Zoe Leonard takes photographs and shows us photographs. For twenty years her photographs were almost invariably black and white, printed on fiber paper. More recently, especially with the major Analogue cycle that she worked on for nearly a decade (1998–2007) before it was shown this year at documenta 12, colour photographs have become just as much a part of her work. These are analogue color photographs, generally taken with an old Rolleiflex camera and printed on classic color photographic paper, as C-type prints, or occasionally as dye-transfer prints. The formats themselves are not particularly unusual. The smallest are about 10 x12.5 cm (4 x 5 in), while the largest are no more than 100 x 120 cm (40 x 50 in). What is remarkable, however, is that during the Eighties and Nineties, Zoe Leonard decided not to go along with the all-pervasive tendency to blow up small negatives into billboardsized photographs.

To make such introductory remarks in an essay about Zoe Leonard’s predominantly photographic oeuvre which spans some 25 years may come across as banal, or simply stating the obvious. Yet these words tally precisely with what seems to underpin every one of Zoe Leonard’s photographs so emphatically: “I see, I photograph.” “I am showing you what I have seen and photographed, and not what I have invented.” “This is how it is.” Whenever we look at her photographs, these are the subtexts we read. Right across the board, in all the subjects she has approached so far, we find ourselves looking at a matt or semi-matt fiber print that seems to speak first about itself and then about photography in general. The black edge of the negative, which is always included in the print, surrounds what is seen, framing it and defining it both as a fragment of reality and as the totality of what has been photographed, seen there and shown here. Various imperfections—a scratch on the negative, specks of dust in the enlarger—which might occur during the process of developing and enlarging the photographs, are not edited out, as they would usually be, but are deliberately left as they are. Printed on different types of black-and-white photographic paper, these imperfections actually emphasize and address the overall process of photographing, developing and enlarging. The physical carrier of the visual information does not disappear as it does, say, behind a dazzling advertising photograph, where its presence is lost under the glossy perfection of the printed image. It is shown clearly and thus becomes a tangible and perceptible part of the image. Just as we hear the crackling of the radio at the end of a broadcast or see the flickering of a video, so in Zoe Leonard’s photographs we can always discern the materiality of the image and the photographic process behind the visual information.

The strong presence of the carrier, of the material itself, tempers the sheen of the surface reflection, so that the image emerges from the material of the photograph. Pictures of maps and models of cities, aerial views of waterways and settlements, photographs of fashion shows and museum displays—all manner of motifs and themes peel out of the background like graphic signs, some pale with bursts of light, some dark with areas that abruptly break off from paleness to a deep, sooty black. Zoe Leonard takes photographs, but she approaches the photographic image as if it were the site of an archaeological dig, uncovering traces and remains with varying degrees of precision and to different depths. She takes photographs, but her prints are redolent of charcoal drawings, or of long-buried visual treasures. It is as though she kneads and molds her photographs until fabric and image, light and shadow, motif and theme all amalgamate into a single compound that originates in the depths of her creative being, and yet what results look almost like found photos. The creative process appears to be shaped and accompanied by a kind of formally-aware anti-formalism, a materially-aware anti-brilliance, an image-aware non-standard photography—all in the full knowledge that it takes both components of each of these dual aspects to describe her endeavors. In an attempt to categorize her approach, we might venture to describe her work as Fotografia Povera, as a kind of Arte Povera of photography. Or, avoiding comparisons in the history of photography, it might be described as a cross between a Beuysian approach to materials and Minimal art, in which the visual content is tapped from within the material itself, rendered visible in the process, and then brought to life through light.

In a way that is rarely found in contemporary photography—given that the industry, with its materials, films, papers and developing fluids, already predetermines certain standard paths—Zoe Leonard ploughs her own idiosyncratic furrow in her visual approach to the world, without ever appearing pretentious or historical. She then spans this ground with a celestial dome, starred with questions and references about the conditions and limitations of seeing. Just as she addresses photography and its materiality in every one of her works, so, too, she addresses the idea of seeing. The two portraits at the beginning of this book can be taken as a leitmotif in this regard. In both pictures, we are sitting in the car; we are traveling with the camera. In the first picture, we are looking at the back of an elderly woman’s head, at her disheveled hair, and watching her as she gazes through the windshield, without being able to see what she sees. The picture is framed several times: by the edge of the negative, by the surround of the windshield and by the rearview mirror—each frame in turn delineating a different field of view. The second picture also shows a woman, this time in the back seat of a car. We look into her face. She has her eyes closed, introspectively, taking no notice of the landscape rushing past. Two other distinctive features inform this image: the strong sunlight that falls through the rear window, bathing the back of her head in light, and the few strands of hair that fall into her face, as though swept forward by the force of the light. These signs form a counterpoint to our experience of photography and the world; they interrupt the flow of perception and seem to underpin this introspective gaze, to emphasize this sense of detachment. The biographical aspect of the two photos—the first figure is the artist’s grandmother; the second her mother—gives the theme of seeing an added significance, pinning it down as an existential part of her life and a central theme of her art.

In many of her earlier photographs, Leonard lifts off, quite literally, from the ground, getting into aircrafts or helicopters and photographing the world from above: Niagara Falls, rivers, railway tracks, the roofs of buildings, green zones, and then, in close-up, city models, street plans and maps. The unusually steep downward view from such a high vantage point is reminiscent of reconnaissance flights, or hot-air-balloon rides in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; of military surveillance flights over enemy territory, or ordinance survey photography, used as the basis for maps and plans. The atmosphere in the pictures alternates between a sense of wonder at the sight of such breathtaking beauty, and a gloomy bewilderment at seeing images so close to night-time military reconnaissance photographs. Irrespective of their subject matter, the photographs are representations of seeing, perceiving, discovering, surveying; they pose questions about how we see, from what viewpoint, and about how the way we see affects our attitudes. The frame of the negative, included in the print, puts its own stamp on the topic. Just as we underline a word when we write to emphasize its significance, so Zoe Leonard underlines the fact that her work is always about seeing, always about questions of how much we can understand, or grasp at all, when we look at the world. And she does this in a simple and casually incisive way.

Her images of clouds and cloud formations—towering, gathering, fluffy cumulus clouds—are seen and photographed through the windows of an airplane. They address the idea of framing in two ways: by showing the edge of the negative and by showing the outline of the windows, which act like distorted camera lenses or double-walled screens, allowing us to glimpse the fluidity of the sky, where clouds gather and disperse; a world of brief configurations, on the boundary of the figurative and the abstract, between accumulation and disintegration. Photographing these clouds from an aircraft in flight as they scud along breaks down the traditional standpoint, and with it the status of knowledge; it sets our way of seeing in motion. A visual (Einsteinian) relativity seems to creep into these pictures.

Surprisingly, the steep view from above in Zoe Leonard’s aerial photographs has little affinity with Russian Constructivism, or with the Neues Sehen (New Vision) propagated by the Bauhaus in Germany, nor indeed with any other era of photography or film. Her views are devoid of the heroic gesture, the shock of the new, or the formal considerations that informed these movements. Instead, her photographs recall the broad field of non-artistic, utilitarian photography. Like found photos, they are relics of some unknown action, a visual record taken at some other time for some other reason. Only the cloud photographs remind us, probably unwittingly, of Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents of the Twenties and early Thirties: increasingly abstract cloud pictures which he felt equated to emotions and inner truths.

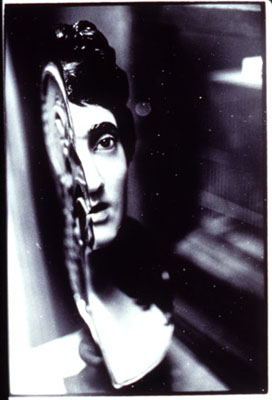

Just as Zoe Leonard approaches the idea of seeing by looking at the world from above, in her photographs taken in many museums and galleries she addresses how we are conditioned by the way we see things in the world around us. Take, for instance, the view into a display case, where two empty bearskins hang side by side; or where a female anatomical model is posed, the draped fabric of her plinth and her defensive gesture appearing to indicate chastity. Or take her view of a bullring—an overall view from high up, looking down into the arena, where the bull and the torero are reduced to tiny figures—which clearly demonstrates the power of order (and the order of power) in the ceremonial arrangement of the architecture, the onlookers, and the ring itself. She shows us a bearded woman, from five different angles, preserved and presented behind glass. There are showcases of recumbent wax models, including, for example, the model of a woman, her upper body exposed, adorned with a necklace, her hair flowing. And there is the encounter between two little girls and some stuffed apes in a natural history museum, where the models of pre-human creatures are exhibited next to a diagram of the evolution of man. The children are looking at our notion of evolution, while our own gaze falls on this meeting of childish spontaneity and scientific order: the world reduced to models and specimens. Finally, there is her image of the head of an anatomical model: one half of the face has been peeled back and opened up; the other half is sad and tearful. All these works, many of which are grouped into series with different perspectives, throw up questions: Who is looking? What are they looking at? Who has commissioned this, installed it, arranged it this way? These are questions about the order and power of seeing (Michel Foucault), about the categorization of nature and the desire for control.

In her images of display cases or window displays, Zoe Leonard shows us little stages of varying sizes on which the norms of society and the power of science are played out. Here, the hard metal forms of the showcases clash with the organic natural forms of the exhibits inside. The specific approach of these photographs builds up a series of visual contrasts between hard and soft, constructed and natural, geometric and figurative, resulting in a kind of “aggression gap” between the installation itself and the nature of what is installed.

The theme of seeing culminates in two mirror images—photographs of opulently framed mirrors against sumptuous wallpaper. As explicit, expansive instruments of seeing and mis-seeing, the mirrors become symbolic. While a beam of light falls on the mirror, its frame and the wallpaper, illuminating the gilding (the pool of light on the wallpaper frames the mirrors, turning them into objects of desire), the slight angle of the mirror prevents a direct reflection, which might lead the eye elsewhere. Instead, the gaze is channeled out into the beyond. Seeing becomes a solemn, yet complex, broken and inscrutable cultural act.

In the field of tension between photographic material and the photographic act (between seeing and recording an image) Zoe Leonard develops her themes in an indirect, discursive way. The view of the world from above is seen as a body with arteries, with roads and waterways; the world as a model, a notion, a plan. She gives us a view of the relationship between the sexes (strange appliances and instruments, clothes and fragments of text; the female sex in the context of male-dominated European painting). She gives us a view of the relationship between culture and nature, with the hunting trophy as a (shabby) sign of victory and supremacy; with urban trees, caught in the struggle between natural growth and the encroachment of urban constraints; with the nest as a fragile, exposed place of procreation, and in the foraging of food, wrested from nature, blossoming and then withering.

Looking at the aerial images in which Zoe looks down on to the world is like sitting in a hot-air balloon or a small aircraft that has drifted upwards on the breeze until the world loses its tangible quality and appears to become a mere system of signs, or has dropped so low it seems we are about to land, as if we could pluck a handful of grass as we float by if only we could lean out of the window far enough. And then the angle is tipped, our gaze shifts, listing downwards. We see the Niagara Falls, with its volatile mix of glittering beauty and roiling, rushing power—this giant gash in the earth’s crust where the hurtling waters toss a tourists’ boat like a cork. We look down on the roads and railways that crisscross the earth—the grids and loops of modern, urban life, ordering our daily existence. We look into the volcanic glow of Parisian streets by night, into the urban lava streams of energy and traffic, into the lines and scars incized on the earth’s surface, traces of the lives we lead. These traces transform themselves into maps and urban models, into folded systems and visual thought structures. Zoe Leonard ́s images make a fuzzy cartography, both abstract and precise, distant and within reach; they bridge the gap between the unknowable and the tangible and seem to formulate a new dimension of seeing and understanding. In the case of the maps and street plans, the surfaces of the print and the surfaces of the map play off one another in a subtle interchange, forming secondary representations, peaks and troughs, in the light and shade of their folds.

This view of maps and models, of geographical constructs, complement Zoe Leonard’s photographs of museums, display cases, showcases and their contents in a way that gives us an insight into the ordering of memory, history and the various structures of knowledge and science. It takes us from a geographic view to a spatial order and culture, and all the while the questions are there: What is retained and preserved? How is it shown? How do we handle these goods? Who collects, who orders, who decides?

In one of her series of photographs of anatomical wax models, the female figure laid out on a draped cloth, her head tilted back, a necklace at her throat, evokes a bewildering mix of reason and emotion, clarity and melancholy. Bathed in light, yet dark, she suggests a willing victim, a sacrificial lamb. In another photograph this same figure, with her long shaggy pubic hair, encased in her glass box appears to be standing in a stairwell. In its stringent handling of space, this might be an architectural photograph, but the body is round and soft, rather than modular. The contrast gives the picture an aggressive edge; the spatial situation seems to violate the figure. In these images the portrayal of nature is exposed to the rational model of structured thought, and the two clash violently. In a third image, another anatomical model is seated, naked, on a chair draped with a light cloth, in a perfectly struck chaste pose. Her head is turned to one side, her arm raised, shielding her face against the gaze of others, while her body is naked, her viscera exposed. In her coyness, she becomes a dual object: an object of scientific knowledge and object of the (male) gaze. She is sealed inside a padded box, from which even the most tentative outcry against the power of knowledge would be stifled.

In her series of fashion show photographs, models strut before us along the catwalk and before the cameras that surround them in “real life”. We are watching a parade of seduction, a struggle of the sexes, acted out beneath massive chandeliers. Our eyes meet: they look down; we can see up their skirts, we can see the photographers snapping at the sides of the catwalk like a pack of wolves. Who is the instrument of whom in this elaborate and highly charged social construct?

Chastity Belt (1990/1993), Gynecological Instruments (1993) and Beauty Calibrator (1993) focus on the theme of controlling and manipulating the female body, on using tools to determine beauty. The beauty calibrator, an instrument developed by Max Factor in 1932, was meant to measure beauty precisely, to the millimeter. It could determine beauty on the basis of facial symmetry and other measurements of the head and neck. Early technical manipulations of the human body for the purposes of shaping, protecting or controlling, are a throwback to Johann Caspar Lavater and the physiognomists, while at the same time they refer to the latest technological developments of the digital age aimed at perfecting images of women and the rest of the world.

Zoe Leonard’s visual discussion of gender was catapulted into public awareness at Documenta IX, in 1992, where she made an active intervention into an exhibition at the Neues Museum in Kassel. She removed all the paintings from previous centuries that did not have a female figure as the central subject and replaced them with small black-and-white photographs of female genitalia, hung against the ornate pastel-colored wallpaper. The contrast could not have been greater: from the painted image to the photographic image, from rich colors to black and white, from canvas and opulent framing to simple prints under glass fixed directly to the wall. Instead of paintings of male faces, there were photographs of female pudenda, as individual as a second face, as free and open as though they were acting out the ultimate emancipation. For the 100 days of the documenta, these photos scattered in among the female portraits transformed this traditionally male-dominated domain of painting into a “women’s refuge”, representing female sexuality and female existence.

Strange Fruits (1992–1997) is the title of a sculptural work in which Zoe Leonard took the discarded skins of peeled fruit and put them back together again, sewing them or zipping them; some 300 oranges, bananas, lemons and grapefruit. Their contents had been eaten, their skins had dried up. The individual fragments have been reconstructed, but they have little in common with the preserved models in the natural history and medical museums. They follow a different logic. They tell of their emptiness and the passage of time. Not preserved in any way, they continue to shrivel and decompose. In this respect, they are portraits of decay. Zoe Leonard also uses the idea of decay in her photographs of apple trees laden with bright orange or red apples, which seem to glow all the more because the trees have lost their leaves. What remains is the winter starkness of the tree, against which the brightly colored fruit become symbols of the cycle of energy that waxes and wanes; of procreation and decline. In her series of photographs of nests, with one, two or three eggs, surrounded by scrubby grass—sheltered and yet vulnerable, protected yet fragile—we recognize the profligate squandering of nature. This fragile “fruit”, produced and protected, nevertheless seems exposed, defenceless and abandoned.

Fruits of another kind appear in her hunting series. These photographs of hunted and killed animals reveal a world of others, a world of power. A paw on a skinned leg is hung on a line like a trophy, against a shimmering, almost lovely background. Yet all the signs in the photograph indicate a natural food chain of hunting and gathering in which the animal is a victim of use, part of the need to survive. After taking part in Documenta IX, Zoe Leonard spent two years in Alaska. Her image Bear Head on Ground (1996/1998), a solitary head lying in the straw, its tongue hanging out, is almost surreal. The dance is over, the bear’s power broken. The body of a dead beaver, floating in calm, indifferent, milky waters, with two footprints visible in the mud nearby, suggests an act of unequal power. Finally, there is the belly of a beaver, its entrails exposed, a lurid image, but the surgical precision with which it has been slit open is coldly expressive.

The trophies tell of a struggle in nature, red in tooth and claw, just as the photographs tell of an inner struggle with the medium itself. Zoe Leonard molds her material like clay, like a Giacometti of photography. For all their documentary simplicity, her images are an amalgam of seeing, thinking about and feeling the world. Her photograph is more than just a documentary fragment, it is an autonomous whole, which in its totality speaks of the world, of photography and of Zoe Leonard. Her pictures of trees, with their boundaries and fences, evoke the ambivalent struggle with the world and the coming to terms with it. Tree and fence merge together in a continued, rambling growth, becoming one like the object observed and: the desire to understand it; like structure and knowledge; a weaving together of nature and culture.

Zoe Leonard photographs over long periods and extensively, and when she finds an idea, she circumscribes it, looks at her subject matter from different angles and viewpoints, addresses many different perspectives. Her images trickle down through the sediment of time and space, passing through a phase of endurance, of shaping and reformulation—a process of distancing and internalizing—until the subject matter opens up and reveals itself. During the nine years that her new major work Analogue took to create, it evolved on the pavements of Manhattan and Brooklyn, while she looked, as observantly and patiently as Atget in Paris, into the windows and shop displays, and at the commercial signage, until she had eventually created a vast portrait of global change, a visual record of economic and social transformation in which established habits and business principles have been eroded. Her images lurch and veer, they group together in series, covering the spectrum from retail to wholesale to service industries, to supply and demand in the marketplaces of the so-called Third World. They chart the tortuous progress of emerging markets, revealing the inherent traces of commodity trading in the visible world of consumerism. Analogue is a work that deals with ideas of plenitude and imperfection; it is a woven fabric with finished areas and threadbare gaps, transforming its own underlying concept as it progresses, shifting and adjusting its viewpoint as it moves through the world, without ever losing touch with its own guiding principle, its basis, its own time.

Zoe Leonard follows the traces and scars of the world in order to understand the structures of the world, to comprehend the essence of past and present, space and time, existential and social relativity. This is what saturates every aspect of her photographic work. She records with an eye that is both subversive in its questioning and almost casual in the way it reveals; she abandons and reprises until the form of the image is resolved, which is to say, until the view, the material and the subject matter are totally one, as inseparably melded as chewing gum on asphalt.