There is something comforting and reassuring about nouns. They name things. Things that are named can be ordered according to familiar patterns and categories. Once they have been safely pigeonholed, they can be set aside and we can breathe a sigh of relief as we pat one another knowingly on the shoulder. Sometimes nouns have an abstract quality that creates a sense of detachment: the Third World, death, catastrophe – so far removed and so intangible that they hardly affect. After all, there are rescue teams taking care of things there. We may talk about such things, and even argue about them eloquently, but it would be uncool – and so last century – to actually show emotional involvement. Involvement can be delegated. Verbs, on the other hand, are more direct and open. They are like bulls in an open field, blundering around in unpredictable directions, impossible to simply push aside, snorting and pawing at the earth, leaving traces, making us feel uneasy. We treat them with caution, but we cannot pin them down. We can jump on and go along for the ride, or we can fall off and be crushed by them.

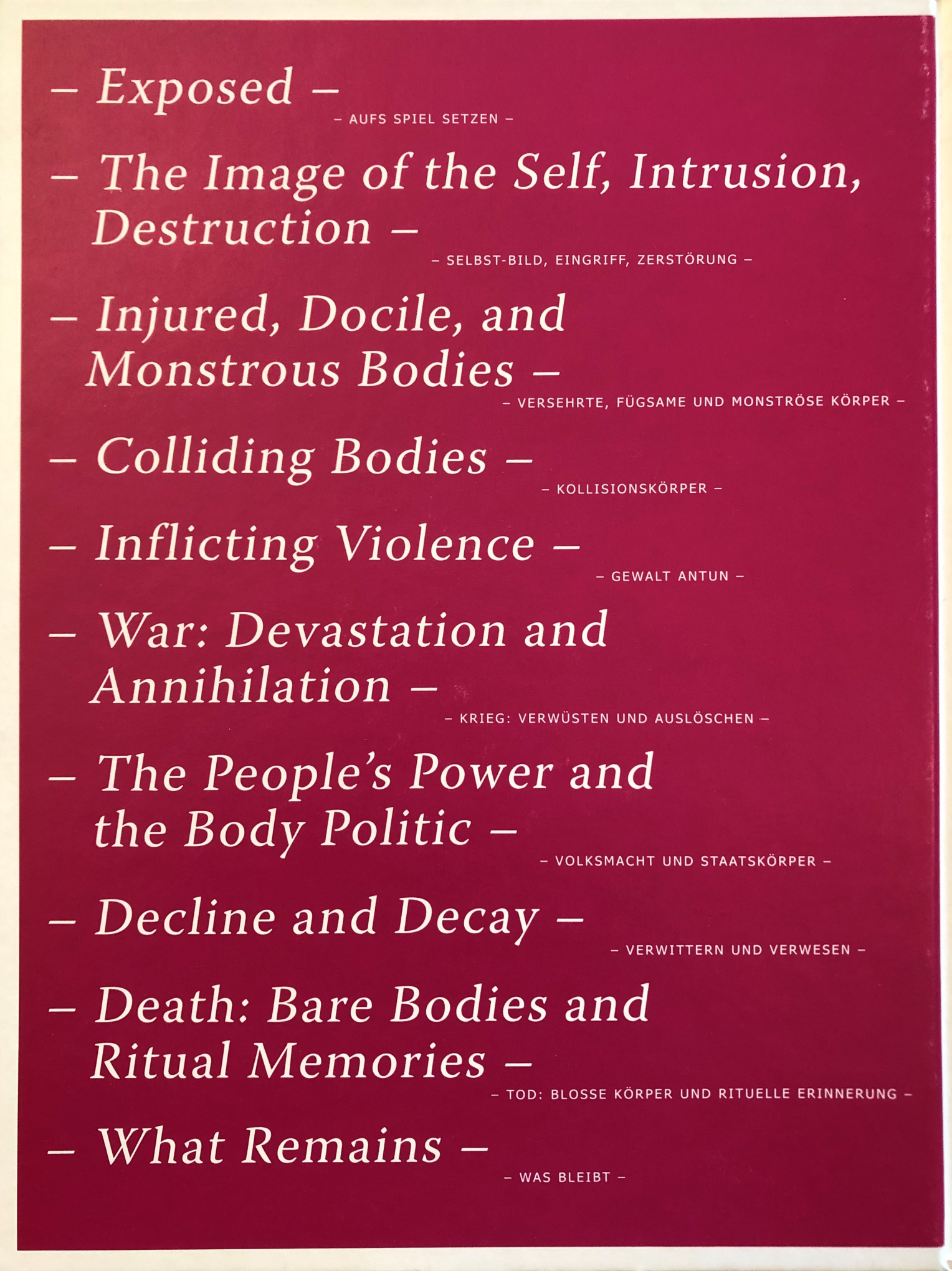

This book begins with images of energy and movement: taking a gamble, venturing forth, getting involved, going with the flow, not knowing where the current is heading, how the game will play out or how the struggle will end. Submitting to danger, drifting with the crowd, yet still being able to draw the line between the “self” and the “others”; indulging in games with no clear outcome, in fights with rules, in sex involving power-games. But always, and most importantly, voluntarily. These initial images follow on from Darkside I – Photographic Desire and Sexuality Photographed. The situations and energies they describe are similar. They are about physical risks, about pushing the body to its limits, daring to compete, and about risk-seeking in pursuit of pleasure and bonding. Diving into water, entering the ring, risking injury: ambivalent, but driven by positive energies, by strength, ambition or eroticism, with no fear of the consequences nor any wish to know what they might be.

So far, the body is generally unscathed and at one with itself, in spite of the risks taken; radiant even after a fight, smiling in spite of any physical or mental injury. But from here on in, the boundaries shift. Free Fighting is gaining ground in the ring and in everyday life. The body as the constant refuge of the self, of a being subjected, for the most part, only to natural fluctuations and developments, is redefined, reconfigured, inscribed and pumped and injected. The body is trimmed, adjusted, adapted to new imagery. Its integrity is violated. Reshaped and interfused by the images of many different cultural bodies and by new, sometimes contradictory, identities, it is transformed from a dwelling-place into an instrument that is constantly being sharpened and polished, trained and toned. Through radical physical asceticism (“Thirty-Two Kilos” is the title of Ivonne Thein’s series of photographs), hormonal and surgical interventions, the body is adapted to comply with the latest requirements and to project a self-image fashioned by changing cultural perceptions, labels and brands. Shifting identities generate shifting bodies. The line between enhancement and mutilation, between adaptation and destruction is a very fine one; the boundary to derangement and self-effacement is easily crossed. Changing cultural perceptions are taken as justifying major interventions, confusing all sense of identity and body-image to the point of self-destruction. And even to the point of suicide: by rat poison (Andres Serrano) or by leaping from a window (Furuya’s epic series about the decline of his wife Christina). Free will gives way to various compulsions.

Sophie Ristelhueber’s work addresses the theme of the injured body: “Injured, Docile, and Monstrous Bodies”. Bodies that are distorted and crooked, bodies that are maimed and poisoned, rotting away from within. Bodies ravaged by viruses or cancer, by information systems that attack the body from within, destroying its immune system, turning it against itself, devouring it. Ristelhueber’s photograph of a woman with a massive scar running all the way down her back tells of a body that has had to be cut apart and opened up, treated and then sewn together again with multiple stitches. The huge scar will long bear witness to this act of disclosure, of revealing what lies within. Scars mark and shape the earth, the mountains, people, bodies and even souls (a theme addressed in Sophie Ristelhueber’s work), reminding us of the fragility of the body and its temporary or permanent disfigurations. While severe injuries are often the result of some natural disaster, in the case of W. Eugene Smith’s photograph of blind, disabled Tomoko Uemura, they are not. The young girl’s physical deformity is a legacy of the grossly negligent, indeed murderous, pollution of the environment with mercury near the Japanese city of Minamata in the 1950s. When intervention is necessary, we temporarily delegate the body to a machine, handing it over, losing control of it (as in the video by Aya Ben Ron). For the duration of the intervention, the body becomes part of an external, substitute system to which it forfeits its sovereignty almost submissively. Psychological or mental illnesses seem to mark the body from within, changing it from the inside out. The body seems to give in gradually to the misdirected inner energies and impulses. As in the photographs by Hugh Welch Diamond and Jerome Liebling, the figures appear to be shaped by their inner state. According to our eyes and our sense of aesthetics, nature produces both bodies of immaculate beauty and monstrous bodies that are aberrations of creation. The monstrous dwells within us; it is a part of the fragile balance in nature and culture, and yet we tend to relegate it to the fringes of the city, to the test-tube, to the clinic. We sweep it out of sight – and succumb to the illusion that it will never approach us again.

Bodies collide, crash, burn, explode; bodies are shot at, injured, ripped apart, mutilated, hacked to pieces; bodies can be executed, hanged, decapitated, poisoned, electrocuted. Blood is spilt, corpses are buried, swept away, burned. The energy vector has changed direction. The body no longer steps out into the world with easy abandon, marrying, staking out its territory. Instead, it is buffeted by a massive thrust-reversal of energies. Physical, mental and emotional forces attack its integrity, injuring it, destroying its spiritual and material system. The sections on “Colliding Bodies”, “Inflicting Violence”, “War: Devastation and Annihilation”, “The People’s Power and the Body Politic” show images of domestic violence, of assassination attempts, wartime attacks, bomb explosions, mass murder, xenophobic rage, structural and social violence, and state power.

Violence, it would seem, needs images. Violence seems to feed our visual imagination. In her work “La lame de rasoir”, Sophie Calle reflects on the imaging of violence, on the tension between the visible violence of the image and the hidden violence of reality: “i posed nude every day for a drawing class, from 9 a.m. to 12 noon. and each day, a man who was always seated in the first row, on my far left, drew me for three hours. at noon he would take a razor blade out of his pocket and compulsively slash the drawing he had made. i would watch. then he would leave the room. the drawing would remain on the table as evidence. this was repeated every day for twelve days. on the thirteenth day, i didn’t go to work.”

Just what was being castrated by the slash of the razor blade – the drawing, the ability to draw, sexual fantasies – remains unclear, as do the implications of what the photographed drawing shows. It harbours the potential for monkish self-castigation and murderous intent.

Gradually, the body goes into decline. It ages, shrinks, stiffens, withers, disintegrates and decomposes (in the works of Daniel Schumann, Elisa González Miralles, Sally Mann etc.). It loses its energy, suppleness and life-force; its systems fail, and rogue prion folds effect behavioural and personality changes. Self-images crust over, social body-images are diluted, the quest for identity loses momentum and importance. And what remains? The assertion of dignity against the decline of the body, then death, then just the body itself, the funerary rites, the rituals of remembrance, the anatomical knowledge of the body (in the works of Adam Fuss, Michael Ackerman, Hans Danuser etc.). Verbs fall silent. Death, unlike life, is a barely tangible, abstract concept, a concept that is negatively defined: drained of energy, devoid of life or spirit. A strange, existential nothingness. We are left with reflections on life and death, on conflict and reconciliation. We are left with an insight into what is necessary. Some of the authors in this publication address the affinity between photography and death.

Violence attracts images. The visual world of western culture is full of images of violence – both random outbursts of violence and military violence, regulative state violence. In a strange reversal, societies have shut away images of life-affirming, life-giving sexuality, banishing them to the fringes of obscurity, whereas images of dark and excessive violence have been brought into the light. The reasons for this are many and complex. They function in much the way as nouns do, by naming something: the tangibility of the portrayal comforts us, as a means of grasping the horror. Images of violence excite and electrify all those of us whom the horrors have passed by. They read like memorials, like visual tablets of the law, when they portray state and judicially sanctioned violence. They claim to be enlightening, accusatory manifestos and moral appeals for an end to horror in general but, above all, for an end to the specific horror portrayed in the image. And they sell. They boost media circulation. Images of horror, terror, murder and branding, shocking photographs: they fascinate, for the reasons already mentioned, but also because of a desire to look at the dark side of civilised, orderly life. Having a part in something without actually participating – a kind of voyeurism of violence and its portrayals.

Nowhere is this phenomenon more compellingly evident than in the photographs of lynch mobs and their predominantly black victims in early twentieth century America: it is further underscored, not only by the sheer numbers of onlookers who willingly posed for the camera, smiling and laughing, after the crime, but also by the disturbing fact that such photographs were actually reproduced and sent as postcards with friendly greetings. Postcards showing the horrors of the first world war, with dramatic depictions of the bodies of dead soldiers from the Franco-German front, Mexican crowds gathering to feast their eyes on the scene of an accident or a crime, and subsequently on the press photos by Enrique Metinides, all show that the voyeurism of violence knows no geographical, temporal or cultural bounds. The cathartic, purifying effect that portrayals of pain and violence have sought to achieve since the age of Greek Tragedy, cannot be found in these photographs.

Images themselves attract violence. Images generate energy, power and violence. They not only represent, but they also present; they are monstrative. “Each image is a monstrance … the image is of the order of the monster,” writes Jean-Luc Nancy in “Image and Violence”. “The monstrum is a prodigious sign,” he goes on, “which warns … of a divine threat. The image is the wondrous force-sign of an improbable presence irrupting from the heart of a restlessness on which nothing can be built. It is the force-sign of the unity without which there would be neither thing, nor presence, nor subject. But the unity of the thing, the presence and the subject is itself violent. It is violent by virtue (that is, by force) of an array of reasons.” The image must be able to present itself. It must be able to “tear itself from the dispersed multiplicity, resisting and reducing that multiplicity”, according to Nancy. The image must “externalise itself, while also excluding from itself that which it is not and ought not to be, that of which it is the refusal and the violent reduction.”

To this visual power can be added photography’s power of the factual, the power of realistic portrayal, and the framing of time and place by which the camera, the choice of shutter speed and lens, can separate the image from the continuum of reality. What is included in the picture and what is left out of it, what is shown in close up or in the distance, sharply or out of focus, are all decided absolutely. This power to transform every factual “that-has-been” into a specific, causative “that is how I (the photographer) saw it” is an inherent trait of the photographic medium. We can also discern a kind of performative power: the act of photographing not only documents, but also intervenes in, what is happening. Children laughing, women crying – because they are being photographed. Certain acts of war occur only because a camera is present. Thomas Macho begins his essay in the present publication with a famous example from the history of photography:

“Images cannot document the context in which they were created – as evidenced by the famous photograph taken by Robert Capa on 5 September 1936 during the Spanish Civil War. The much-commented synchronisation of the shutter release coinciding exactly with the impact of the bullet that killed the 24-year-old militiaman Federico Borrell Garcia was not a matter of pure chance; the skirmish had been staged for the camera.”

Once the photograph exists, further questions follow. In their essay „Hinter den Kulissen der Gewalt“, Daniel Tyradellis and Burckhardt Wolf analyse a photograph by Jeffrey Silverthorne from the field of forensic medicine and ask what the violence of the photographic moment entails. They quickly come up with eight salient points: 1) the real violence itself that the photograph actually documents; 2) The violence meted out by the police officers in the name of authority, setting in motion a mechanism that subjects the perpetrator to legally sanctioned violence; 3) The violent act, or sacrilege, committed by the photographer in taking a picture of a lifeless person in such a situation; 4) The journalistic or artistic “act of violence” in publishing the image and presenting what may be the most intimate of all images – that of a dead body; 5) The violence of the unfiltered viewpoint chosen in taking the photograph and in radically affecting the way we look at it; 6) The violence or strange insistence with which the photograph has subsequently been manipulated; 7) The relentlessness with which the publishers of this photograph have chosen it as a cover picture, presenting it to their readers whether they want it or not; 8) The violence or stubbornness of the spectators in reading into the picture whatever they may choose. And finally (for the moment), another point should be added: the incredible power that photography, especially published photography, wields over our memory. Only that which has been photographed still exists later in the individual and collective memory and carries any weight. What we know only through hearsay is bound to lose out against it.

Plato, as cited by Abigail Solomon-Godeau, maintained that “ ... it is not by means of the image that moral, ethical, or political knowledge is produced”. Some 2,400 years later, we are living in a visually sophisticated media world in which the latest, the closest, the most horrific, have become redundant. As Trotta, a figure in Ingeborg Bachmann’s short story Three Paths to the Lake, complains to his photographer girlfriend, “Do you suppose you have to photograph those devastated villages and corpses so that I can imagine what war is like, or take pictures of children in India so that I know what hunger is? What kind of stupid presumption is that?” Who photographs, who publishes, at whose request, for what audience, and with what intent? How much money is involved and how good is the quality of the print? All these questions come into play time and again in the images of horror and of physical, human terror. For the image rarely stands on its own merits. There is always an overall context that makes such images seem relevant, irrelevant, or simply shocking. And yet, reality is always more violent than any image.