In the mid 1960s, the first live transmissions of footage of the Vietnam War announced what the continuous live coverage of the Romanian Revolution and the ban on press photography during the Gulf War would later confirm: photography had relinquished its information mandate to television. Television was consistently faster than photography in presenting an event—regardless of its scale or scope—to the audience. Each evening, the TV news would inform viewers of the headlines that would appear in the following day’s newspapers and next week’s magazines. This heralded the end of the great era of photojournalism. The time had come to say goodbye to the Capas, Cartier-Bressons, Bischofs, and McCullins, to the immediacy and intensity of their images of war and to their sensitively, carefully framed portraits of life and death, of the violence and injustice of this world. Although magazines began to employ shocking images as weapons to counter the temporal advantage of television and the allure of advertising during the 1980s, this shift could not be halted. Even the digitalisation of images and their dissemination via the Internet (which allowed photography to regain the upper hand in terms of the speed with which it could reach its audience) could not turn the tide. Instead, those factors eroded the power of rigorous photojournalism, documentary photography, and the photo essay. Today, photographs can be obtained for free: anyone can snap away, no effort is properly remunerated. As viewers, we must ask ourselves: When did we last see a published photograph that really moved us? Have we ever said, after looking at a photograph, “We have to do something to change this situation”? This enlightened attitude had always been part of photojournalists’ credo. Have we perhaps oversaturated the world with images?

At the beginning of the 1930s, however, everything was different. The illustrated press was at its zenith. Invented and developed during the nineteenth century as a short, visual parallel to the novella or bourgeois novel, it proved victorious in the 1920s thanks to a number of innovations: high-speed printing, rotary printing, halftone printing, and two-colour, then multicolour, printing. In Germany, pioneering publications included the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung and the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, each issue of which was printed in editions of over 500,000 copies. In the 1930s, a new form of storytelling developed, with lots of photographs and accompanying text, first in Europe and then in the US. At the same time, Leica revolutionised the way photographers worked. Oskar Barnack had invented the first Leica in 1914; in 1925 the Leica I went into serial production and was presented at the Leipzig Spring Exhibition. The real breakthrough, however, came in 1932 with the Leica II, which had an integrated rangefinder and interchangeable lenses. Photography became immediately practical, lightweight, agile, dynamic; it lost its stand-reliant stiffness, with the eye-level as the benchmark. From then on it became possible to travel the entire world and report from anywhere, with fast, versatile, and lively results. Pioneers of social documentary photojournalism, including Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, were soon followed by many successors. To this day, Erich Salomon, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Germaine Krull, Margaret Bourke-White, Werner Bischof, and Robert Capa remain some of the world’s most famous photojournalists; Picture Post, Paris Match, Life, Sports Illustrated, The Daily Mirror, and The Daily Graphic are still considered some of the most famous magazines of the time. For a couple of decades, the entire world could be presented every week in the pages of illustrated periodicals and magazines with enthralling, extensive photospreads.

W. Eugene Smith was born in Wichita, Kansas, in 1918. At the age of 16 he began to take and publish photographs. After his father’s tragic suicide, he studied photography at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, dropped out after one year, moved to New York, and began work as a freelancer for the Black Star Agency, through which he worked for Collier’s, Parade, Time, Fortune, Look, Life, and many other important American magazines. In 1944 he began work as a war correspondent for Life and was seriously wounded in Japan. From 1947 to 1954, he worked for the magazine full-time. In these few years, he came to be considered, along with Margaret Bourke-White, as one of the real heroes of photojournalism and the photographic essay. Country Doctor, Life without Germs, Spanish Village, Nurse Midwife, Charlie Chaplin at Work, Reign of Chemistry, and Man of Mercy remain to this day some of the most important works of photojournalism to be published in a magazine. Sequences of photographs that aimed to convey a message, that wanted to communicate the essence of a story , eventually accompanied by captions or supplemented by text: Smith’s photographs went far beyond what was expected of photojournalism. His photographs were dark, sometimes almost gloomy, highly charged. Rather than aiming to describe the world, they wanted to incorporate it; rather than trying to produce a copy of it, they wanted to bring it to life.

In his essay Pietà: W. Eugene Smith, art historian John Berger examines Smith’s conflicted relationship with his strong, rebellious, and highly religious mother and its impact on his work, on his approach to the world, and on his search for truth in things. “His attitude to words, music, and his own art was essentially religious. He saw art as a means of redemption. Music and words were to him an accompaniment to the drama of looking for goodness. His own photography constituted his way of looking for this, his search. He was not a cultivated man for this implies belonging to a privileged culture. He was a loner. He sought a truth which, by its nature, was not evident. It was waiting to be revealed by him and him alone. He wanted his images to convert so that the spectator might see beyond the lies, the vanity, the illusions of everyday life.” Berger also wrote: “His unique use of black and white was intimately tied to his sense of vocation. Through blackness he makes the world his own—turns it into a dark, terrible, moral theatre where souls search for beauty or redemption. [...] Black, for Smith, was the valley of the shadow of death. Light was hope.”[i]

At the height of his fame as a magazine photographer, after working full-time for Life for seven years (followed by a few more years of commissioned projects), Smith left the magazine on bad terms in 1954. He was reportedly a difficult artist, a complicated, complex person to deal with: he never finished a commission on time, he was never satisfied with the layout of his images, with the graphic design, with the quality of the reproductions of his photographs, the captions, the entire presentation of the story. He freed himself from the restrictions of commissioned work and dependent employment, and began instead to look for greater depth and authenticity, driven by his desire to seek out absolute truths, to be fully present and prepared during the rare moments in which the truth of life manifests itself in worldly phenomena.

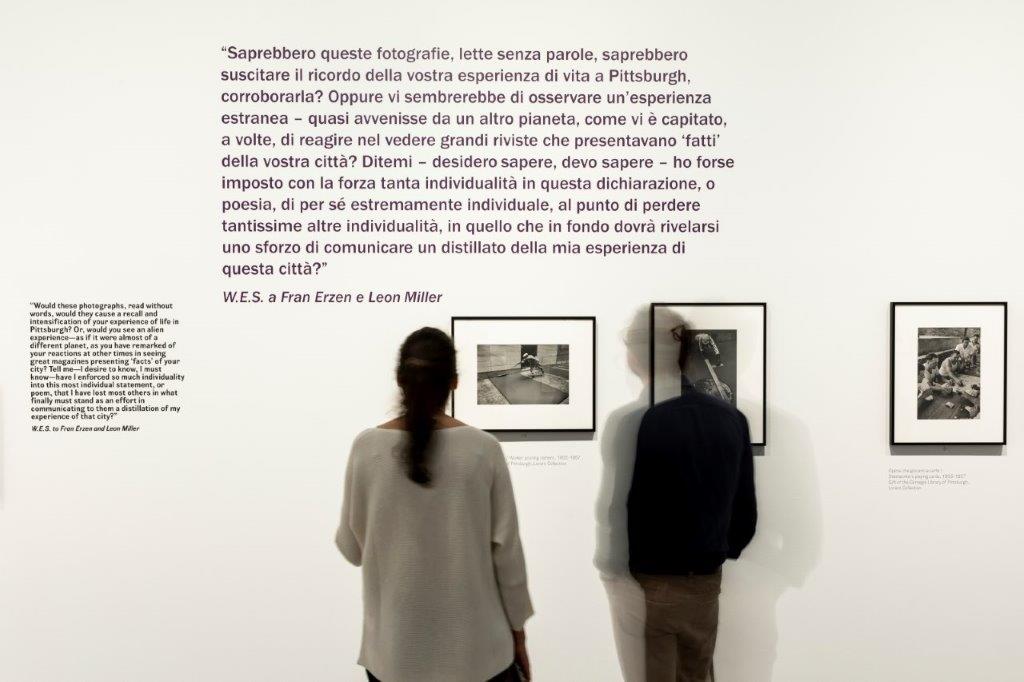

This break with the press, the magazines, and the media initiated a new chapter in his life. Ultimately it was also a break with his family, with his wife Carmen Martinez and their four children. Smith found himself at a crucial professional and personal crossroads. Having sold his house in Croton-on-Hudson in New York State, he moved to New York City, where he acquired a studio above a jazz loft on Sixth Avenue and 20th Street, in what was then Manhattan's Flower District. That same year he received a commission to take eighty to 100 photos of the city of Pittsburgh over six to eight weeks. This commission gradually became his major life's work, and ultimately a painful disaster. Instead of shooting for six weeks, he took photographs for two or three years, then spent the rest of his life struggling with the almost 20,000 negatives and 2,000 master prints, doggedly pursuing his ultimate ambition: to create the definitive book on Pittsburgh, the most famous industrial city of the first half of the twentieth century, and to capture the culture, the people, the workers, and the soul of the City of Steel, this town in the southwest of Pennsylvania, at the convergence of the Monogahela and Allegheny rivers with the Ohio River.

Smith’s failure was due to the impossibly high standards he set for himself. He wanted to convey the absolute, the entire truth of life—heaven and earth, light and shadow—through the ephemeral happenings of the city. Stephan Lorant, who commissioned the work, waited two long years for the photographs. Life offered Smith $13,000 for the rights to run the full story, but he refused. Finally, Smith managed to obtain thirty-six pages in the small-format publication Photography Annual 1959 and attempted to make the best out of the situation, presenting his photographs under the title of Pittsburgh: W. Eugene Smith’s Monumental Poem to a City. He failed miserably. Shortly before his death in 1978, he donated his archives to the newly founded Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona. They comprise tens of thousands of negatives, thousands of prints, his letters, his entire written notes, and around 4,500 tapes recorded in his New York loft. In addition to this huge archive, there are almost 600 prints of Pittsburgh in the collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art. It is from this collection that we have created the exhibition at MAST.

W. Eugene Smith wrestled with the representation of the absolute. Rather than merely documenting the world, people, life, he wanted, at least in some photographs, to grasp, to capture the very essence of human existence. Referring to The Wake in the Spanish Village, a vigil at the bed of a dead man, and the Pietà—perhaps the most brilliant black-and-white photograph ever taken, showing a mother with her daughter, her body utterly mutilated by the mercury poisoning of the sea in Minamata, Japan—John Berger demonstrates how Smith combines and contrasts the horizontal with the vertical: the victim with the perpetrator, the dead with the living, love with hate, the deceased Jesus with the resurrected Jesus. “Finally we come to the fulcrum of his genius. He accepted his mother’s sombre, condemning view of the world but he judged it far less harshly than she did because he turned the love that he knew through her into a principle to be searched for wherever he went. Love is always, amongst other things, pity. This is the love of the vertical figure. The love of the mourner and the healer; the love of the survivor for the departed.”[ii]

We have to thank W. Eugene Smith for giving us one of the most magnificent portraits of a city and some of the most humane photographs ever, even though he spent twenty years of his life wrestling in vain with the passage from representation to the black square (like that of Malevich), from image to relic, from the ephemeral to truth. In the history of photography, no one since Smith has striven with such agonising vehemence: he did not want a representation of blood, he was searching for blood.

[i] John Berger, “Pietà: W. Eugene Smith” in The Big Book (Austin: University of Texas Press with the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, 2013).

[ii] Ibid.