The photographic discourse in this book is entitled "New Europe". A bold assertion. Not one made by Paul Graham, but one that enjoys currency in his time, our time - as it has for the people of this continent at various stages in their history. New Europe. Unfamiliar as a prospect, though familiar as an aspiration. Only words, but at times loaded with such distinctly different implications. Yesterday, with very ambitious and morbidly egotistical intentions, Hitler brought into the world the most horrific attempt at implementation of the ideal. Today and for the future it is a concept to be flirted with rather than embraced by the European Community, as much as these times of broken illusions permit.

Hitler combined the idea of a "New Europe" with his plan for a "Nation Europa" under his rule - this being the name of a National Socialist propaganda magazine in the guise of a respectable journal, aimed at the elite of every Western European nation, who were to be defeated and their territories occupied. This elite was to be "enlightened" and enlisted as privileged auxiliary troops of the Reich, subordinate, and yet still assigned a higher position than the Slavs, Poles and Russians, condemned in turn to a life of slavery. Hitler's crazed idea failed in the end because he disregarded the fact that the nations of Europe were formed from a number of smaller constituent parts. Each was not in fact comprised of only one territory, one culture and one language, but they still emerged into the 20th century, formed steadily from their individual cultural groups (while other regional groups were gradually suppressed) and they were not to be destroyed overnight in a single conflict, to be swallowed up by an all encompassing Grand European Nation. The incomprehensible horror of Hitler's effort is anticipated in the lines written by Rabbi Jacob Schullmann, before he died in 1944 in the gas chambers of Chelmno:

"Horror, horror, man shed thy clothes,

Cover thy head in ashes,

Run in the streets and dance in thy madness

I am so weary that my pen can no longer write, Creator of the universe, help us."

(from "Shoal'", the documentary film by Claude Lanzman, 1974-85)

The current impulse towards a "New Europe" shies away from using the term earnestly again. It has become more pragmatic. The notion of a European spirit is again heralded, but the goal of the present century, indeed of the millenium, seems to be "Currency Union" achieved through the "Single Market Economy". The Ecu as the anaemic standard of a world where money takes precedence over spirit. And because, even for this, strength and trust seem to be lacking, the way forward and the speed and rhythm of the execution is submitted to the logic of computer programs. Everything happens automatically, at a predetermined time, even if someone should blast the machine into the air. Is this the European freedom at the end of the millenium?

"Everywhere, where the European spirit dominates, what is apparent is a maximum of needs, a maximum of work, a maximum of capital, a maximum of relations and exchange. This ensemble of maxima is what defines Europe, or the picture of Europe."

(Paul Valéry, La crise de l'esprit)

Paul Valéry had defined the crisis of the spirit and the ensemble of European "idées fixes" a long time ago. Will this new venture end in horror too? We are already experiencing unexpected symptoms and, paradoxically enough, from our individual retreats, still plead the cause of the great union as the only possible guarantee against dissipation and demarcation. Two years ago we were still unwaveringly convinced that the "Californian Dream" (George Steiner), the infinite capitalised lightness of being, would be fulfilled in Europe before the end of the millenium, after which Europe would go to the ruin engendered by its own consumption.

Today we are not at the point of a repetition, rather at the point of realisation of a seemingly archaic history, one which we believed to have long overcome, or at least to have got under control on the psychologist's couch, both on the individual and the social level.

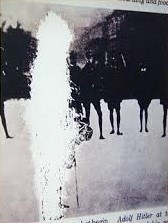

Paul Graham's large-scale colour photography work is situated in this context. Ostensibly the journeys Of 1988, 1989 and 1990 led him through nine West European countries: through Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, Holland, England and Northern Ireland. The narrative leads us past various references to historical events: the star of David for example, scratched in and scratched through again; or the Hofbräuhaus in Munich, where the Nazis often met early on; the Photographic memorial display in Holland, from which the Hitler figure has been scratched out; the Pilsner beer, introduced into Italy in the thirties as Italo Pils; the couple reflected in the disco ceiling mirror, reminiscent of Mussolini and his mistress, both hung by their feet; Franco's grave, spat upon and mocked; coins with the Generalissimo's likeness as thoughtlessly discarded as burning cigarettes by video games; the train coupling, taken in Drancy, which, like the toy train reminds us of the deportations from France; the park bench in Belfast, which tells of better times, the word "religion" written into the grafitti strewn surface of a telephone table in an employment exchange in Belfast; and finally the simple square hole, left behind by a post from the Berlin wall.

These signs are not in themselves a reference to the past, much more they alert our awareness, our memory. They do not look back, but manifest history, show how we deal with it today, how it casts a shadow on daily life, sometimes going almost unrecognised, sometimes violently disputed, occasionally even trivialised, ending up as children's toys. It is history exposed where it is thrust from the depths of time to the surface, whether we stumble over its gravestone, heedlessly walk away or contemptuously spit on it.

In between are placed images of people of today. Pictures of immersion, of escape, into music, into alcohol, into cigarette and drug addiction, the kick of ecstasy. Pictures of universal consumption, the commercialisation of sex and friendship. Pictures of isolation, of the one from the other, pictures of the screamingly colourful, grey daily life of today. Together with the traces of history a portrait of contemporary social reality is formed, unfolding a topography of presence, a social and psychological landscape, the traces of which extend over the lonely indifferent faces, in the nervous gestures, in attitudes altogether defeated, which makes even a park bench seem meaningful, surrounded by the horrible laughter of emptied perspectives.

"I wanted to make images about the bland grey promise of consumption led culture, the rush to the market that dominates everything. whose embrace we must accept or be expelled to the margin." Even more distant history is commercialised: the "angel" sits by the till in the department store, "Maria" is hopelessly isolated and hopelessly thoughtful, the "Jesus child" has just been overfed with the spoon. The word "religion", scrawled in doubt or affirmation, reflects the tragedy of the Northern Irish conflict, and the confusions that surround the issues at its core. Symbols of the deregulation of all values. as a rule sacrificed to the possibility of commercialisation. Graham's interest focuses on the point of intersection of the vertical diachronic axis, along which the present becomes comprehensible, and the horizontal, synchronic axis, without which history - inheritance - remains limited or indeed immaterial. He emphasises the permeation of past and present, and shows us the pictures of today's “state of mind”, of the state of our consciousness, of our spirit at the end of the century.

"And I will show you something different. begins the quotation from T. S. Eliot's famous poem “The Waste Land". The war veteran bares his upper body and reveals his wounds, whilst he looks down from the high ground to the edge of a Southern city. Graham shows us a wounded, battered Europe, a spiritual "wasteland". History, though often trivialised as in the case of the toy soldiers in the second photograph, marks out the framework, even forms the shadows, from whose darkness the events of the present emerge, and the light in whose glare the present seems small, grey and banal, but in its own shadows finds itself.

“I will show you fear in a handful of dust." In these pictures Graham stands watch, as the party of the eighties, a period abandoned to laissez faire, continues in full flow. In the dust of Friedrichstrasse station, in the reflection of the flames of German unity, the shadows of the past are watching, as silent as the grave. History, Europe today, in the mirror of its Falangist, Fascist and Nazi past - invokes the image of a cleverly constructed, impasto of history painting. Graham's photographs however are the absolute opposite; no totality, no uniform meaning, but fragments, the series of isolated elements as signs of history, as stations encountered by a thoughtful traveller on a journey through a present loaded with history. Fragments, enlarged to function as a physical experience, images as dominant, but also as simple and as matter-of-fact as a signpost, the colour fields sometimes as expansive and as monochrome as an enamelled trade sign. The hint of the great themes, the hymn, the pathos but nothing more. Not even the tuning up of the orchestra. Then it goes further.

The weightier themes are not to be found on the wider political level, nor in the realm of gestures poignant with history. The secret main themes, which bestow on this work so many surprises as well as density and complexity, are established on a more profound stratum, on a structural and morphological level. Take, for example - in the book one after another, as exhibits in the form of a triptych - the picture of a large-surfaced, orange-coloured, riveted iron girder into which is scratched the aforementioned star of David. To the left is the smaller picture of a man, dressed in late sixties/early seventies style - orange-brown leather jacket, leather shoulder bag, jeans - awkwardly protecting himself from the natural light. Shading his eyes, does he also shade himself against other influences? To the right, even smaller in format, is a girl of the eighties, who, eyes closed, seems completely mesmerised by the light and sound level. Next photo: the picture of a bolted, almost barricaded door in a poorer London quarter. Following is a triptych, with the display photograph of the rubbed out Hitler and the blood stain remover in the clean bathroom. Both are combined with the dense picture in the Munich Hoibräuhaus. A man in traditional costume is busy drinking beer and smoking at the same time. On his left a man wearing foggy pebble glass spectacles. In the foreground, bottom left, an ash blond "blind spot".

Beyond their specific spatio-temporal identification the pictures tell of a general disparity, of light, of glances, of possible insight, if one only wants, if one is only prepared to see, prepared to recognise and to understand. If the will can be summoned to really look at things, even the unpleasant, the painful, to look at people, even others, properly in the face. And with it, the contrasting attitude of looking away, of evading, of disengaging. Dim down the light, dim down everything that could hurt, drown, numb, anaesthetics with beer, addiction, music. Cut off, protect, wipe away, shut out, indulge, get drunk, stupefy. Insight versus stupefication. The here and now versus an elsewhere for anything that is unpleasant.

To go on, a floor strewn with used tissues in a sex video shop, sprays of blood on a white tiled wall, spit on Franco's grave, someone inserting a syringe into his arm, a dark hole left behind by a post from the former Berlin Wall, a doorway coordinated grey on grey. A tunnel of dreadfulness. These pictures, as also the nervous lacing of fingers, the smoking, the injecting, the overeating, the blinking, manifest a condition of heightened critical awareness. Inner tension, individual as well as socio-psychic instability grows. In between, in the middle of the book, the picture of a park bench — built of cement and stone — arresting one's attention. However, one sits there alone, watching, as the square gradually becomes overgrown and wild, without people finding each other there. Lastly this man. who lies on a bed and watches television, surrounded by the wildest colour patterns and tones. A picture suggesting the utmost privacy, the utmost relaxation and satisfaction and at the same time embodying contemporary inertia. Oversatiated with colours, overwhelmed by information, fragments. not knowledge or understanding. A (Western) world at bursting point. As exhibited work, this photograph hangs beside the dark picture of concrete slabs, concrete out of which pieces of straw protrude. A harsher contrast is hardly imaginable. Concrete, society's building material, manufactured from individual pieces of straw. As individuals dedicated to the illusion of great freedom are inexorably woven into the cloth of society.

The pictures and their arrangement are unsettling. False wall? Or real wall with false materials? With wood and brick imitations in plastic. False information? False promises under a blue sky, in full colour and finished in a high gloss? A picture of the most intimate, fervent passion? Or again only an agitated meeting of two business colleagues? Graham's photographs are also formally unsettling. Often fleeting, precariously balanced, out of array, out of true, out of harmony, even if, in an attempt to avert design artistry, their subject is for once plonked in the middle. There it is! Visible and sufficiently complex! Graham shows what he sees, directly and without nourishes, even sometimes appearing almost banal. Without discernible "photo-graphics", without that master-photographer style. One always looks at the picture, at its images, and not at the photograph as photography. The picture emerges before our eyes, physically, directly, without glass or frame, interwoven with the other pictures as a visual prose poem.

The historical references set the outer frame, images which break out of the confinement of photography, expanding in the mind of the viewer. The density of his picture world is generated by these morphemes, these single elements, which shatter the calm. Hard edged photography and nothing but. Here and there the legend provides the required topographical information, a story is told, and a single picture becomes a manifestation of history. As when Graham provides the additional information that the war veteran exhibits his wounds in a gay cruising area, when he confirms that it is whores and pimps who intimately embrace, when he reveals that at the easternmost point of West Berlin he had to photograph secretly, hidden, "from the hip", and that the toy railway cars, in their macabre overlay of form and content, are reminiscent of the children's deportations from France. Children! Lengths the German National Socialists would not have gone to. Make a note of that. It has become a work about seeing, in times of freely chosen short-sightedness. A work about reflection, in times of stupidity. A work about time and history, in times of seemingly timeless youth. It is a work against the peddling (or rubbishing) of all values — without finding fresh ones, without finding a new ideology. Graham's approach is in the best sense modern, which here means thoughtfully enlightening. As in "Beyond Caring", his book about the English Social Service, as in "Troubled Land", his landscape photography work in Northern Ireland. Not the attitude, only the form has at times changed slightly, adapting to each particular conception. Be it the seductive beauty of the idyllic landscape pictures, which draw us into the theme of the English-Irish, Protestant-Catholic conflict, or as here the seduction of the large surface colours, a partly mysterious presence combined with clearer, sometimes painful signifiers — all of which promote interest in the picture and its discussion.

"They don't need any perfecting, they're just fine... nothing could be any clearer." So it is said of the "miracle glasses" in the Günter Grass quotation. This may also apply to this photowork as far as its approach and conception are concerned. But pictures are and must be more ambivalent, must disturb, worry, without prompting an automatic confirmatory response from the viewer. This Graham understands, and for precisely this reason his multinational journey encourages the thoughtful response.