We constantly yearn for intactness. For an intact childhood, an intact marriage, an intact community, as well as for an intact and uninjured body, an intact natural environment and now even an intact planet. No matter how we try, we cannot pinpoint the source of this yearning. Yet it seems to be a fundamental constant of our existence; a genetic or phylogenetic imprint on our lives that social philosophers often associate with birth, the pain of separation it brings and the subsequent painful experiences that we gradually seek to overcome, both individually and as a society, through our deep longing for wholeness, integrity, oneness. As Emile M. Cioran puts it so succinctly in his treatise The Trouble With Being Born «We do not rush toward death, we flee the catastrophe of birth.»

Step by step, in the course of human history, personal separation and individual injury have broadened into a universal emotional wound. Copernicus and Galileo discovered that the earth, and therefore humankind, were not at the centre of the universe, while the discovery of the subconscious and unconscious by psychoanalysts broke our ur-trust in the power of the human race and in the potency and sovreignty of its subjectivity. We humans have to acknowledge that the subject is no longer master of all it surveys, and that it is both consciously and unconsciously the product of «dark» powers (Arnd Pollmann). As Georg Simmel pointed out in the early twentieth century, the centrifugal forces of modernism – including the separation of home and workplace, the division of capital and labour – correspond so strongly with the fragmentation and shattering of the subject that they have become a specifically modern experience of social disintegration, arousing the human need for wholeness, intactness and integrity.

Little did that change in the postmodern and present era. While idealistic art appeals to our fantasies and hopes of renewed intactness and integrity, realistic contemporary art has focused in the past three or four decades on pinpointing, emphasising and analysing what drives the social and psychological upheavals suffered by many people – and ultimately also does so with the same underlying desire for intactness and integrity. Contemporary photography is no exception. Young artists often thrust a finger, sarcastically and scathingly, into the wounds of our socio-economic body, reminding us – even where our romanticising retrospection might still have clung to some notion of unity – of the inequities, the concealed injustices, and the fatally blinkered viewpoints that have allowed us to sugarcoat both past and present alike.

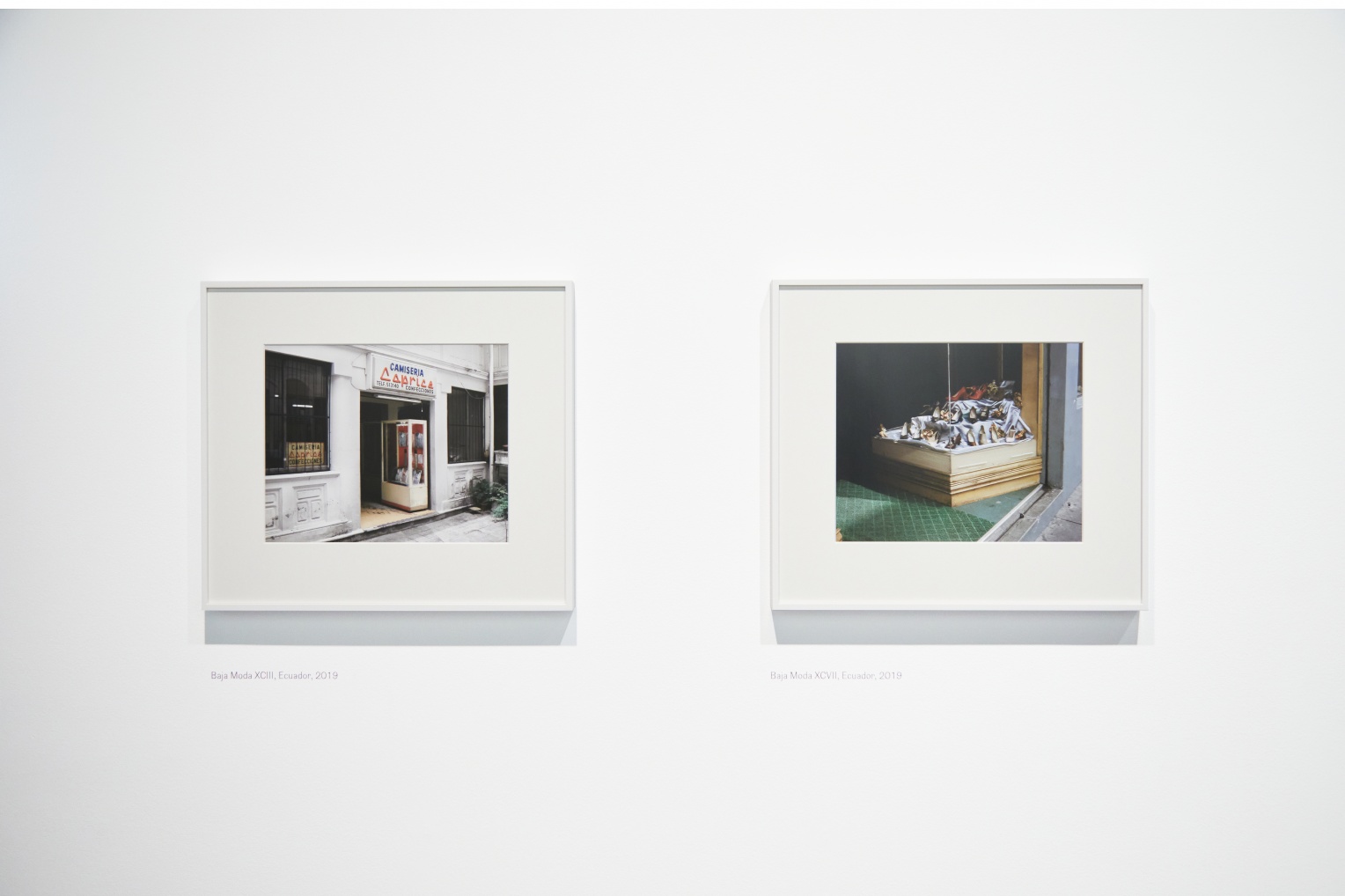

Every two years, the MAST Foundation Grant for Photography in Industry and Work gives five young artists the opportunity of delving into the industrial, technological world and exploring its systems of labour and capital, invention, development and production. Often, they surprise us with new takes on its inconsistencies and shifts, revealing phenomena and perhaps even abysms that we had previously overlooked. Pablo Pedro Luz, for instance, in his series of photographs of streets and shop windows in Mexico, addresses the market upheavals in which local production and distribution sources are being squeezed out by multinational concerns and global processes. His keen eyes sharply note the last vestiges of local trade and fashion, and he photographs these shops like small-stage theatres that give an insight into a gradually fading and disappearing folk culture. The glass of the shop windows acts like an interface between past and future, between basa moda and alta moda, between customary local wear and the global logos and brands of image-driven fashion that can be found on high streets and in shopping malls throughout the world.

Finnish artist Aapo Huhta lets words and images clash. In his visual and audio installations, the image-recording system known as «photography», now almost 200 years old, rubs up against the analytic systems devised by the likes of Google and Microsoft. The rural landscape of Finland, with its old-established villages and its handed-down traditions that are so simple and so far removed from current global behavioural developments, are analysed five times over by digital and algorithmic recognition systems and then, combined with the information about the probability of events shown in the photographs, they are commentated in a shakily mechanical voice. The multivalent ambiguity of what has evolved naturally is measured in dual 0-1 sharpness, with the result that two worlds glide past one another, each of them oblivious to the essence of the other.

The video and photo installation For a Few Euros More by Chloe Dewe Mathews casually and elegantly links three or four eras and three or four fundamentally different branches of industry with a variety of social and monetary structures. The scene is the vast Mar de Plástico, or Plastic Sea, situated just south-west of Almeria, between the sea and the Sierra Nevada – a 200 square kilometer agricultural zone that produces half of Europe’s fruit and vegetables. It is the world’s largest producer of greenhouse-grown agricultural goods. Tensions often arise between the local people of Andalusia and the predominantly African workers. This was a poverty-stricken region before the systematic agricultural expansion of the 1960s. Before that, it had been exploited for a century as a major hub of lead, silver and gold mining. It was in the 1960s, too, that Sergio Leone used the abandoned mines as the backdrop to his famous Spaghetti Westerns. Today, the film set is a tourist magnet. In her video, Chloe Dewe Mathews follows an itinerant African worker called Manuf, as he meanders and glides, like a probe or drone, through the very different worlds and eras of these four industries – agriculture, mining, film, tourism – and combines the exploratory journey with compelling ambient sound.

An intact life is, above all, a fantasy, a longing, an aspiration. And because, in our present time, this is so very rarely achieved, even in part, it is often projected into the mythical past of a life already lived, a tribal community, an epoch. That is always a dangerous path to tread because, while it can almost never be susbtantiated, it can be heightened and misused to shape notions of a superior civilisation or national culture.

Alinka Echeverria’s three-part work is both a paean and a plaint. On the one hand, she celebrates Grace in an LED animation based on a photograph by Berenice Abbott: Grace Brewster Murray Hopper was an American computer scientist and programming pioneer. She rose to the rank of Rear Admiral in the US Navy Reserve. On the other hand, in an installation with various printed glass plates mounted on plinths, Echeverria celebrates Hélène – a French name, rooted in the Greek “ēlē“, meaning light, torch, bright – which, as she points out, was common during the silent era of French cinema when young working class girls were given the job of splicing. The installation highlights the dexterity of these cutters, which was so crucial to the history of film. Finally, in a huge mosaic and multi-part collage, she also celebrates Ada: Ada Lovelace (née Byron), titled Augusta Ada King-Noel, Countess of Lovelace, was a mathematician who is widely acknowledged to be the first computer programmer. The artist celebrates these three real and imagined figures as represnting a history of the hidden contributions made by women (in film, photography and computer science). In this respect, her homage is at the same time a «j’accuse» aimed at male-dominated historiography, and poses the question as to the role women will play in the workplace of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or Industry 4.0.

Maxime Guyon, by contrast, does not play so much with breaches or dichotomies as he does with exaggeration, duplication, and blending. He sticks to neutral or neutralised tones, with the exception of some bright red and yellow functional elements that highlight essential parts of these complex objects. . «The technical quality of the photographs matches the technological quality required to lift these large metal masses from the ground and into flight. In Guyon’s images, everything is in focus, from the extensive floors to the details, from the skeleton of an entire cabin to the smallest rivet. There is a sense of control, of a fragmented but total vision, artificial, almost fetishist.” These are the words of Milo Keller, in his contribution to this publication. He goes on to say that “Artificial lights emphasise the sculptural nature of the forms in a studied, parameterised and calibrated aesthetic virtuosity that surpasses the sterile technical display and imposes a formal register that is both attractive and alienating. We are in a globalised, homogenised, supranational space.” Maxime Guyon’s hyperrealistic images catapult us into a space that is as concrete as it is unreal; a space in which, it seems, the ideal and the real have become inseparable, and in which mourning and fulfilment are suspended in the eternal promise of technological redemption. In these images, life and technology are suggested (perhaps asserted), blended together as one – following their journey into the possible future of a synthetic intactness.