Photo: Rocco Casaluci

We live in the west in a world, that is generally referred to as the post-industrial era. Over the last 30 years many factories have been closed and production processes have been delocalized. Europe is changing face, turning itself into a great service providing continent. The concept of post-industrial is, however, only effective, if we relate it to the fact that, despite having moved many enterprises to Asia and delocalized production processes, we continue to derive profit from the economic results obtained. It is less fitting if we consider that the cardinal points are still those of an industrial type economy: inventiveness, investment, production.

In the past, society has often experienced a certain unease in its relationship with industry. It is clear that industry responds to our needs, brings enormous benefits, creates prosperity and makes our lives easier. But how do we talk about it? It is evident how the pleasure in beautiful things is strongly embedded in our society. We talk about the beauty of the landscape, of works of art, fashion, beautiful people, beautiful cars. In contrast, we speak much less willingly when referring to production processes. It is as if a recurring image, evoked by the heavy industry of the past, still loomed over the entire sector of industrial production. So, if on the one hand we readily discuss extraordinary results and exceptional products, on the other we tend to overlook the difficulties production and producers encounter. And in this sense industry is sometimes alluded to as society’s grey area.

This issue is reflexted easily in the controversial relationship the industrial world has with its images. For decades, photos of factories have been treated with total indifference and it was not uncommon for them to be thrown away when a company moved site. It is only recently that we have started to re-evaluate and retrieve them, thus realizing we have eliminated the evidence of almost half of the world, the history, the universe of industrial production: a world that provides a valuable key to understand our lives, our thoughts and our activities.

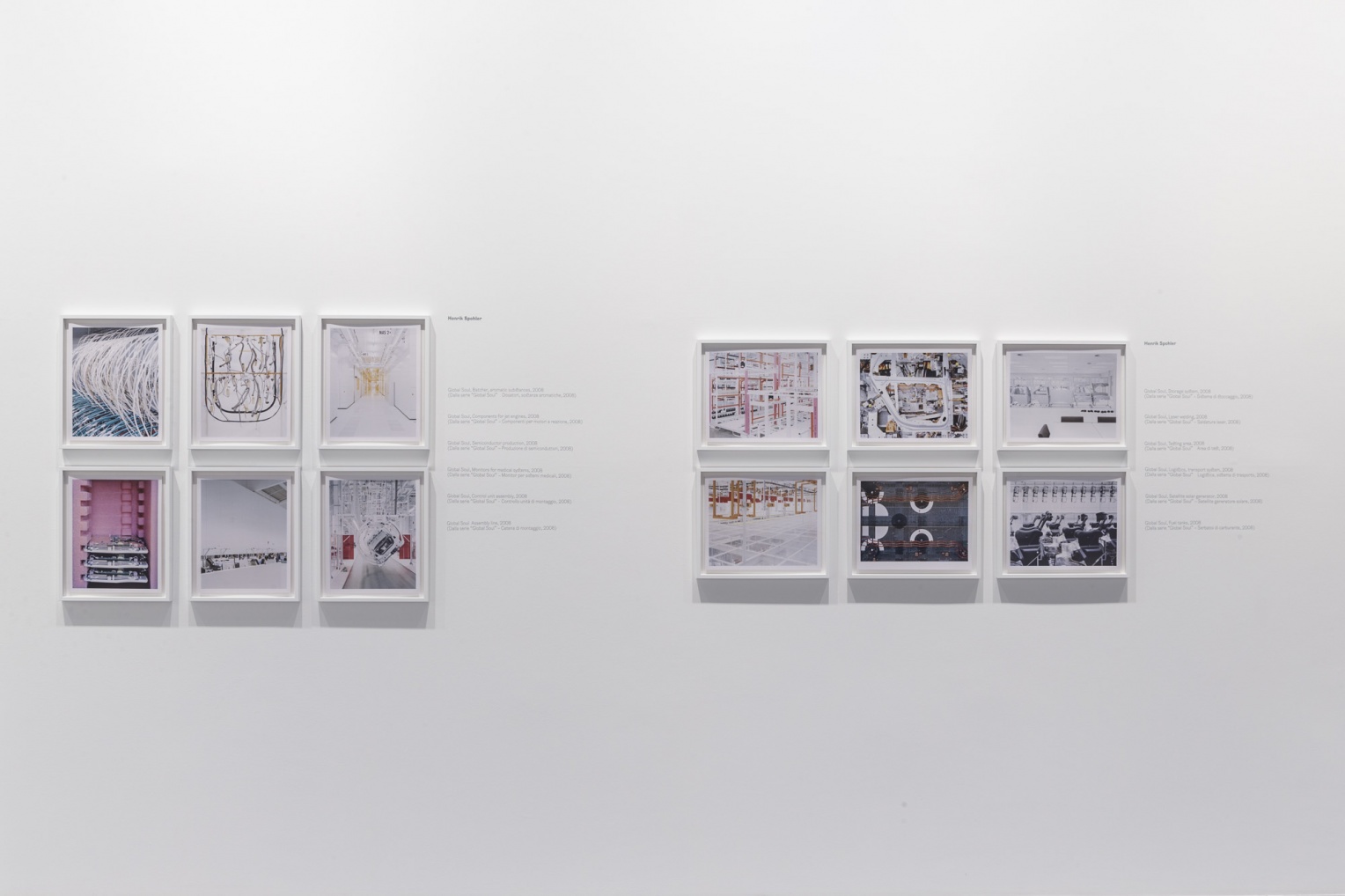

This first exhibition that is shown at MAST, the new center of Industrial culture that opens tomorrow, has been drawn from the Fondazione MAST’s collection of industrial photography and is divided into five thematic sections:

1. Section: Work/Workers

The factory work has radically changed since the 18th century and the start of the Industrial Revolution. While 14-hour work days and 6-day work weeks were previously the norm, today in Europe the average work schedule is 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, and tending to grow even shorter. At the same time, productivity itself has more than doubled. “Blue Mondays” are a thing of the past. Meanwhile, the image of masses of workers pouring out of the factory at 4 p.m. has all but vanished in Europe. Flextime, halftime, or even completely automated production lines and robots have clearly thinned out this stream of human labor.

2. Section: Industrial aera/Industrial plant

Factories were often erected along city peripheries, reaching out into the countryside. Because the old centers of the European cities were so densely built, this was for security reasons, as well as for space: only at the city’s edge could the industries ever expand. Yet as industry grew, so did the cities, often giving rise to inner urban areas that could only develop inwards, becoming even more condensed than before. In the 19th century, factories were often built for prestige, with magnificent façades emulating palaces and soaring chimneys that seemed to compete with the city’s church towers. But the cool practicality of the production line was well suited to modernist architecture.

3. and 4. Section are dedicated to Chiaroscuro and Visibility/Invisibility

The theatre of industrial production is examined through pairs of contrasting images. “Once upon a time and now”: the black, sweltering factory of the past, overflowing with workers, and the white, aseptic, empty pavilions of our own day. Then the contrast between the imposing, visibly decipherable machinery of the beginnings of industry and the silent, enigmatic instruments of contemporary productions.

5. Energy Flow, Traffic Flow, Data Flow

And concluding the itinerary, we show what any industrial production needs to function: energy, transport and communication. Electricity allows humans to electrify, literally. Electricity has served as a sure sign of progress, not only in the Soviet Union – where socialism was declared to be the link between electricity with the Soviet power – but also in capitalism. Dams, for instance, demonstrate that the natural powers allow themselves to be harnessed, even as their threatening potential continues to slumber behind the barriers. And the transformers, crackling loudly with occasional electrical arcs, show that humans can now host their own light storms. Man Ray’s wonderful multi-part image sequence is an attractive symbol for this.

With these five chapters and the works of 47 photographers, MAST begins the writing of a history of industry and opens a discussion on industry itself, starting from its own photographic patrimony.