Man's instinctive affinity with nature emerges in its most poignant form

on Sundays, or on the year's highest festival, during the holidays, with

a sketchbook resting on our knees or on a tree trunk, when our own

internal, pulsating, or external - in this case inert - nature plays the

role of a supporting prop for a re-energising absorption with nature as

the measure of all things. Mimesis, on free days; for it seems that at

other times our affinity with nature is less accessible.

For the next three years, the dictates of fashion postulate naturalness

in clothing, and the pope is given to mention the laws of nature in his

moral encyclicals - two observations introduced here with the aim of

injecting a breath of topicality into this contemplation of eternal

conditions. Nature has always been man's yardstick. The beauties of

nature have always moved us, we have always regarded certain things as

natural, we have always longed to be part of nature. It is still our

yardstick when we buy organic detergents, organic muesli or organic

bread in health food shops. The fact that the original word "natural"

has been replaced by "organic" is, although effective from an

advertising standpoint, ominous. Our eternal relationship with nature,

our affinity with it, is broken. Gernot Böhme has some very definite

things to say about this putative affinity. It is, he says, composed of

pairs of opposites, like the natural order of things as opposed to the

randomness of our laws, like man-made precepts as opposed to the

eternal, self-creating life principle, like the natural as opposed to

the artificial way of life, like the "natural condition" as opposed to

the "civilised condition", or like the self as opposed to the non-self.

But do these opposites still have a meaning, are they still more than a

mere placebo for our emotional solace?

At the beginning of the long path of man's anthropogenic influence on

nature was the command "subdue the earth." In the 14th century, when

Petrarch emerged from the musty darkness of the Middle Ages into the

light and climbed Mount Ventoux, he may have taken an aesthetic pleasure

in the view of the land, but he also planted another milestone in man's

domination over nature. Nowadays, now that nature is starting to hit

back (nature? What nature, I wonder), we are aware that something has

changed. We should have realised it a long time ago, for truly, which of

us really means nature when we formulate the word? Natura beef - yes,

but preferably pre-sliced; natural beauty - yes, but preferably with a

touch of cultivation; nature - yes, but preferably in the form of parks,

natural English parks as opposed to artificial French parks, because

they contain all that we like about nature but exclude everything else,

everything rough, wild, prickly or evil-smelling.

When Walter Mittelholzer, René Gouzy and Arnold Heim set off from the

lake of Zurich in a seaplane and flew over the dark continent to the

Cape of Good Hope, great regional importance was ascribed to the success

of technology in opening up new paths between "our little mountainous

country and far-off lands". Had their seaplane been called "Europe"

instead of "Switzerland", Mittelholzer would have been known as the

Petrarch of 1926, a Petrarch who climbed higher than the highest

mountain, who flew, flew, flew. Beneath him the world, at first southern

Europe, then everything that constitutes the alien non-self: dark,

incomprehensible, African nature, a nature that reminds us of our

origins, or at least some of them, not of Arcadian light and bright,

columned halls but of the dark, sub- and unconscious aspects of western

existence. Mittelholzer probably landed in a landscape rather like the

Ticino, like the southern slopes of the Alps, at the light, southernmost

point of the dark continent. But Africa really is different, for whereas

we Europeans ask: "what do you think about it?", the Senegalese ask:

"comment tu sens ça? What do you feel about it?". And then they dance

"it". But even they ask in French.

In his large landscape pictures, Rémy Markowitsch uses photographs from

books about Africa, books by Walter Mittelholzer and others, with

well-sounding names such as Martin Johnson's "Safari - a Saga of the

African Blue", books written in the1920s and 30s when not only

ethnologists but also surrealists and music-hall performers started

taking an interest in Africa. Africa, a vitally important continent for

Europeans, says Markowitsch, but also the subject of a huge

misunderstanding, probably from the very beginning. His investigations

of African (and southern tropical) landscapes took him to areas which

absorb our western projections like blotting paper: the heat, the

darkness and the damp become manifest - from two sides: darkness

encounters the exotic, in search of the red orchid. The pictures are as

large as Markowitsch's studio window and afford a vista - of "After

Nature".

Collecting and nurturing

At school, in the lower grades, not long after we learned to talk, we

collected autumn leaves of all colours, the hard-working ones among us

out of doors, in the woods, the lazier town children, like me, on the

school playground; we put the leaves in a book or between sheets of

paper, pressed, dried and later drew them. Domesticated exercises - or

memories - in collecting, nurturing, preparing, preserving and

understanding the nature of our fore-forefathers, of with-and-after

nature, using highly domesticated nature as our model.

One side of Markowitsch's work, a hidden side which is not immediately

evident, is this aspect of collecting. First of all books, perhaps,

containing written-down, categorised knowledge, with condensed views of

the world, from different times and "pressed" - printed - in different

techniques. Not collections of leaves or berries, but of cultural

assets, of illustrations of the world. Prefabricated, maybe, yet

Markowitsch handles them like raw materials, spotlights and investigates

them, as if he wanted to find out what they really are, transforming

opaque material into an illuminated screen. The Enlightenment threw

light on things like this, and Modernism did it in increasingly

elaborate ways, progressing from views to insights, probing beneath

appearances, discovering structures behind the surface, and pushing the

boundaries of the visible further forward, further in. At school, even

in the lowest grades, we went regularly (probably too regularly) to be

X-rayed. Ever-greater, ever-deeper, ever-clearer truth was the

objective, recognition of structures and their deviations which meant

illness. Markowitsch's X-rays, his visual palimpsests, do the opposite:

they make things unclear by making them visible, they blur focal

sharpness, they put information and its carriers on an equal scale. The

rustle of paper, the first material carrier, or the chuntering of screen

dots, the actual carriers of information, interfere with the portrayal.

In Markowitsch's plant pictures, his arrangements portray truths about

the printing quality of the 1960s rather than about the world of plants.

P1, for example, with the original rubber plant (Ficus elastica

Tricolor) on the left, its easier-to-cultivate relation (Ficus elastica

Decora, grown in 1945) on the right, and the transilluminated variety of

the rubber plant called Ficus deltoida/Ficus diversifolia, the fig tree,

are a celebration of saturated colours, the taste of our youth, the

spirit of the "everything-is-possible, everything-is-tameable" of the

1950s and 60s. When light is lacking, it must recompensed by fertiliser

- or so it says in the book "Mehr Freude mit Blumen und Pflanzen" ("More

Fun with Flowers and Plants") which Markowitsch illustrated. When the

spirit is lacking, the printing must be more colourful. The rubber

plant, once a tropical plant, then an indoor plant for indoor tastes, is

almost as easy to look after as a nylon shirt. Just as plants grow to a

size compatible with their own - or man-aided - strength, the size of

Markowitsch's pictures is variable. He takes mimesis to the point of

absurdity. His mechanical copy of a mechanically printed copy of a

mechanically photographed copy of some reality or other acquires its own

monstrous pictorial reality, finally assuming the appearance of a

digitally produced plant arrangement, like a just-produced, somewhat

alienated original, a "Natura naturans", self-generating nature gone

slightly wrong. Markowitsch's commentary on the 145-year-old craze for

photographing the world.

Cadavres exquis

In his picture of the Simmental cow "Flamme" from Erlenbach and the

brown cow "Liebi" from Illgau, both of them fine animals and both

portrayed in proud profile photographs, Markowitsch has crossed and

blended the two breeds - although it is not possible for the eye to

comprehend them both simultaneously and completely. The ancient breed of

Swiss brown cattle is characterised by its great adaptability, and the

animals' pedigree dates back to the turf cattle of the pile dwellers.

The Swiss spotted cattle which "originated" in Switzerland, or were

introduced in antiquity, are divided up into the red spotted (Simmental)

and the black spotted (Fribourg) breeds. Protected and unprotected

pedigrees, the pride of the first farming society. A few years ago,

television showed a farmer and cattle dealer negotiating by handy

telephone in the midst of the still idyllic alpine landscape about the

sale of Simmental cows direct from the green meadows of Switzerland to

the USA. This was at a time when the Americans were buying large numbers

of this breed because they seemed ideal for the meat-producing and

meat-consuming world. For their part, the Swiss farmers were interested

in crossing Simmental cows and American bulls in order to produce a

cross-breed with a higher milk yield. However, since the Simmental cow

is as much part of the tourist image of the Swiss Alps as the white

peaks of the snow-covered mountains, and as indigenous to the Swiss

mentality as Toni milk, certain aesthetic problems arose. It was

impossible to use the sperm of the original American super-bulls because

this dark-coloured, and sometimes even black, breed would have

conspicuously changed the brown spots of the Simmentals. So it was

decided to use the sperm of an albino, and thus much lighter-coloured,

bull. In consequence, an inexplicably large number of cows died of an

inexplicable disease. And thus the aesthetic problems gave rise to

physical, i.e. veterinary and financial, questions; not, however, to

ethical issues since we still ascribe animals to external nature, beyond

the range of ethics.

We live in "Nature in the Age of its Reproducibility"("Die Natur im

Zeitalter ihrer technischen Reproduzierbarkeit"), to quote Gernot

Böhme's adaptation of Walter Benjamin's famous title; we live with

nature, and we are nature itself. Up till now, we have thought of nature

as always having existed, and of technology as our creation. Were the

two really so strictly separate as we imagined them to be, we would have

had to be content to drink sour wine and eat sour apples. Nowadays,

however, the fusion between nature and technology is quite as

significant as nuclear fusion. And although we have by no means

exhausted nature, and although for centuries we had to be content with

research and imitation - with mimesis -, intrepid, inquisitive mankind

has discovered some secret keys which promise to bring about a

fundamental change in the nature of our interventions. We human beings

have mutated, crucially, from imitators to creators. And, oh

megalomaniacs that we are, we have lost no time in proclaiming that we

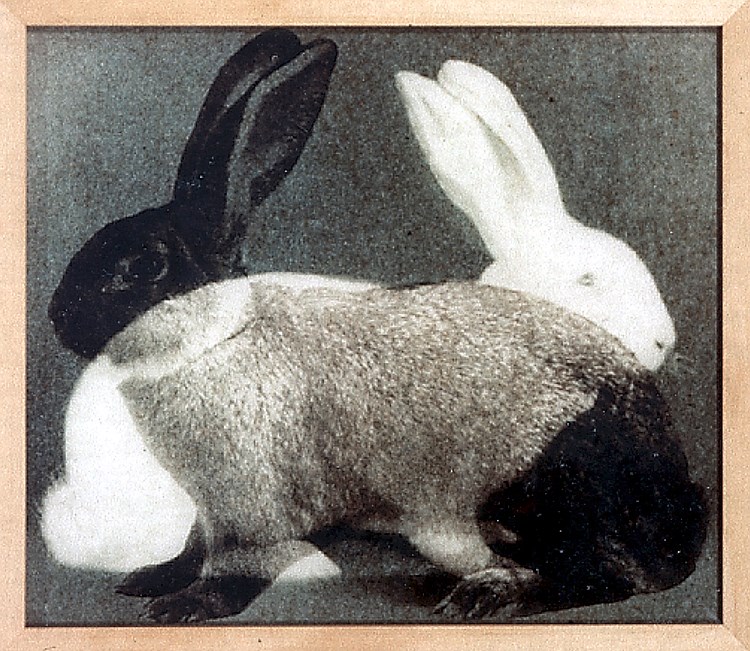

are fully in control. Markowitsch's crosses between typologically ideal

cows, pigs, rabbits and dogs are reminiscent of the surrealistic

practice of cropping, doubling, multiplication. The surrealists wanted

to conjure up the phantasmagoria, Bataille's "informes", to help the

suppressed counter-world to come into its own. Markowitsch's "cadavres

exquis" permit Dr. Doliitle, having at last reached his objective, to

find the push-me-pull-you. His almost motionless, enlarged double animal

portraits on the scale of 1:1 generate a tension through the ambiguity

between the dignified portrait and the mechanical transillumination, a

tension which forebodes the techno-nature-orgies of the future. "So that

we can sleep well again...", as a campaign for gene technology would

have us believe.

As a precaution

The political scientist and traffic specialist Walter Seitter is

interested in the book as printed language, and it is on the example of

a book that he presents his investigations on the exact nature and

management of the carriers of "air vessel modulation" precipitation:

"The state of the book when it is being used consists of a series of

single states, which we call 'the state of being open', whereby each

'opening' opens up a double page: two connected, juxtaposed leaves each

showing one of its sides. (...) If we begin by opening the book at the

place which we in the west call 'the beginning', the first double page

consists of the reverse side, the front side of which was the title

page, as well as the front side of the next, second page. (...) The

structure is based on the fact that the book (in use) is a series of

double pages, of which each one covers all the rest (and everything else

as well). If this covering up were not to function, then, with one

double page, we would be able - obliged - to read all the others, i.e.

we would read all or nothing. (...) Perhaps the urgency of the second

principle of optics only really becomes clear on this example: it is

because we see only the outermost, extremely thin surface, only because

the surface is opaque, that we can see it, that we can see anything

(anything specific). The imminent palimpsest effect is reinforced by the

fact that the next layer of writing directly 'behind' the words being

read (...) consists of 'back-to-front' letters. Thus the opacity of the

page must be adequate to cover not only all the other pages, but also

its own reverse side. The page must cover itself - so that it is

visible." (Seitter, Physik des Sichtbaren, in : "Tumult", Zeitschrift

für Verkehrswissenschaft, No. 14). The over-insistence of the

descriptions in these textual extracts has an element of absurdity, and

I think, although I do not know him, that the author would gladly admit

it, albeit not without a "yes, but...", since here he is involved

exclusively with the physics of the visible, which means that whereas

other people may read books, he is primarily concerned with what we see

when we open a book, how we hold it, and what a book containing printed

language looks like, materially and structurally. Rémy Markowitsch does

something similar, with similar meticulousness, in order finally to

arrive at the opposite. "The cycle 'After Nature' examines the use of

photography in books", he wrote in telex-style notes intended for his

own use. "It registers what has been registered and X-rays forms of

portrayal in printed photography. (...) The new image emerges at the

same time as the printing of the second photograph. I reproduce

reproductions." He is not interested in language and its book form, but

in our common picture archives, books, which contain the pictorial

worlds of the 20th century and with them ways of handling pictures, the

arrangement of the page, the sequence, the printing techniques.

Subsequently, rather than describing these visual archives he - himself

a visual artist - exposes them, X-rays them, enhances their very opacity

in order to wrest a picture from the two-fold deposit. This has

something in common with visual surgery: "cut-out" books. What we see is

real, it is really there, it is revealed as it is through

transillumination. The visual worlds ,which are as it were dissected

through combination, themselves deal with injuries and deformations. One

kind - which were modelled on the "Lehrbuch für häusliche

Krankenpflegekurse", third edition 1944, published by the Swiss Red

Cross - imitates the state of being injured and simulates the specific

measures required for healing; the other - which refers to "education in

deportment and behaviour", published in 1967 by the Volkseigener Verlag

Berlin 'Volk und Wissen', warns against the beginnings of "changes in

the physical and spiritual demands on the workers brought about by the

technical revolution...", by means of the simulation of preventative,

precautionary gymnastic posture exercises. Rémy Markowitsch simulates a

classically artistic approach by allowing us to gain an inkling of the

presence of creative figures which provide a counterpoint to the theme

and its mechanical appropriation, and by giving the transilluminated

subjects a rigid frame, as if protecting their fragility and artistic

ingenuity and preventing any possibility of their leaking out into

space, into the poorly-trained banality of contemporary everyday life.

Urs Stahel

Translated from the German by APOSTROPH Lucerne

See Urs Stahel: Nach der Natur, published by Galerie Urs Meile,

Lucerne, 1993, and

Bilderzauber, exhibition catalogue, Fotomuseum Winterthur, 1996