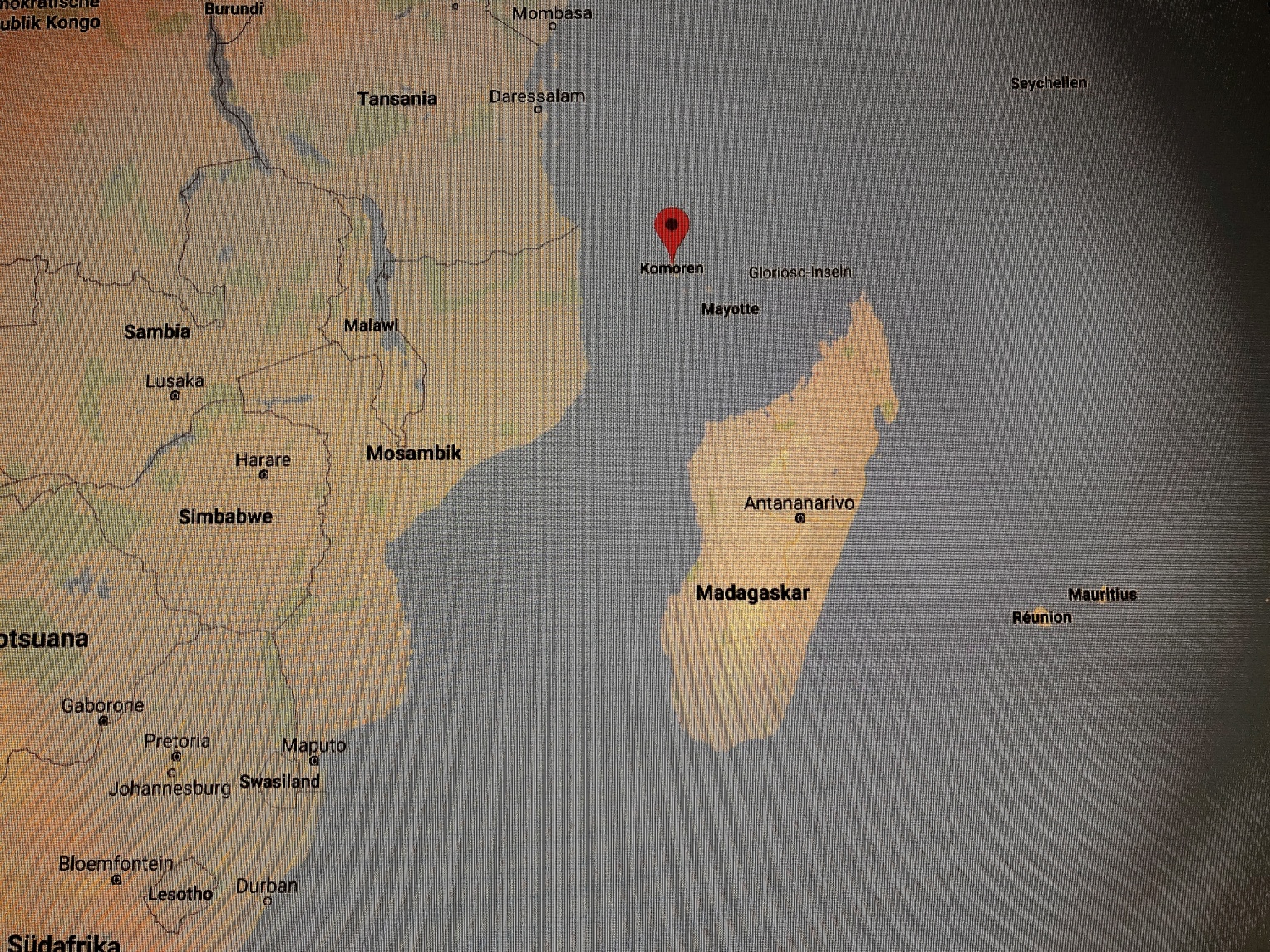

Comoros Encounters – this is the core concept of the exhibition and the work by Kelvin Haizel for A New Gaze 2019. Haizel, who hails from from Ghana’s capital city, Acccra, headed to the Comoro Islands to engage as an artist with the way of life there, including the prevailing economic and political structures. He flew from West Africa across southern East Africa and on to the archipelago that lies off the coast of the continent, just north of Madagascar, comprising the three main islands of Grande Comore, Anjouan and Mohéli, which together make up the federal republic that gained independence from France in 1975, and the fourth island, Mayotte, which, since 2014, has held the status of 101st département of the former colonial power, France.

Encounters – concordant and discordant – with an economically and politically complex postcolonial situation made it impossible for the artist to visit all the main islands when he first went there. A visa had to be purchased in order to visit Mayotte, This is a hurdle that all Comorians have to overcome just to visit their neighbouring island. It inolves an encounter with an economically precarious and even pitiful situation. The GDP of Mayotte is just one quarter of that of France, while the GDP of the other three Comoro Islands is thirteen times lower than that of Mayotte, making it just one fiftieth of French GDP. Astonishingly, things are even worse in Madagascar, slightly further to the south. Admittedly, GDP is by no means a measure of happiness. Encounters are also made between theory and practice, between the clariity of theoretical approaches and the diverse range of issues to be found in the real-life situation.

By engaging with these diverse encounters, Kelvin Haizel came up with some surprising and profoundly insightful connections. Take, for example, BASIC I and BASIC II, which form a complex large-scale installation on the ground floor. These titles form acronyms that summarize the main title: Babysitting a Shark in a Coldroom. The artist himself appears, dressed in a white robe, a tunic, with blue rubber gloves, holding a little shark as though “babysitting” it. In the larger-format photographs he is also wearing a red-patterened cloth around his midriff. The smaller-format photographs, on the other hand, are cropped into an oval shape reminiscent of airplane windows. On the monitors of two aircraft seats, there are excerpts from a video of an emergency landing on water. All of this plays out before a bright green background. The performance appears at once clinical and yet at the same time almost as surreal as Man Ray’s Chance Encounter of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella on a Dissecting Table – the photographic embodiment of a famous quote by Lautréamont describing the beauty of a young boy – in an absurd metaphor that was subsequently adopted by the Surrealists. Here, Haizel links the the ditching of Ethiopian Airlines flight 961 off the Comoros in 1996 with the economic and political situation of the archipelago. The plane had been flying from Addis Abeba in Ethiopa to Abijan in the republic of Côte d'Ivoire when it was hijacked by three Ethopians who ordered the pilot to fly to Australia. With fuel running out, the aircraft plunged into the sea. 50 of the 175 passengers on board survived. The bodies were brought into a large coldroom that normally served as a refrigeration space for the entire island, and laid out there. Ever since, this room, desecrated by the event, has remained abandoned within the urban fabric. It is here that Haizel performs with the shark that he bought from a local fisherman, deploying the blue, white and red of the French tricolore to represent the former colonial power. He describes the performance as “a fictive re-membering of a historic event”. The bright green screen against which the photo-performance takes place indicates the possibility that the image generated here can be contextualized almost arbitrarily in different ways at different times.

The series PROOF – Possibilities of Our Return presents a series of posed portraits, mostly seated, against a gray cloth background with a reflective black table, as well as two full-figure portraits in long white robes (kanzus), surrounded by radiant orange. Here, Kelvin Haizel references the backstory of an acquaintance who had lost his brother three months previously and he develops this narrative into an instrumentarium consisting of various props that he uses to create potraits as compelling as they are enigmatic. The brother of his friend had been a farmer and fisherman, like so many on these islands, and had been lost at sea. The mask Haizel wears is made of cloves—a crucial island product—while the orange jackets of the marine rescue service appear either realistically or simply as an orange color field. The globe and the map, on the other hand, charting both the global and local geography, tell of the islands’ geopolitical situation. Individual titles in this group include Gloves, Cloves and the Globe as well as Gloves, Cloves, Cheers and Orange is the Colour of Hope. Here, too, as in the first series, the artist alienates the scene, breaks down the events, opens everything up, so that in spite of the searing symbolism, there is is a free encounter between the viewer and the viewed. In another group of works, he uses cloves and ylang-ylang (a highly prized fragrant plant used as an essential oil in the perfume industry), to point out the limited resources by which the islanders earn a living..

The third core group, Every Other is a Citizen, highlights the archipelago’s migration crisis, which has escalated in recent years to levels similar to those in the Mediterranean, especially since Mayotte, which is French, introduced a mandatory visa system. Many Comorians seek to reach Mayotte, because the poverty of their islands is so extreme. Those who manage to get there tend to do so illegally, in flimsy boats, when the sea is not too rough, the boats not too full, and the encounters with the French coastguard not too dramatic. Once they reach their destination, they face years of struggling through tortuous asylum application processes. Certainly some 30,000 people have already died attempting the crossing. Kelvin Haizel writes: “… after legally acquiring a visa to Mayotte, I created this series. I photographed people who are in Mayotte as asylum seekers, Comorians who have been denied visa to Mayotte, or those who haven’t even dared to try. These pictures were superimposed on the visa I acquired and details were changed for each image. I chose the immigration booth aesthetic because it puts the images in a site reminiscent of where its politics play out.” The portraits he uses here show some of the men and women he encountered. Many of the women wear the typical Comorian coral-paste mask that is used both as a beauty treatment and as an embellishment.

These three major groups of works are anchored by a backdrop of two walls of pictures: Boats and Blues between Land and This Cannot Be Delicious Forever. The first cloudlike group of photographs outlines the topic geographically, showing encounters that illustrate where and how the fishermen of the islands work, while the second group sets out the social background, encompassing the architectural and social fabric, such as the socially immensely important “grand marriage”. Both of these groups of works are remarkably sculptural. The Boats and Blues wall appears as an uneasily built whitewashed brick wall, weathered by wind and salt, while the social images are immaculately mounted on board in clear-cut lines as though arranged on a domestic altar or in some public place of remembrance. As visual backdrops depicting the geographic, social and economic fabric of the Comoros, they form the green screen of the exhibition.

Throughout the entirety of Babysitting a Shark in a Coldroom what we find is the gaze of an artist supremely capable of underpinning his various encounters with the social, political and economic situation of the Comoros by means of a deeply complex visual discourse that not only reveals the visual worlds he has created, but also alienates them by making them into “objects” and physical “intruders” entering our tangible reality. He creates images that are wandering migrants in our world of experience – a meeting, a clash, of “image” and “reality”, a coming together, an encounter of two mutually influential worlds.