Giorgio Wolfensberger was born in Zürich in 1945, grew up in Winterthur and died in 2016 in Umbria, his adopted geographic and political home. Not only was he an industrial photographer, filmmaker and slide-show specialist, an expert on the Swiss modern dancer Suzanne Perrottet and an exceptional sleuth of archival photographs; he was by nature a photographer and collector imbued with a seventh sense for the things of this world. He seems to have exercised a magnetic pull on the peculiarities of everyday life, deviations from the rule, the play of objects, the humorous and the grotesque in the course of the world, as if his eyes, nose and fingers were probes tracking the minutiae of material reality. Whether putting together an exhibition or a book, roaming the city or driving around the countryside, he always managed to find something special in the ordinary, something personal in the general, something rich in the poor, something strange in the norm. His artistic photographs have been brought together for the first time in this book to form a veritable panopticon, a multifarious dance of things.

One was liable to underestimate Giorgio Wolfensberger, at least at first glance, when first struck by his gaunt figure, his narrow face framed by an unruly head of hair, his restless, searching eyes. But there was never much time to take a good look at the man because no sooner was he there than he was gone again. When expected, he didn't show. And when he did, he’d overwhelm you with his enthusiastic, slightly hectic conversation. Then he’d sneak off somewhat distractedly on his soft soles... and return with bagfuls of photographs he’d dug up in some archive, just the right pictures for an exhibition or a book we were working on for the Fotomuseum Winterthur, plus a couple of unlooked-for finds, surprises that would expand and enrich the initial concept. His lanky, gangly figure seemed to snake its way back and forth between Umbria and Switzerland, sometimes alone, but mostly with his wife Margarete. In conversation he might casually mention that he’d put out a book on Suzanne Perrottet, a pioneering pedagogue of expressive dance and movement, and was now working on a follow-up volume. That after his apprenticeship in industrial photography at Sulzer in Winterthur, he’d studied filmmaking, worked as a cameraman and put together diaporamas for the Umbrian authorities. And that he was painstakingly photographing all the flora of the Portofino region, including subspecies, related varieties and metamorphoses, to form a sort of photographic herbarium – an endless and arduous assignment that demanded tremendous perseverance.

Yes, Umbria, time and again. Città delle Pieve, the countryside, this farm that was home for a while to a menagerie of goats, chickens, geese, pigs and always donkeys, and for a while served as a successful rehab farm for drug addicts, and whose walls and rooms over the years became repositories and mainstays of a great many different collections. Giorgio (alias Jürg) Wolfensberger, was a semi-typical dropout of the 1968 generation. In the early ’70s, after a doctor advised him to take it easier, he turned his life upside down. He moved permanently to Umbria, earning his livelihood there and in Zürich, a little here, there and everywhere. At Becker Audiovisuals in Zürich he met Walter Keller, the founder of Der Alltag and Parkett magazines and, later on, Scalo publishing house. It was a formative encounter in more ways than one. Through Keller he discovered the photography of everyday life that would loom so large in his subsequent personal work. With Keller’s support, he began taking on professional assignments from the mostly left-leaning regional administrations in Umbria.

And I got to know him better through an exhibition and book project, Industriebild – Der Wirtschaftsraum Ostschweiz in Fotografien von 1870 bis heute (“A Picture of Industry: The Eastern Swiss Economic Area in Photographs from 1870 to the Present”). Giorgio initiated me into industrial photography in 1993–94, introducing me to the myriad occupations exercised within closed factory walls and providing me with what was probably the best, most diverse and most intensive training a photographer could get at the time. At the start of the exhibition, we curators wrote:

Switzerland has had a proud industrial era of its own. Hundreds of thousands of photographic records kept in company archives in Eastern Switzerland attest to spinning and weaving mills, embroidery shops, metalworking and engineering industries, the electrical, garment and food processing industries, and the construction of roads, railways, power stations and factories. These photographs, in the form of glass plates, blueprints or painstakingly produced prints, are stored in factory basements, some of them forgotten in shoeboxes, exposed to dust and humidity, some of them meticulously archived and chronologically arranged in photo albums. So far they have received little attention. And yet they’re an exceptional trove of national history, documenting every aspect of industry, the modernization of Switzerland, the innovative and productive power of then fledgling companies, working life in factories sealed off from the outside world, the prevailing mindsets in the various trades, social cohesion or clashes between labor and management, men’s and women’s work, industrial discipline and leisure-time pursuits. They also present some tremendous, monumental industrial buildings and machinery in Switzerland, an otherwise fragmented nation.

I owe much of what I now know about industrial photography to Giorgio Wolfensberger. We discussed at length the many different dimensions of industry, industrial photography and the industrial photographer. A highly realistic high-precision photograph of the physical world is often described as being “objective”, "documentary", "matter-of-fact", "neutral". Industrial photography, which took great pains to achieve precise, objective visualization, is a perfect example. And precisely because it was so precise, as well as wide-ranging in scope, training in photography at a large industrial company was once considered the most comprehensive and interesting photographic training of all. An industrial photographer had to portray blue- and white-collar workers entering the workforce and leaving it, i.e. at retirement. He had to document production marks and casting flaws, in other words to assess materials and products photographically. He should be capable of capturing a simple little object under lighting so perfectly calibrated that you could make out its materials and design – and of doing the same on a giant scale for, say, a giant cogwheel 10 to 14 meters in diameter. And he was an architectural photographer, too, taking pictures of huge factory buildings both inside and out. So his job involved visualizing all sorts of different things in all sorts of different ways, registering and inspecting materials, studying industrial processes, displaying and communicating the company’s accomplishments and its products, represented as objects that seemed to materialize out of the blue, shot against a white backdrop, wholly removed from the production context.

Whatever he shot, the industrial photographer – perhaps more than in any other branch of photography – had to stick to very specific guidelines: the photograph should be fine-grained, the lighting should make the tonal values balanced and logical, everything in the field of view should be in sharp focus and reproduced with minimal distortion! These four essentials became the industrial photographer’s credo. So he had to know all about film and how to use spotlights, mirrors and white paper to capture each object in just the right light. Undesirable reflections and refractions were averted by matting shiny metal parts. When developing film or making copies, he’d even out, soften up or intensify the negative, then retouch it with a scraping knife or very soft pencil to achieve the desired brilliance, density and detail of the lighter as well as darker parts of the image.

In other words, almost every trick in the book was used to produce the desired objectivity and visibility, to arrive at a sharp, highly detailed rendering that did justice to the object’s material qualities. The photographs were liberally “doctored” to yield a “neutral” reproduction. Hence the inherent paradox. Industrial photography was apparently not about straightforward visual documentation, but about elaborate pictorial constructs. Whether it was a matter of photographing each object like a magical manifestation ex nihilo against a blank white ground, or stylizing a workshop with its shiny machine parts as a locus of modernism, or portraying a row of welders in action like actors on stage in a play – they were always arranged, staged, and only then, after lengthy preparation, shot. Taking a picture was an event, a production unto itself. It became a tableau vivant, a still life or an "industry still", like a Hollywood movie still.

Discussions with Giorgio Wolfensberger gave rise to suchlike wide-ranging reflections. And this description of industrial photography points up the two sides of Giorgio Wolfensberger: his vast range of technical know-how in industrial photography – we can still see the blueprints he produced as an apprentice at Sulzer, the big industrial company in Winterthur – and his vast cultural knowledge of industry and photography in general. The second project we curated together was called Die Fotografendynastie Linck. Ein bürgerliches Sittenbild – Auftragsfotografie als Spiegel der Winterthurer und Zürcher Gesellschaft 1864 bis 1949 (“The Linck Dynasty of Photographers: A Genre Picture – Commissioned Photography as a Mirror of Winterthur and Zürich Society from 1864 to 1949"). Giorgio and his wife Margarete later researched in Switzerland and Italy for Im Rausch der Dinge – Vom funktionalen Objekt zum Fetisch in Fotografien des 20. Jahrhundert ("The Ecstasy of Things: From Functional Object to Fetish in 20th-Century Photography"), another project for the Fotomuseum Winterthur . This exhibition and book project transmuted the photography of industrial production into that of the product: the invention, development, production, advertising and sale of the product as well as its mutation into metaphor and fetish. It also provided a poignant look at Wolfensberger’s thinking and photography.

The exhibition (co-organised by Thomas Seelig) was about objects in our world and images of those objects. The English word "thing" originally derives from the Germanic legal term for the court (Old High German thing or ding, Middle High German and Middle Low German dinc), the assembly of free men. Nowadays, a "thing" carries less weighty significance, it’s merely an object. The point here is what an important institution, namely a court or assembly of free men, this little word “thing” (or “ding”) once denoted, and how reduced, how banal, its present-day meaning is. This gradual diminution of a word’s meaning is often observable in the evolution of a language – just as "vrouwe", which once meant a lady of standing, the “mistress” of the house, has devolved to ”Frau”, the "neutral" term for any adult female, regardless of her social standing.

But it also reflects a change in what things mean to us. Many objects in the Middle Ages were not merely useful, they were vital necessities. Let’s say an assembly of free men were trying the case of a stolen axe: then the thing, the court, would be deliberating on an object of vital importance to a man’s very existence. An axe, made by hand, was one of the few objects which accompanied a man his whole life long, and which even made his survival possible in the first place. Nowadays we’d be annoyed about the theft of such an item and promptly head over to the next hardware store to pick up a new axe – or rather a chainsaw, which is handier. Our relationship to functional objects, e.g. a computer, has become purely utilitarian, usually with little or no sentimental attachment. Reduced to its mere function, any object can be replaced at any time.

People have always been ambivalent about the world of manmade things. In the 20th century, especially in the last quarter thereof, our relationship to things changed fundamentally. The invaluable thing that was once vital to a man’s livelihood, even his survival, gave way to industrially manufactured things, to mass products. Mass production democratizes the possession of objects by making them affordable for many – but at a price, for they no longer evolve over time, they are no longer unique, cherished items, but must now replace a lost aura with the luster of novelty.

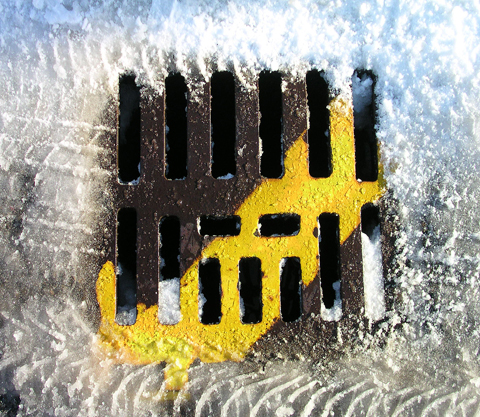

Wolfensberger immersed himself in researching The Ecstasy of Things, the follow-up to his Industriebild. It was all about his way of seeing the world. He was keenly intrigued by how we human beings construct our world, how we plan, execute and set it up, and how it then takes on a life of its own, how individual elements, things, become important, even famous or infamous, then gradually rot or rust, are displaced, dissolve and take on very different meanings. His approach to the world might be compared to cutting off the top half of all the letters in a sentence and having to guess from the lower half what the sentence once said and what ultimately became of that. We owe this truncation, this transformation, this disappearance, to the ravages of time, to the use, wear and tear, and repurposing of things. This truncation frees the thing from its utility and transforms it into an object of poetry, art, visual humor – elements we discover in many of his photographs.

Some portraits of Giorgio show him forming a frame with the fingers of both hands and peering at the world through it. He was seldom more concentrated than when contemplating the world, seldom more absorbed than when taking aim, focusing and firing, or scrutinizing the finished photograph as an excerpt from the world, as an emblem of our built environment, our ordered and unordered world. Wolfensberger hardly ever showed any interest in the newly constructed world, for his attention was riveted on the world already in use. An inhabited house. A rutted road. A broken signpost. Glass panes smeared with graffiti. A rickety old mailbox and faded, peeling lettering on the front of a building, an overlooked and forgotten pedestal, a painted trail blaze, architecture that looked curious, strange, when viewed from an unusual angle.

Pictures always speak a language of their own, eliciting different discourse from our physical experience of architecture, of the built world, the urban texture, the world of three-dimensional objects. Photography transforms volume into surface, distils matter into shapes and signs. It accentuates, distorts, enlarges or reduces it, glorifies or degrades it, but hardly ever leaves the world alone. Images of a used and chipped, transformed, reformed and repurposed world – the world in use, trousers in use, as Roland Barthes puts it – deform a second time things that are already deformed, using use to transform the world into an “empire of signs”, of merry, droll, sometimes pensive, melancholy, signs.

With the exception of his early black-and-white Italian photographs, Wolfensberger’s world is often devoid of human beings. It’s a world of things, objects, the world in use that reflects human agency, the fallout of use, traffic, neglect, or pointed verbal or pictorial commentary scribbled or spray-painted on a wall. Giorgio Wolfensberger enveloped all his subjects – things urban and rural alike, natural and artificial, built and written, human and animal, male and female, weighty and commonplace, as well as regulations and scrawlings, street art and graffiti – in the same earnestness, the selfsame subtle tongue-in-cheek humor and the same equanimity. He hardly ever resorted to the device and tone of sarcasm. His photographs turn three-dimensional reality into a two-dimensional surface, a blotter that absorbs all the signs of the perceived world and places them side by side, in familiar or unfamiliar ways, on the same plane, in little three-line haikus, succinct remarks, observations, a slightly arched eyebrow, an unexpected and surprising juxtaposition. He played nimbly on the keyboard of the famously absurd simile used by the poet Lautréamont – and taken up by the Surrealists – to describe the beauty of a young man: "He is as beautiful as the chance meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table!” Wolfensberger transformed matter into signs in his world view, distilling the humus of his pictures out of the banality of the surrounding world. In his photographic fingers, all things congeal into a photographic text, a sort of visual alphabet of the quotidian, of everyday living and working and adjusting and dying. Where each photograph was shot is ultimately irrelevant. He removes his photography from all reportorial reference and localization – where? when? what? – by transforming the signs of reality into little showpieces. Almost the only visible chronology in his work is the evolution of technology from the large-format camera, the view camera, to the Leica, followed by the first small cheap digital camera that was to be the constant companion of his final years, even though the amount of data it could hold was miniscule by present-day standards.

His photographic phenomenology of the world of utility, of the poor used object, is as much a carpe diem as it is a memento mori. Life-affirming in every square inch of its frame, and yet much alive to the mortality of all things, all life. Like a light-footed, slender, agile dancer, Giorgio Wolfensberger tiptoes among the relics, the living, talking vestiges of the world and offers up his merry, sometimes melancholy, pictorial commentary. A photographic phenomenologist of everyday life, of the here and now, repeatedly gazing at the tips of his own toes to hint at his own existence, at the partiality, the subjectivity, of his ironic gaze, as he ambles or drives by, attentively, with an unflagging love for life, for the world – even as he observed, in the Castagnara series, the gradual dilapidation of a house on the opposite slope over the course of his life.

Thank you, Giorgio, for this dance of things in the rich realm of your pictures.