A lush green field of dandelion clocks at the beginning of the book, a high flowery meadow yellowing slightly towards the top of the slope. A naked tree trunk supported by props cuts horizontally through the picture, and sheets, bath towels and bedside rugs flutter gently in the spring breeze, all orange except one towel, a rich, glowing orange laughing at the pale spring sky. At the end of the book, stiff, listless washing hanging up to dry, covered with fresh snow, the washing and the landscape – the sky itself dissolved into a diffuse white, the expansive, luxuriant colours frostily withdrawn into the gaudy, multi-coloured washing. The rest is white, serene and pure.

The book entitled "Rokytník" begins and ends with these pictures. Its cover, now closed, is of orange linen with gold-yellow lettering. Next to it on the table lies "inhabitants", smaller in size and printed on blue-grey paper, also with coloured lettering, but cooler, bluer. The first page continues with the theme of winter: a snowy day in Berlin's Alexanderplatz, but this time devoid of purity and freshness. Like dots of colour, scattered cars fight their way through the diffuse, veiled light and snowflakes, some of them stranded diagonally across the road, or moving slowly along, nose to tail. In the background, a little way away, the television tower reaches up into the misty light. Similar, in a way, is the shape of the sunflower at the end of the book. A deep blue base against a white wall, a plastic flower pot on a white saucer, with a bare, pale stalk projecting upwards like an antenna, bearing, to our amazement, a sunflower at its tip, a skewered, badly battered sun. The end. Golden, too, is the cover of "Vielsalm", the work commissioned for the Sunparks Art Project. Wisps of mist hang low on the trees in the first picture, sliding through a dense park landscape full of vibrant greens in various tones and shades. A morning mood? An early Belgian summer? The colours are fresh and vigorous. The book ends with a great outpouring of nature's energy, of light. The sunlight turns the autumnal colours of the fern into glowing, incandescent radiance. Potlatch before the decline, before the impending winter.

The beginning and the end. In "Female", too, Jitka Hanzlová's latest, serially conceived book with portraits of women: a cool, blue, winter-coated photograph is countered by a vivid T-shirted summer picture, with both women wearing berets. The beginning and the end are sedate and dignified, they endow the images with stability, giving the still, soft, unspectacular sequence of pictures firmness, and setting the mood. The theme of "Rokytník" is cyclic, with the change from summer to winter and the incorporation of human affairs in nature; in "inhabitants" there is a process of displacement, from the frosty cold and milky crossroads to nature, in a flower pot, trimmed almost to the point of self-denial; and in "Vielsalm" it is energic, from the satiated, awakening and gently simmering nature to the last great outpouring. Beginning and end, between them images that seem to suggest a story, a story that begins, breaks off, and furnishes fragments of isolated sentences. A story, light and volatile, unlinear, a field of tension marked out and contained by two poles. Nevertheless, this establishment of the beginning and the end entails an obligation: in spite of all its airy lightness, it leads us to suppose that this is a matter of life and death. A visual, conceptual space opens up between the beginning and the end, a space that tells of rootedness in nature and embodiment in everyday activities. And of the desire, the longing for this rootedness, and of its loss, society's and our own.

"Rokytník" and "inhabitants" are diametrically opposed to one another – countryside and town, village and everywhere, nowhere – and yet they emerge as strangely dovetailed experiences. Rokytník is Jitka Hanzlová's native village, a place in north Bohemia that she left early on because it was too cramped, because she wanted to sample the taste of a different and more mundane fruit. After her escape to the west she could not go back for eight long years, and then, in 1989, she rediscovered the village, saw it through new eyes, as a sporadic returnee, as a visitor and former inhabitant in one and the same person. And the town took on the aspect of a new and alien experience in the western Germany of the time, the town in general, its signals, structures, ways. A new space with a different rhythm, where time passes differently. The "staccato" of the city. A space for whose openness she had longed and to which she was now exposed. On the one hand there was the concrete, eloquent place, the village, the rootedness; on the other the abstraction of the city, not regionally bound up, everywhere, uprooted – contemporary urbanity, with no basic bond with nature. And then the reversal of the expectation: the experience of the apparently "open city" as an encapsulated, blocked-off structure, and the development of a defence against senseless hectic activity. ("I parked my memories and lived at half throttle"), and a new interest in the village that she had previously felt so constricting: in the breadth of its horizon, the value of slowness, the value of what used to be familiar and therefore of little worth. "It was my perception of people, nature and things that I had known that changed... Distance had enabled me to re-perceive stored experiences." The boy dancing with a white goat outside the village in "Rokytník" and the woman walking with the pedigree dog in the suburban public woods outside the town in "inhabitants" are similar and yet endlessly alien to one another – a beginning and an end, but also a simultaneity of contrasts in different places.

Jitka Hanzlová's photographs have the effect of visual statements. There, look, that's what the world is like, that's how it could be, but also different. Most of them are centrally composed, and they are all in vertical format: portrait format. Almost, one is tempted to say, stereotyped – before one's gaze is drawn into the picture, seduced by the light, the colours and the diagonal lines. Like small-format plates that show the world, quite simply, as it is – here, take a look at this. But then the simple, visual impression is transfigured and the first inklings of clear, descriptive meaning dissolve and the pictures are revealed as complex worlds. The photographer holds the images up to us, still and straight; there are no contorted camera angles, no artificial, subjectively generated perspectives. The photographs are structured by diagonals running from the bottom to the top, leading out of the picture or penetrating into the portrait format. The photographer's eye is always directed squarely at her subjects, while the background landscape moves away, approaches or remains – quite simply – still. The world opens up, paths lead to..., clouds gather and pass, hose pipes wind, snakelike, through the fields, and occasionally our gaze wanders into the distance, and the distant view congeals into an inner vision. The pictures breathe and hint at distant horizons – with the exception of the few interiors, for entrance to the inside is rare – in which the same diagonals trigger a feeling of oppression and constriction, in which space becomes a vacuum, a flat-pressed surface.

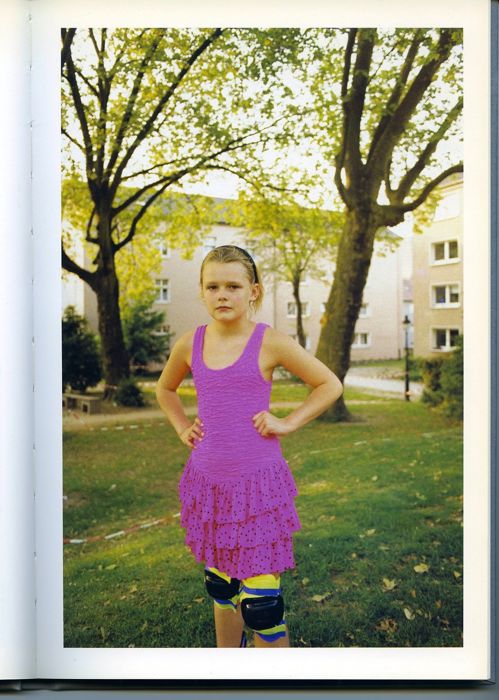

Not much happens in these pictures, most of them are still. The village inhabitants surrender to the scrutiny and look into the camera, at us. Three or four supine figures interrupt the consistency: a girl lying in a field, so flooded with light that we fancy we can smell the summer; two children crawling along the road, their naked bodies dabbing at the rainy surface, and a pig in an aura of light, its death still a symbol of possible union between man and nature. Something similar seems to be happening to the landscape in its largely unspectacular but sensuously tangible presentation: summer, winter, rich or singed green, damp, dry, blossoming or snow-covered. Yes, rich or singed green, three different shades of orange, two of lilac against a changing green, wine-red against grey and medium green. Rarely seen confrontations of colour, some of them scattered and blurred, non-colours, and concealment, with gentle or glowing light transfiguring the everyday scenes. Without any false romanticism, they whisper of stillness, of the course of events, of small delights. Documentary poetry, poetic documentation, but never playful, tending to be formally severe.

The interaction of forms, colours and light is also conspicuous in "inhabitants", but in a different way. The landscape seems to have been folded up, distance and depth are lacking, as are the dynamics of the diagonal; the horizon is covered over. Vision is impeded or falls to the ground, the world seems encapsulated by fragments of façades, almost imprisoned, blocked off, the right angle and the plane predominate. Our attention is caught by these planes, we discover a richness within them. The pictures are alive with the materials' own colours, the grey of a concrete floor, the pale green of floor tiles, oily rainbows of spilt petrol, the marble surface of a façade, white plaster, a spotted, violet dress, red hair. The light seems more uniform, more obtuse, only rarely does it transfigure an orange turban or the yellow foliage of the woods. Animals do not dance, they are tied up, kept on the lead or confined to cages, and human beings inhabit balconies.

“Cages”. But only in the intensification of our imagination. The photographs do no more than hint at them: space is enclosed by windowless façades, and fences, cages, parks and leads mutually disrupt and block the interaction between man and nature.

And once more a reversal of expectation, this time that of the observer: the town pictures are not filled with despair, they document a struggle, a fight: self-assertion, survival in confinement. It is only in comparison with the tangible, tactile, smelling, tasting surfaces in "Rokytník" that the materials in "inhabitants" seem so hard and cold, for in themselves they are contemporary and "normal". Nor are the "Rokytník" photographs idyllisations of village life, for we can sense a distance, a reserve; they are poetic visions of melancholy, of the dichotomy between a progressive and a self-abandoning era, the experience of the past in the present, the recognition of a different flow of life, of "stillness, slowness, day after day..."

All the quotations originate from Jitka Hanzlová