The challenge contained in the eighth volume of C Photo is threefold: Toledo, el Greco and the year 2014. The challenge of visually capturing the immense history and complexity of the city of three cultures—an epithet that serves as a tourist attraction—, where Jews, Christians and Muslims lived together, in a fortress erected on a river bend; city of swords, the Inquisition and this current Toledo whose beauty could languish day by day, paling before the never-ending hordes of tourists.

El Greco: the wonder of Toledo. The individualistic genius of painting, forgotten and rediscovered three centuries after his death, greatly inspired painters such as Cézanne, Picasso, Beckmann or Kokoschka. German expressionism is also profoundly influenced by this artist. The sharp figures, jagged skies and murky layers are recurring elements in modernist expressionism. The first decade of the 20th century saw the blossoming of pictorialism, a movement that tried to distance itself from infamy, mechanical sharpness and the loss of creative capacity through photographic tools and which approached symbolism and pictorial impressionism.

Pictorialism tried to conceal its nature so as not to be perceived or accepted as mere photography: a mechanical and chemical instrument that portrayed the world as being incredibly close and clear from a one-dimensional perspective. This movement intended to distance itself from the burgeoning industrial modernism that radically changed nineteenth- and twentieth-century society and at the same time tried to take refuge in the existing spiritual values through sentimental and intense images. A heretical question can be posed in this sense: How can photography allow itself to be influenced in a positive way by a figure as incredible as that of El Greco, so far in the past and whose role within modernism is still widely debated? This is the great and threatening second challenge that the artists who participated in ToledoContemporánea faced while creating their photographic series.

Lunch Included is the title that Philip-Lorca diCorcia has given to the eight Polaroids published in this volume, which he took during his stay in Toledo. Eight magical yet reflective images that he meticulously ordered in the shape of a cross once they had been taken. A symbolism pierced by a double crosspiece, perhaps guided by the attempt to bring to mind an imaginary connection between the Church of East and West. The uppermost image is dark, almost sombre, and literally offers the head of Saint John the Baptist on a silver platter. The other photographs show two views of Toledo, which through double exposures slowly dissolve into a thick layer of clouds. An inverted epiphany. The vision exhales downwards. The predella, usually located under the image of the altar, seems to bring God's chapter to an end, as if cloaking it with a heavy, dark tarp, completing in this way the connection between the earthly and celestial. Philip-Lorca diCorcia creates a work that is worthy of the most delicate chamber music, which subtly brings together the conceptual reference to Toledo and El Greco. On occasion, the hectic and frantic movement between heaven and Earth that happens through savage, wandering clouds in the paintings of El Greco is expressed in this photographic work but in just the opposite way. Cautiously, without meddling.

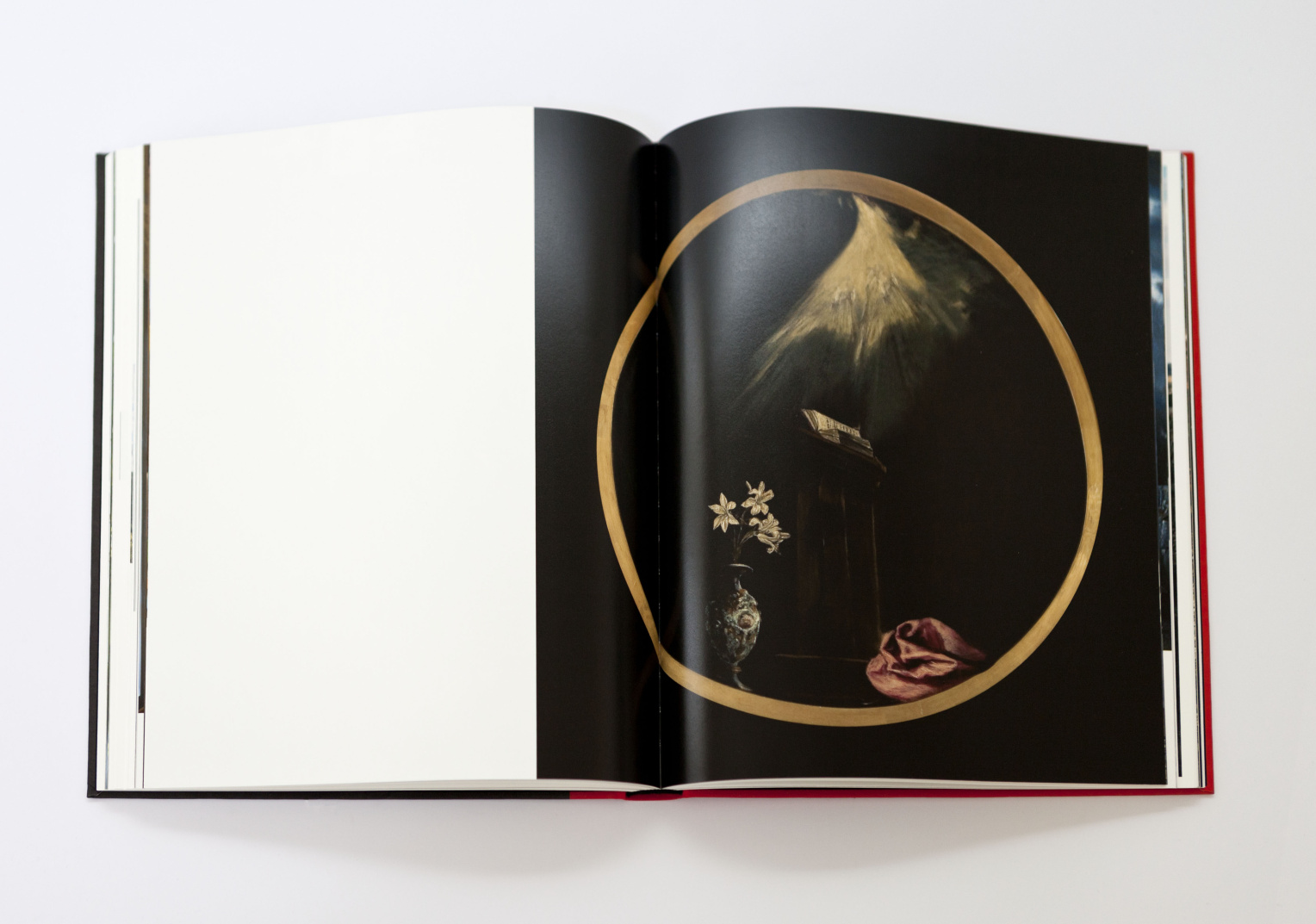

José Manuel Ballester has also focused his attention on El Greco's shattered skies, reproducing with expressive strokes in his images what the artist captured with movement, intensity and energy in his skies, in his clouds, in his gaze towards the heavens. Inspired by the creative structure of the painter, Ballester removes the skies, clouds and subjects and combines them in a new photographic painting that merges with his own perspective of Toledo, creating an amalgam in which the photographed universe blends together with the painted one: a past world and a present one.

The Argentinian photographer Marcos López dove, along with hundreds of tourists eager to take snapshots, into places full of history in order to find his image, his point of view, his poetry, his way in Toledo. And finally, he lives an apocalyptic experience, but, as he himself states, it is all in vain. López then finds shelter in his hotel room and builds his own temporary kingdom with plastic toys, with the history of Toledo as backdrop, pretending to be a templar. His Self-Portrait in the Hotel Room gathers more objects in a sort of theatre of the absurd: a perfectly hung t-shirt with El Greco's self-portrait and two heavy suits of armour on either side of the bed, as if they were anonymous guards, live alongside the usual hotel-room amenities. To top it all off, the artist fights a duel in the bathtub with a templar knight "made in China".

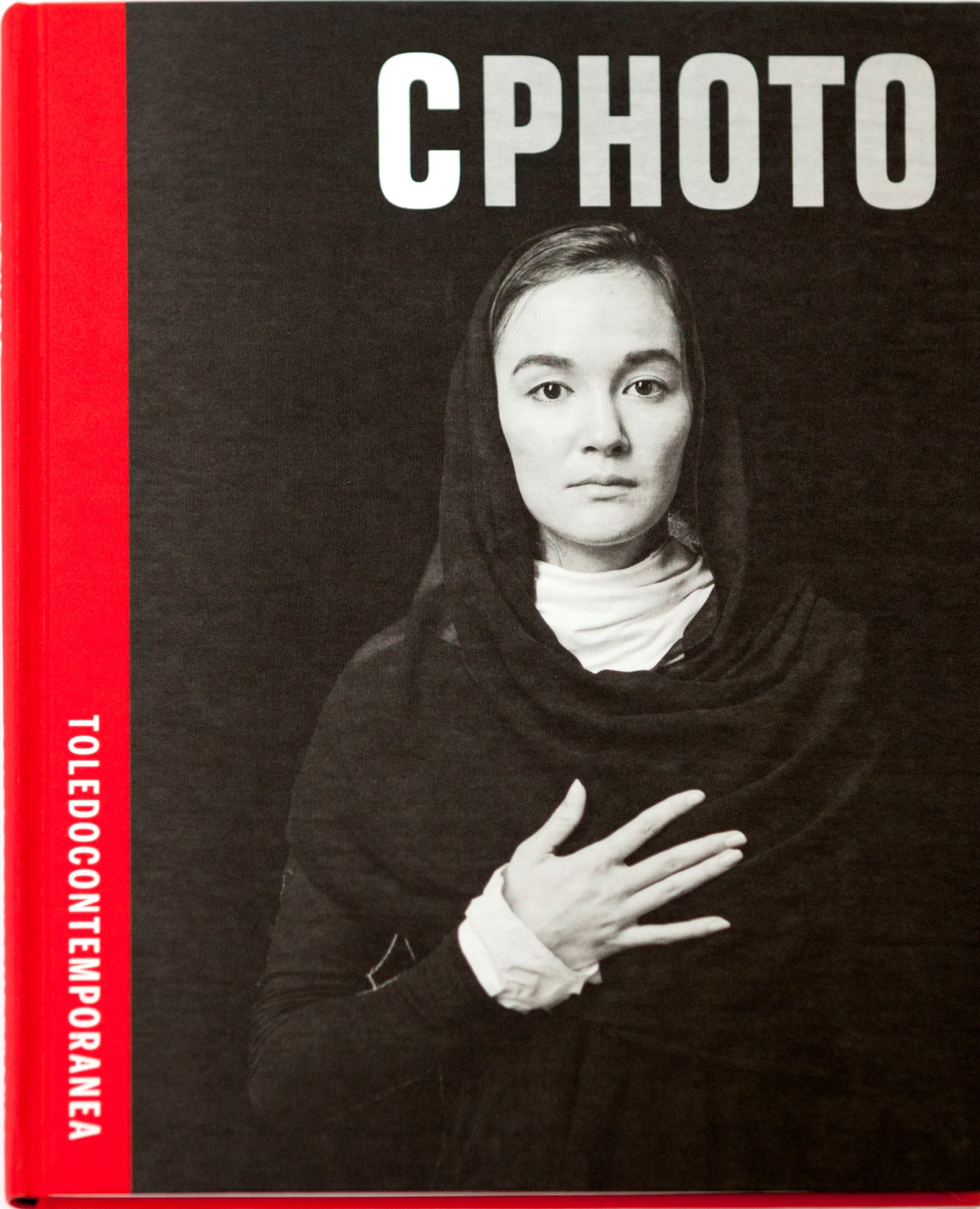

The Iranian artist Shirin Neshat dares to make a direct comparison with El Greco's figures. In her photographs, men and women adopt the same poses as the floating, selfless figures that pray in El Greco's paintings. In these photographs, the serenity, the eyes, the joint hands, the upwards gaze, the ascension to the Christian heaven or even the somewhat exaggerated size of the hands or the elongated bodies typical of El Greco's paintings, become tangible once again, fueled by a personal feeling.

Also influenced by the artist, Flore-aël Surun, however, rejects a direct comparison with his work. Nevertheless, one can perceive how she plays with the grace of the figures that are illuminated by a divine light in El Greco's paintings. She places the subjects of her portraits under a light that pours over them and makes them shine. Some figures appear more powerful, portrayed in a more subtle, colourful, ambivalent and everyday way. Others are placed under a cone of bright, almost sharp light that enthrals, captivates and defines them.

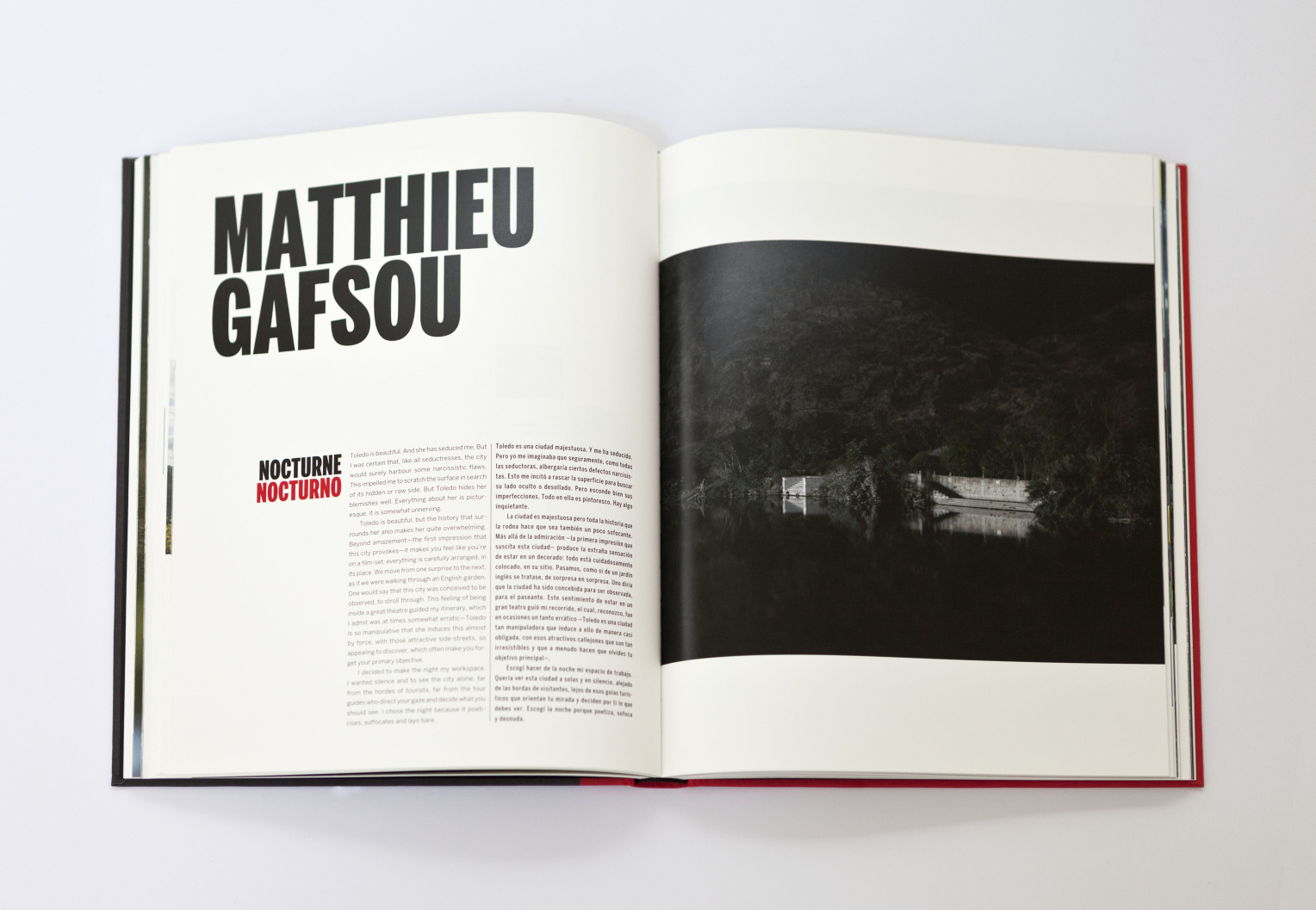

Toledo from afar, at night, from an angle: the work of Massimo Vitali, Matthieu Gafsou and Rinko Kawauchi seem to be avoiding, be it conscious or unconsciously, the historic quarter. Massimo Vitali, through paths visible from the nucleus to the outskirts, towards the landscapes, and back to the centre. Matthieu Gafsou, set on photographing only at nighttime, when the city is calm and empty and he can finally understand 'her'. Vitali draws attention to the interplay of the interior with the exterior, the contrast and the transition from noise to silence, from distance to nearness, from commotion to quietness, from order to chaos. Gafsou, in turn, creates mysterious moments. The jetty of the river, which shines in the darkness of night, is presented horizontally as if Romeo were waiting for Juliet, Tristan for Isolde, Catherine for Heathcliff, Orpheus for Eurydice or Cyrano for Roxanne or vice versa. Until the loved one's boat arrives, they emanate a secret that leads us to believe, as Cyrano said, that 'it is at night that faith in light is admirable'. With her unique point of view, Rinko Kawauchi, uses the cement landscape as an excuse and as an objective, to observe the forgotten corners of the city and capture the brilliant moments that are important to her. Her images are gathered under the title Land of Light. In them, she photographs magical and exclusive moments in which the delicate flashes of light transform the world. Clarity, moments of airy brightness, emissions of poetic light that raise the spirits of the observer and make us forget where we are, that allow us to dream of a benevolent world that feeds our soul.

David Maisel distances himself from the city even more than Vitali does: he raises himself above it but not in a hot air balloon (as Nadar did, for instance, in the first photographs ever taken) but in an exciting helicopter that flew over the city while Maisel glimpsed a city that encloses within its structures magical and hidden courtyards. Today, the visitor doesn't knock on the city's door: he lands right in the middle of it. Abstract Toledo.

On this occasion, Dionisio González's images don't focus on the suburbs or on favelas. Instead, they turn Toledo's historic quarter into an astonishing absurdity of modern architecture. He pierces, with his visual suggestions, the unity of a city that has been developed and immobilised for centuries, as if it had been attacked by missiles from above and below, simultaneously, as if a mine had exploded. He meddles in the city as if the reconstruction of the Alcázar, practically destroyed during the Civil War, hadn't been done in such a painstaking way but had been abandoned to neoliberalism. The image is so solid that with a single interference, and just like the artist says, all is in danger. González's two panoramic images are notable because they show us the city both intact and transformed. Through his interventions, he reflects the contrast between modern architectural designs and the aesthetics of powerful ancient constructions, destroying our expectations of unity and cohesion with his visual interludes.

Abelardo Morell has created his own paintings for ToledoContemporánea. He makes photographic tapestries in which he weaves together the sky and the ground, distance and closeness, needle and thread. Through a periscope, he allows his gaze to fall to the ground from a tent he has set up in different points of the city centre. The subjects and objects seem to come together once again in a new pictorial, almost abstract fabric that blends here and there, being and wanting, architecture, painting and photography just as he wishes it. Toledo becomes a carpet of images.

Finally, like Philip-Lorca diCorcia and artist Michal Rovner, who has created for ToledoContemporánea a visual theatre in collaboration with German composer Heiner Goebbels, Vik Muniz participates with a single work. While DiCorcia intertwines his work with eight images in the shape of a cross, Vik Muniz creates a single collage with thousands of photographic fragments, with the perspective of Toledo as its structure and with zippers that open to reveal what is hidden, what lies beneath the surface. Muniz makes use of El Greco's View of Toledo, painted between 1597 and 1599, to create an image that is, in a way, a superimposed template on which life continues in its variety and temporal dimension, as if we were viewing the current age through the lens of El Greco. While the use of colour in El Greco's work was dominated by light and tranquillity, View of Toledo, After El Greco seems to overflow with colour. Shreds of images are juxtaposed with fragments of discourses mixed with a savage and dense texture, with a living contemporary setting. The viewer begins to compare this vision of the current world with that of El Greco. Despairing and illuminating at the same time.

The artists that have participated in ToledoContemporánea faced a universe of meanings kept within the cities walls for centuries and covered, in the Modern Age, in images from the media that have been trampled, on occasion, by hordes of tourists. Among these meanings is the powerful figure of El Greco, whose rediscovery signified his own rebirth within the history of art.