In the 19th century, the portrait resembled a small, private stage play. The subject of the portrait got ready, dressed appropriately, and set off to the photographer’s. Once there, he entered the studio—which, with its plethora of props and necessary items such as chairs, armchairs, drapes, pictures and statuettes was reminiscent of a small stage—and was fitted into this grid of accessories. The background and furnishings were chosen, the pose and attitude rehearsed—“Wouldn’t you like to be holding a book in your hands?”—and finally the lighting was set up. These were usually daylight studios because it was not possible to produce sufficiently bright artificial light. Blinds were rolled up or down over the windows and skylights until there was enough light on the “object” to be photographed—though avoiding a dazzling effect—and the modelling of the figure by the light produced the desired result. Finally, auxiliary objects were acquired: footstools, headrests and supports for the hands, according to the position of the sitter. These “tools” were necessary since the light-sensitivity of the film was still limited, and the exposure usually lasted around 30 seconds (in very early photography it was as long as 20-30 minutes). During this time the sitters had to remain absolutely still. They usually moved a tiny bit, however, much to the photographer's chagrin, and when the “freezing" was not completely successful, a trace of the passage of time could be seen on the print. Nowadays, we value this minimal blur of motion and regard it as adding depth to the portrait.

The subject of the portrait set out to acquire a picture that resembled him, and that complied as closely as possible with the image he had of himself and his social status. Depending on the ideas of the photographer and his subject, the result was a more or less private or public picture; a picture that focused on the appearance of the figure as such, or that emphasised his status in bourgeois society. Eventually, unless the photograph was unsuccessful, the sitter acquired a representative portrait, and one that looked like him. Before photography endowed portraiture with a certain authority, it was quite possible to produce a portrait of a nobleman or a monarch with features that, although they conformed to the idea of power, in no way resembled the sitter. This symbolic procedure was particularly evident in sculpture. The only thing that we can be sure of in the case of a bust of Julius Caesar, for example, is that it shows the light in which the ruler Julius Caesar was regarded. We have no way of knowing whether he really looked like that or not (the only way, of course, would be if a death masked had been made). Photography changed all that. A photo of Baudelaire taken by Nadar was so like him that we would probably have been able to recognise him on the street, even though the photo shows him as a thinker and a dandy rather than a private person; a mixture of the way in which both Baudelaire and Nadar saw “Baudelaire”.

Thus we are in the middle of a play. The “director” tells the “actor” how to move, where to stand, how to speak and, ideally, tries to bring out what is inherent in his character. It is almost impossible to think of the 19th-century portrait in any other way. This was photographic theatre in the service of bourgeois representation—democratic, because increasingly reasonable in price—an early form of photo performance similar to what reappeared much later, at the beginning of the 1970s: a photographic production.

The 20th century continued with this kind of photography for christenings, confirmations or weddings—ceremonial occasions in the course of a bourgeois life recorded according to their importance—or for photographs commissioned for a specific function, for example, in a severely reduced form, for identification or passport photos. But apart from this, it became increasingly interested in the snatched, unnoticed, "stolen" portrait. The research into circumstantial evidence developed in the 19th century was applied simultaneously to areas as different as the identification of historical works of art, the detection of crime, and the exposure of concealed layers of consciousness in psychoanalysis (see Carlo Ginzburg: Spurensicherung. Die Wissenschaft auf der Suche nach sich selbst, Berlin 2002). Now the subject of the portrait was not supposed to notice that he was being photographed. He had to be caught at an unguarded moment, when he believed himself to be unobserved, betrayed by a significant act, a meaningful gesture; for example a kiss, leaving a hotel, lost in thought, or preparing his toilet. Only in this way, it was thought, was it possible to produce a portrait that, even if it was not strictly speaking “true”, was authentic and definitely not theatrically produced; and only in this way was it possible to reveal the other, real face behind the assumed expression. This is particularly evident in the photographs taken by private detectives: each clandestine “portrait” of the person under surveillance is a part of the circumstantial evidence, a piece of a jigsaw puzzle that, when fitted together with other photographs, reveals the true story of the person being shadowed.

In other words, photography drew closer and closer to the person portrayed. It disregarded the medium distance of the studio portrait, it moved purposefully and somewhat menacingly in on its subject. Photography became more aggressive, more pornographic and overstepped its previously rigid limits. Nowadays, photography comes so close that, were it a person, we would pull away. This closeness, this penetrating and dissecting gaze conform with 20th-century thought and the rules of the media. Scientific research is being carried out into ever-more minute parts; it is no longer whole flowers that are carefully dissected and analysed but matter itself is broken down into microscopic particles in the interests of acquiring previously hidden knowledge. This super-closeness is reflected in the close-up focus of paparazzi photography and pornography which enables the media to display the private and intimate within a public context.

Since the 1970s, this approach in art has been accompanied by another point of view which, in terms of form, would appear to turn the clock back. In portraits taken of and by themselves, for example, by Urs Lüthi and Cindy Sherman, or in Richard Avedon’s portraits of the rural population in the American mid-West, or Robert Mapplethorpe’s portraits of figures from New York artistic society, the theatrical staging reappeared. In each case there was a consensus that this was photographic theatre and therefore a certain amount of choreography was necessary. The change as regards form is astonishing, for, in different ways, the pictures once again create stages on which the figures enter, introduce themselves, and take up a pose. The preconditions for this change were a different understanding of the human being and a different approach to truth. The ego as the tough kernel to be cracked by power and cunning so as to discover the absolute truth of the human being lost its attraction and forfeited its absoluteness. It split, was crushed and pounded as if in a mortar, splintered in the prism of analysis to re-emerge as many egos: wished for, unwished for, achieved, willed, ordered, experienced, and playful. The truth does not lie in a single one, it is in them all, in the constellation, the arrangement of the parts. It is not absolute and eternal, it is temporally limited, valid only for a time. Then let’s play it. Let’s play existence, let’s try different realities. Perform, present, says the new text on the wall; the attributed, ordered identities, just as much as the wished-for, struggled-for, longed-for ones. For ourselves and for the others. “Lüthi weeps for you too” is the title of an early work by the Swiss artist Urs Lüthi from 1970, in which he offers himself as a living surrogate, a stand-in, made-up, dressed in a snakeskin jacket, with tears on his cheeks, in the world of mediatised emotions. Identity takes the place of truth. The absolute of the ego is superseded by the construction of the identity. This change needed a new kind of photography—one that formally resembles the theatrical photography of the 19th century but that makes its appearance under different circumstances. The theatre is no longer the instrument of the affirmation ritual, the reinforcement of the figure in its appropriate representation; it no longer serves the glorification but the disintegration, the liquefaction, the analysis of the figure. Andy Warhol was a master at mixing all these elements. He created icons and destroyed them at the same time, through duplication, causing them to burst in the air like small balloons.

It is from this context, consciously or unconsciously, that the work of Rineke Dijkstra emerges. She herself says that she was directly influenced by Irving Penn, Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus. This is important in as much as Rineke Dijkstra twists and changes almost everything. She is not shrill like Diane Arbus could be, she is not voyeuristic like Richard Avedon sometimes was, she is by no means playfully ironic like Urs Lüthi. She does not seem to want to be coolly, operatively conceptual like Thomas Ruff, nor produce neo-classicism enriched with art-deco elegance like Robert Mapplethorpe. So much for what her work is not. But what is it then, what effect does it have, what is its purpose? Here I would exercise caution in making any pronouncement. In her various series, Rineke Dijkstra gives us a new interpretation of the portrayal of the human being in the classical sense, her portraits seek a classical expression in the present in terms of both form and content. The word classical as I am using it here means primarily a composed, purified portrait that nevertheless makes a profound and multi-layered impact, and it also refers to the idea of classicism itself. Let us take a closer look.

Rineke Dijkstra “constructs” stages for her photographs through the choice of site and scene—her own and that of her subject. She structures and marks them out through her framing, whether outdoors in the middle of nature or indoors against a wall. The landscape acts as staffage, aiding the construction of the picture and the integration of the figure. In the series on bathers, taken between 1992 and 1996, the staffage consists of sand, water and sky. The figures emerge before and against the backdrop of this threefold band of stripes. Each takes up their pose, sometimes embedded in a dark, cloudy background, sometimes freely, floating delicately because the light, flat sky threatens to dissolve and excise the figure. The weather, and with it the mood of the picture, changes as if the background had been altered. In the series on the soldiers on the Golan Heights from 1999/2000, the bushy, undulating landscape rolls towards and away from the figures. The figures emerge from and are rooted in the landscape. Landscape and sky divide the background up into two parts of almost equal size, with the figures inserted in the middle as if their and the picture's centre were one. Standing firm and still, they occupy and fill the centre. In both groups of work, the landscape is so strongly reduced that its effect is basically no different than, for example, that of the bare wall in the indoor portrait of the mother after the birth of her child (1994). The setting on all these “stages” is so reduced, so purified, that there is hardly anything to compete with the figure. When other objects play a part, they refer to the figure, conform to its actions, its natural surroundings. This is where Rineke Dijkstra’s photographs differ from the representative 19th-century portrait which contains attributes that are alien to the subject and belong to the studio, attributes that suggest a general bourgeois ambience independent of the person being photographed.

Rineke Dijkstra’s figures are simply “there”. Whether full- or half-length, frontal or in three-quarter view, whether indoors or outdoors, the figures stand their ground, self-evident, calm, simple, almost everyday. There are no histrionics or wild contortions, no dramatic gestures or expressions—the pictures reject all expressiveness, the figures radiate a basic sober calm in spite of all their individual differences. There they stand, facing or slightly turned away from, but always focused on, the camera; their arms hanging down, their eyes directed, boldly or shyly, towards the camera and towards us as viewers. This simplicity of attitude reinforces the simplicity of the visual composition. But if we compare the portraits taken in the open air with those taken in closed-in rooms, the outdoor figures resemble free-standing sculptures, modelled, “carved out” by direct and indirect natural and added artificial light, while the indoor figures make a flatter, more monochrome and abstract impression, rather like inset wall reliefs. The former emerge out of the landscape, the latter are immersed in the background. This changes the impact of the picture. The open-air pictures make a slightly more accentuated, denser impression, they are somehow fuller than the indoor images. They all, however, have one thing in common: a portrait could hardly be more simple; not only the landscape, not only the interior scene, but also the figures are purified and abstracted, almost entirely free of any embellishment.

It is first of all this formal treatment of the subject and the background that make a “classical” impression in these photographs. The reduction is further reinforced by the choice of the figures. All the people Rineke Dijkstra photographs are young although, with a few exceptions, e.g. the Berlin zoo pictures which, with portraits of children, seem to allude to the German fairy-tale, most of them are no longer children. They are adolescents and young adults—young mothers, young soldiers, young toreros. They are at an age in which character traits are gradually beginning to form, in which there are already suggestions of distinctive attributes, but in which the features still make a very bland impression, almost like polished marble. Signs of time and of a personal history are barely visible. Thus here, too, there is no baroque opulence, no relentless asceticism or gnarled authenticity, but—compared with the wide field of expressive possibilities of which human beings are capable—they are rather “characterless”, abstract, laundered figures. More than any aspect of the actual content of the photograph, this has a additionally soothing effect on the picture, a calming of the visual impression. We see most of the young men and young women as they frequently appear in sculptures—even purer, even more ideal .

All this means that we, the viewers, must gain an insight into the visual world of Rineke Dijkstra; that, used as we are to the extremes of our frequently, insipid, colourless and stressful everyday world and the shrill, brash, colourful media world, we must once again learn to look at calm, apparently simple pictures that are nevertheless endowed with a high level of presence, to be aware of tiny yet highly meaningful changes, and to recognise and absorb a reduced and conspicuously subtle and at the same time rich colourfulness. Rineke Dijkstra herself never says that she has been influenced by painting, and yet her work is often eminently painterly as regards her way of handling colour: the way in which she places her colours, their relationship to one another, the way in which one colour is taken up by another or contrasted by a third. And, despite the element of coincidence that always plays a role in portrait photographs, it is not the photographer’s intention to produce pictures that are from the beginning posed, clothed, arranged and illuminated. The level of coincidence is controlled at a later stage through rigorous selection and cropping.

In this minimalistic field of vision, in this selection, “it” occurs, it happens, it becomes a picture, a visual presence and a time-related past. Rineke Dijkstra works pictorially, she looks for the picture potential in the portrait. In the photographs of people bathing, we can compare the shy adolescent gestures of a girl from Eastern Europe with the cramped imitation of assumed poses, observe the contrast between a boy’s oiled body, as brash as it is awkward, and the fairy-like appearance of a blond girl in a long green dress; we can study the hands of the young people, clenched into fists or resting on the thighs of lanky boys with conspicuously long arms that hang behind their backs and reappear between their legs; or can we wonder how it is that even the sea looks richer or poorer according to where the picture was taken. This series plays lavishly with the young people’s surroundings, clothing, natural, inborn differences and codes of conduct, and shows how attitudes, gestures, expressions and clothes form themselves into symbols, into meaning, only to disintegrate once more because these young people are in a stage of transition in which the child has not yet been cast off and the adult not yet integrated. In the picture series “Almerisa” and “Olivier”, Rineke Dijkstra gave her observations the additional dimension of a chronological context. Since 1994, she has photographed Almerisa, a child asylum seeker, at irregular intervals. Similar to a long-term body study, we see how—in addition all the other changes of clothing and expression—the legs and feet of the child sitting on a chair gradually grow nearer to the floor until they are touching it. As soon as she is able to rest her feet on the ground, the whole attitude of her body alters. The sweet, shy, awkward girl sitting on a chair suddenly changes into a young, self-aware teenager looking boldly into the camera. The series on Olivier, the foreign legionnaire, from his voluntary recruitment through the various stages of his military career, gradually reveals an almost imperceptible cooling of the expression in his eyes accompanied by a sharpening of his facial features, according to the stage in his training, according to the clothing he is wearing. Fine feathers make fine birds; the uniform makes the man.

The series on the young mothers, the toreros and the Israeli soldiers on the Golan Heights have a decisive common factor: they are all portraits taken after an important event, a difficult action: only shortly after the birth of their children the mothers stand naked with their babies in front of a bare wall in their homes; the young toreros were photographed shortly after the bullfight, with blood on their faces and shirts and torn jackets—to be washed off and cast off; and the young Israeli soldiers pose for their portraits immediately after their first bout of shooting practice on the Golan Heights. In all three series the young people are photographed in the reverberation of a special, powerful occurrence in which they took part, for which they were responsible, to which they subjected themselves: giving birth to a child, ritually fighting a bull (and in this case really acting in a play because the torero appears as the female element, in female clothes, fighting the male bull), and shooting with a machine gun, completing their first military shooting training. The portraits reflect the events in their faces, their eyes, their auras and the energy in their features. Their clothes symbolise the extent of their self-exposure: naked, in theatrical costume, in combat uniform.

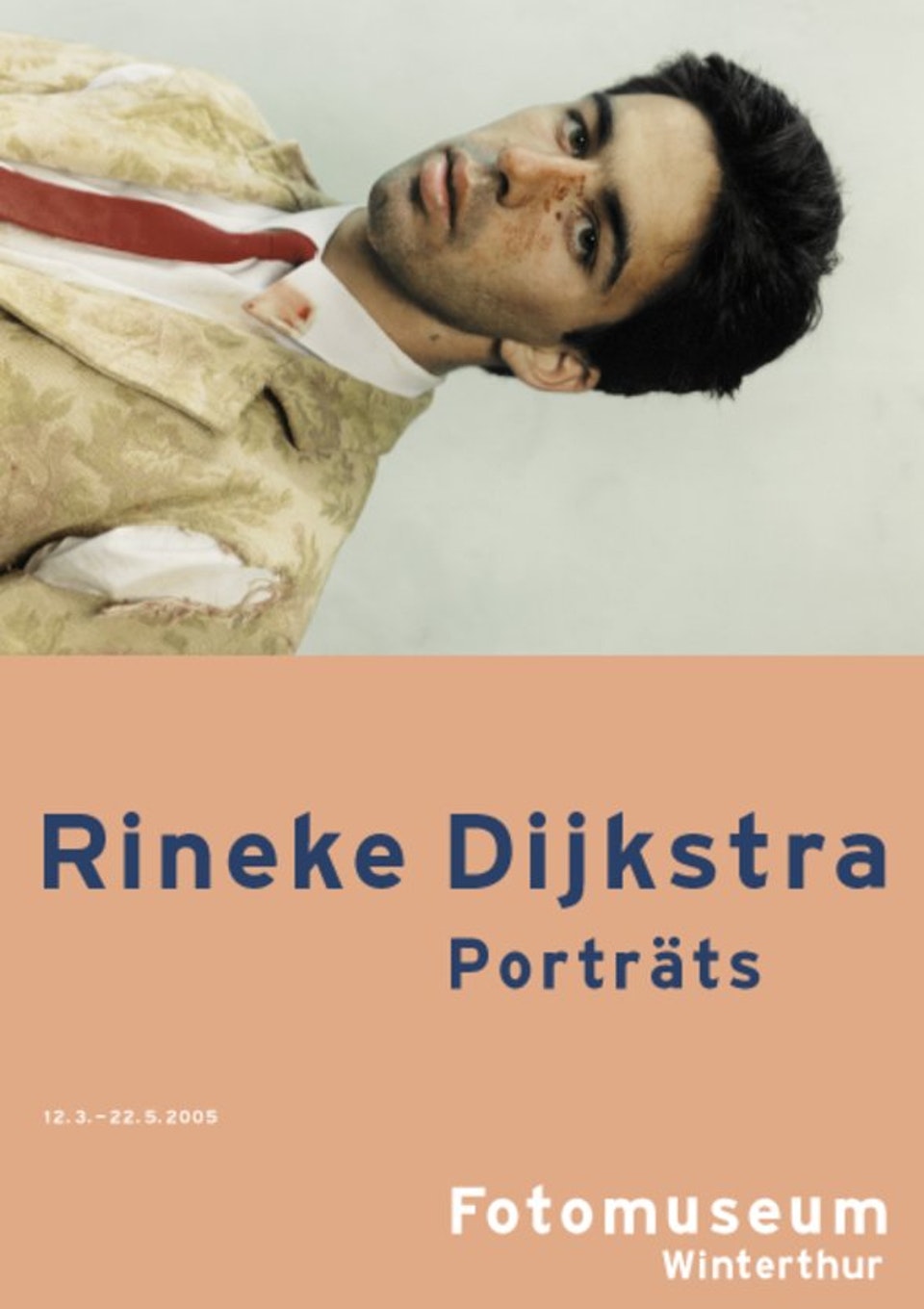

The two closely cropped photographic busts of “Tia”, the first taken shortly after the birth of her child and the other five months later, show subtle yet impressive changes in her facial expression, a yardstick of the strength and energy that Tia gained in just half a year. The impression of exhaustion, of inner emaciation in the first picture gives way to that of a revitalised, restrained yet radiant woman in the second. The changes are minimal, reproducible in a poetic rather than a descriptive language, and yet there is a world of difference between these two pictures. In terms of form and content, they lead naturally to the portraits of the toreros, also taken as busts against a light blue-grey background. The young men bear the traces of the struggle, the dance, the fight; like Tia, they reveal a certain degree of fatigue and exhaustion; their ties have slipped, their faces are tired, their eyes slightly veiled. Their expressions—pale and exhausted or bold and impudent—vary from picture to picture, from torero to torero. The impression seeps through the skin to the surface of the photograph as if through a semi-permeable membrane in an osmotic process. In some ways—in the three-quarter-length format, the soft modelling of the colours and the emotions hidden in the faces—these photographs are reminiscent of old master paintings. Except that a classical painting would never consist of a portrait painted after the climax, after the deed. Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits have to do with experience, not will.

The Israeli soldiers photographed after their first shooting practice make a more balanced impression. After all, it was only practice, not a real battle. Their faces are accordingly more relaxed, more bemused; their poses are bolder, they present themselves to the camera in full battle dress with their machine guns and camouflage; one of them still slightly uncertain, a second already more at ease, a third in the pose of a proud soldier. The young faces contrast with the machinery they are carrying, with the power of the weapon in their hands. Generally speaking, these pictures make a more photographic and colourful impression than those of the toreros. They are photographed in the open air in bright side lighting that casts strong shadows.

In 1766, the German poet and thinker Gotthold Ephraim Lessing wrote a book entitled Laokoon oder über die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie. Mit beiläufigen Erläuterungen verschiedener Punkte der alten Kunstgeschichte (Laocoon. An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, Johns Hopkins University Press) in which he compares art and poetry. In it Lessing takes as a model for reflection the deadly struggle of Laocoon and his sons, a marble sculpture from the second half of the 1st century B.C. (the original in bronze has not been preserved) by the sculptors Hagesandros, Polydoros and Athanadoros from Rhodes. The sculpture shows Laocoon and his sons struggling in the coils of huge serpents. Lessing interprets it as an example of the importance of portraying not the climax, the extreme moment of the fight, but the moment before, because it is only in the peripetia, in the sudden change in events and emotions, that the observer can experience catharsis:

The master worked at the highest level of beauty under the assumed circumstances of physical pain. The latter, in all its disfiguring intensity, was not compatible with the former. Thus he was obliged to minimise it; he had to reduce the bellows to groans, not because the bellows betrayed a base soul, but because they distorted the face in an abhorrent fashion. In our mind’s eye, Laocoon only has to open his mouth wide, and we judge. We let him bellow, and we see. It was a composition instilled with a sense of pity, because it revealed beauty and pain at the same time. Now it has become an ugly, repulsive composition from which we gladly turn away because the sight of pain arouses disgust, without the beauty of the suffering object having the power to transform this disgust into the sweet sensation of pity.

It is remarkable how Rineke Dijkstra, whose work has an affinity with the classical portrait (harmony, completeness, unity) chooses to portray not the moment before, the leading up to the climax, not the climax of the struggle, the fight, the event, but the moment after, the relaxation, the exhaustion after the will is spent; the “human being as will, as intention” has for an instant forfeited its power to act and, although triumphant, is wounded and scarred and succumbs to relaxation. She seeks this soft, almost flat situation. The persons portrayed open up, allow themselves to be themselves, cease to strike a pose in the fight against the almost automatic and inevitable fact of having their picture taken. Here, the subjects of the portraits—like Rineke Dijkstra’s role model Diane Arbus—reveal more than they would wish to, show themselves in a different, perhaps disadvantageous light. They lose control over “their” pictures, the poses soften and the general state of being human, of existing in the broadest sense, shines through.

In her choice of the “post climax” as the starting point of three focal groups of work, Rineke Dijkstra opens up a field of subtle, “weak-willed”, submissive insights into the human condition. She shows the first scarring, the first achievement, the first “post-experience” of young people, and she shows it as the first sign of maturity and depth. She creates portraits that are not a confirmatory ritual but which represent a balance between the individual, the group (the bathers, the mothers, the soldiers) and universal human existence in general in the face of birth and death, thereby developing a new and very individual interpretation of the classical portrait. In the age of brash poses and shrill screams, Rineke Dijkstra’s calm, full presence creates a new form of monumentality and a new form of beauty in the photographic portrait.