Alessandra Spranzi’s photographs enable us to feel and grasp the poetry of the marginal.

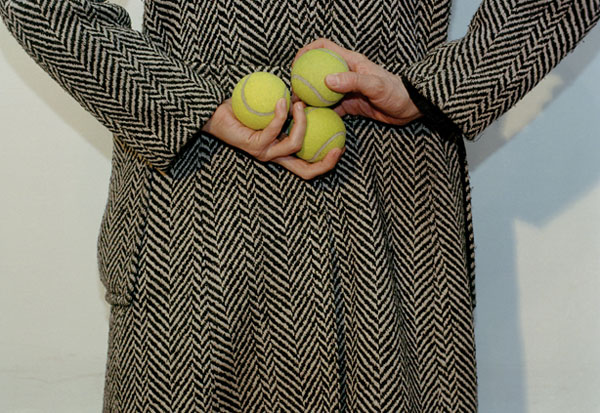

She wears a coat with a herringbone pattern, black and white, white and black, she turns her back to us. The arms are twisted behind her back, she holds yellow tennis balls, two in her left, one in her right; together, the balls forma triangle. “Mani che imbrogliano” was the title of an exhibition by Alessandra Spranzi in Bologna, which was opened with this photograph: “Cheating Hands.”

The coat seems worn, the balls are used. The photograph was framed and mounted on a black wall blocking the view into the exhibition. We recognize that the figure, also standing before a wall, and that what she most wants to hide, is revealed. Cose che accadono is the title of the photograph, things that can happen. So do the hands still betray, just because of the intention? We don’t know.

The late Roland Barthes avoided conspicuously grand, pugnacious, striking words and wrote, “Meaning cannot be attacked frontally, you have to cheat, steal, be subtle.” Because we often generalize, abstract, and systematize too quickly, he tries to keep the meaning of things in abeyance for as long as possible—just like Alessandra Spranzi, who here probably personally holds the three tennis balls in abeyance, as well as the meaning of the picture.

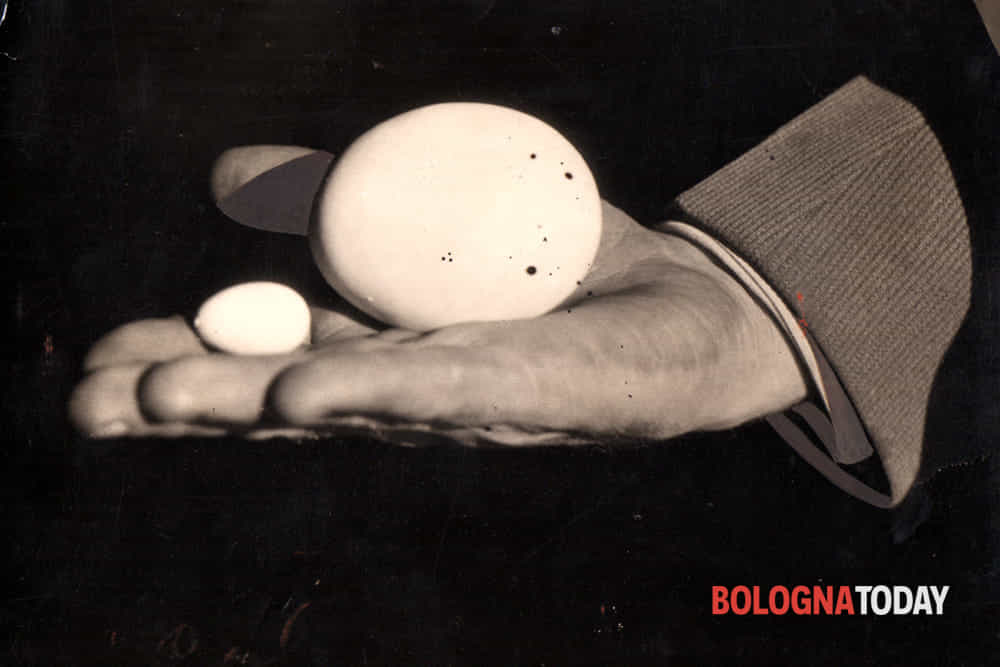

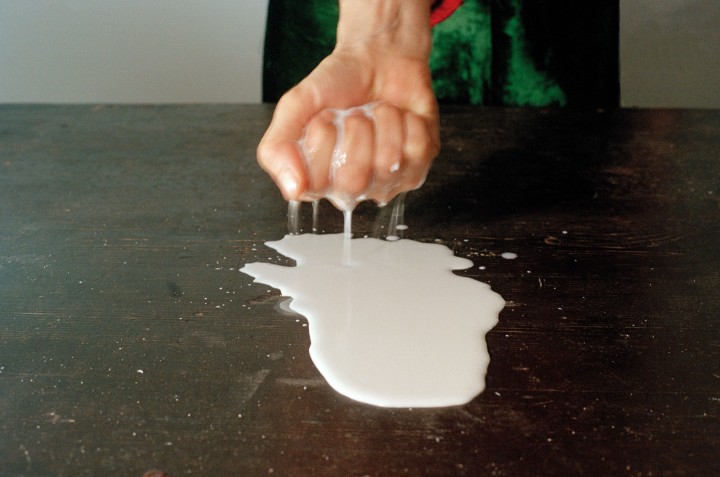

In other pictures, a fork asks the knife to dance on the rim of a glass; a tablecloth, embroidered with a great deal of passion and skill , floats above a table that is not there; in Quando le terra si disfa (When the earth falls apart), objects struggle against and for gravitation; a woman with a beard close to a table by candlelight; an eagle as petrified as he faces an hypnotist; Bicchieri a righe, striped glasses, form a transparent large family before a black background; a hand presents simultaneously a large and a very small egg; and some liquid is unsuccessfully poured into a glass lying on a surface. All of it often before a black background—The set is black, we read in parentheses in the legends.

Acting within the picture, Alessandra Spranzi also tries to grasp milk with her hand, to beguile a small bird with a flute, carry books on her head. Finally, she decorates a place setting with festive flames. We remember the work Stiller Nachmittag by Fischli Weiss and the laconic apposition: “The balance is most beautiful just before it collapses.”

The exhibition in Bologna (at P420) was installed by eye, all works approximately at the same height, the groups of four or six photographs a little higher, one video box was set apart, but nothing was measured with a measuring tape, nothing was mathematically exact, nothing systematized. Alessandra Spranzi takes photographs, but she also appropriates printed matter, directly or photographed, which gives her photographs the impression of something used. Like a second-hand pair of trousers, a used handkerchief, a slightly soiled napkin. Translated into action: like a “worker” lazily hanging out.

Photography loves high gloss, a brilliancy that lets us forget the support, like a perfect car finish. Today, photography loves the light-emitting diode; the screen that makes the colors and the world glow, as if they were synthesized. That over there! Exactly! Beautiful! I want it! With Alessandra Spranzi on the other hand, things are quite the opposite. We don’t see the shiny facades, but the wilted, grayish timber, the self-made quality of the structure, the tilting of truth, the wrinkles in the face, the dissolution of order.

We always want to touch her pictures because they seem material, because they, as it were, want to return to the realities from which they originated. We want to listen to her pictures because they pose questions, because they seem to speak, just as the wavy hair of a woman, photographed four times from behind, fall differently each time, speak differently, and in the excitement they misspeak.

The German artist Hans-Peter Feldmann once wrote: “A meadow, really green, dense grass, no weeds, no flowers, juicy grass. Not very large, perhaps 20 x 20 meters. And around it a wooden fence. The classic kind, vertical wooden slats, pointed at the top, perhaps 1.5 meters high. Horizontal slats hold everything together, a post in every corner. Beyond the fence the same meadow, but already a little less ideal. Here and there a tree, a path, big stones, houses in the distance, and so on, the world. And the meadow within the fence is called art, and everything outside the fence is called world. And then suddenly the fence falls down. Suddenly that is also no longer art —or art is everywhere. And suddenly you no longer have a problem…”

Alessandra Spranzi from Milan is a rag collector; like Peter Piller, Moyra Davey and Zoe Leonard, she intentionally blurs the line between picture and matter, between true and false, between “art” and “world,” she questions orders and gives them a small kick so that our sense, our mania of systematizing is ruptured and disrupted. As if during a walk we would glide with our hand over the world, like on a handrail, and in so doing feel every unevenness, every deviation; feel the signs of the times in our palm.

Alessandra Spranzi appears in her photos and videos like today’s influencers on the Internet. Only her wares are not brand new, her truths are shaky, her plots questionable. Once we turn the rock, the stories begin immediately. Humble materials, humble situations ignite in an intensive way our poetical sense.

Things are, things happen, between being there, being picture, and being crazy—always just next to perfect utility to which the world all too often wants to be optimized. The work of Alessandra Spranzi proposes a poetry of doing magic and of hesitating, of the marginal in an era of high performance and high gloss. Also in the numerous small booklets that Spranzi publishes at irregular intervals. These booklets provide, how could it be different, more haptics, more smell, and more emotion than these digital data here.