are at stake. “We are enlightened; we are apathic,” as Peter Sloterdijk concludes in his Critique of Cynical Reason. “Let’s not talk about love for wisdom anymore. There is no knowledge whose friend (philos) we could ever be. It would never occur to us to love what we know. Instead, we have to ask our-selves how we can live with it without petrifying.” This feeling of apathy seems to accompany the processes represented in In Vivo and subsequent work groups, independent of their weighty meaning.

In the mid-1990s, Danuser began to include children’s counting rhymes from different cultures and languages in his exhibition installations. Counting rhymes—eenie, meenie, miney, mo—are used by children to order their world with an astonishing sobriety, even coolness. The result is arbitrary, but also inexorable: you’re out, period. With a laconic smile they seem to say: That’s the way of the world. You better get used to it. This demeanor creeps into the immeasurably more complex world of research and becomes, depending on the viewpoint, cynicism, its evil twin. In the context of genetic research, these rhymes put in perspective the scientific reasoning behind the decision, whether a gene (trait) may stay in an organism or has to go. In regard to erosions they highlight the accidental and incalculable nature of landslides and earthquakes. In regard to the vulnerability of the human body they underline that intentional violence, inflicted on humans by humans, can affect everyone as was horrifyingly and impressively evident in New York and Washington.

The tone of Hans Danuser’s visual “reporting” is still laconic today. This approach gives him the freedom to visualize monstrosities that have remained image-less so far and to present them to the viewer without any comment. Open, ambiguous, without commentary—and intense. It gives us the opportunity to think almost dispassionately about crucial questions facing our society and about life in general, after we have adjusted to the enormous power of their visual appeal.

Danuser’s methodological approach and his relation to the photographic image have changed since In Vivo. For the seven chapters of In Vivo Hans Danuser went to seven different “scenes of crime,” and like a documentary photographer, took pictures. Back in his lab, he condensed the photographs in multipartite essays that push back the documentary aspect in favor of an evocative iconic quality. Danuser opens the doors to explosive areas of civilization, but he does not insist on making visible what he has seen. He refuses to be a witness, so to speak, omitting the documentary narrative and the factual nature of his investigations. In In Vivo, he engaged in an aesthetic discourse between document and image. Nevertheless, the series was conceived within the domain of photographic documentation. From this perspective, he tries to explore, to tackle, and to blow up the limits of the very framework he is working in. The last series Chemistry ll hints at the further development of Danuser’s concept of the image. The series contains all the contradictions of a type of photography that insists on documentary visibility in the realm of the invisible. The photographs in this series conspicuously lack perspective in comparison with the other series. As is appropriate to the subject matter, there is no depth of field in the sense of a stand point or a vanishing point that would establish an order among the represented objects. The photograph’s vertical orientation is reminiscent of the mediaeval representational order; their flatness references all-over painting, such as informel or the color field painting of the 1960s. Chemistry ll heralds the dissolution of perspective’s order, of the security of above and below, of tangible reality. Frozen Embryo Series, Strangled Body, and Erosion perform this dissolution to the point of visceral irritation. Danuser entirely separates his photographic imagery from a motif that would provide a focus or from a descriptive approach to his subject matter. Thus, he enhances their potential to serve as screens for projections and their symbolic power. The shift from small-format to large-format photographs (59 x 55”) alter our encounter with the image. It becomes a physical experience, an equal of the viewer. It is an open pictorial space where our eyes may roam, search, question, and explore. The installation of the images transforms the exhibition space into a field of precarious experiences.

Topographies of Power

Nursery rhymes are attempts to structure a child’s world and play, providing a model of and a structure for the flow of life. Scientific models do the same, even if they don’t sound as poetic as “eenie, meenie, miney, mo.” Danuser’s approach hints at a fascination for models as tools for understanding the world. Very early on, in the late 1970s, he also did research on photographic emulsions. In Delta (1995)—his “matographies,” as he calls them, his “crazy” photographic game of signs—he continued to pursue this research. But Danuser’s approach is very ambiguous. He admires the models and the realities that were built with them, the very real interventions they brought about. With equal fascination, however, he seems to observe the collapse of models and the failure of attempts to impose order and to gain knowledge. His approach is imbued with the amazed “Oooh” of a child looking with wide-open eyes at a firework in the night sky. Mephistophelian places where enormous energies, surplus values, and immense knowledge are generated naturally attract a sorcerer’s apprentice.

Finally, I will use a scientific model to look at Hans Danuser’s work (after John Brockman, The Birth of the Future, 1987). In 1977 the mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot published a book, The Fractal Geometry of Nature, in which he proposes the use of fractals to mathematically quantify irregular natural forms. It is an elegant method which claims that although the number of conceivable different levels of order is infinite, the relation of these different levels of order will always be expressed in very simple numbers, like 1,2 or 2. If scientists want to chart a coastline, mathematically and geometrically, they will map it photographically from the air. With each attempt to adjust the coastline to the rigors of geometry, the map becomes less precise, a mere paraphrase of the actual coast. We would get a much more precise picture if we took pictures at a lower altitude in order to include every inlet, every spit of land. Finally, we would even show every stone and every grain of sand. We would have achieved a perfect representation of reality, one-to-one, but it would be of such an enormous size and complexity that it would not serve any purpose anymore. The world, however, is that complex and irregular.

This phenomenon, and its solution, shows astonishing parallels to Hans Danuser’s work. Ultimately his work is landscape art—icescape, bodyscape, erosionscape. He shows topographies that hide, even dissolve the real in infinite folds, curves, and overlaps. Under every fold there’s yet another fold. One smells good; the other doesn’t. One is a pearl-oyster; the other’s a Pandora’s box. For some we have an explanation, for others we don’t. We cannot even begin to fathom the whole. Once there was a man who had a hollow tooth. In this hollow tooth, there was a little box. In this little box, there was a note that said: …Or as Aldous Huxley wrote in The Doors of Perception, “Those folds in the trousers—what a labyrinth of endlessly significant complexity!” Thus, we can end our discussion of Hans Danuser’s work on a philosophical and conciliatory note. The world is. Frost is here to stay. We keep shivering. The processes that Danuser shows testify to a high critical potential, to a high charge in this fold and the next one. Mercy to those who lift them and ply them anew. And woe, if they lift themselves and slide and slide and slide.