Architecture is indeed a game for the eye to play; we look, and, as we take it all in, we probably do so primarily physically. We might say, “I feel boxed in here”, or “I don’t feel comfortable here”, or “this is a good place to talk”. These are the kinds of snap judgments we make about rooms and spaces once the feedback from our senses has given us an overall impression. In doing so, what Goethe described as our “blunt” tactile senses play a role just as important, perhaps even more so, than that of our visual senses. We may think we see with the eyes alone, but we also “see” with the body; we wander through rooms and corridors and buildings noting a certain smell or a feeling that the materials and dimensions give us. We get a sense of whether we can breathe freely in a space, or feel suffocated by it, whether the proportions seem harmonious or distracting, as though they were tugging at us, stretching us, oppressing us. Our feelings and perceptions respond directly and immediately to whatever atmosphere the architecture may exude.

In Paul Valéry‘s Eupalinos, Phaedrus and Socrates have a discussion in Hades about the architect Eupalinos, his work and his thinking. They express their discontent at the fact that they, as dead people, can no longer fully participate in the uniqueness of physical and material beauty, which Eupalinos describes in terms of the perfection of form, matter, architectural ideas and their realisation. Freed from the burden of their mortal bodies, Phaedrus and Socrates should really be in an ideal position to appreciate beauty. After all, in his Phaedrus dialogue, Plato maintained that “we are imprisoned in the body, like an oyster in his shell” and therefore incapable of truly accomplishing our loftiest desires. What a disappointment then for the soul without a body to be capable of recognising beauty but unable to experience it physically. And so, according to Eupalinos, some buildings are mute, others speak, and others actually sing: but it is only when ideas and materials are melded through perfect craftsmanship that buildings become resonating bodies of musicality and lyricism.

Buildings are indeed bodies that we enter, walking into them for all manner of reasons; they are dwellings and shelters. We think and work in them, live and sleep in them. We explore them, study them, feel them, sense them as we move through them. And, on entering them, we notice the tonality of the architecture either subconsciously or as though on high alert. Our bodies combine with these other bodies or feel magnetically repulsed by them. We live with them, or in spite of them, and sometimes we find them remarkably neutral.

The history of Western architecture charts a path from squat, rough, thick-walled volumes to slender, smooth, elongated forms. Many traditional houses in the Engadine region of Switzerland have walls as thick as one or two metres – as though built to withstand landslides and rock falls. Steel and glass buildings, on the other hand, are often so delicate that the people inside have a sense of being outside, as though the comfort of enclosure had been replaced by a sense of exposure. Two worlds divided only by the thickness of a pane of composite glass.

The most radical thinning of architectural bodies occurs in the way that architecture is portrayed. The mass, the materiality, stands in contrast to their (ultra-flat) images. Buildings are imagined, invented, drawn, and – since the advent of the medium – endlessly photographed. The very first photographs were, without exception, images of architecture. Buildings take on a second, parallel existence in images; images that tell of their existence before, during and after, and which embellish them with thoughts, fantasies and ideologies. In the course of the centuries, buildings have become increasingly delicate and ever more slender, to the point of transparency, rather like the people who live in them. Yet it was images that first dematerialised architecture, reducing it to forms and signs. Oliver Wendell Holmes’s euphoric vision, in the early days of photography, of a world that could be experienced through form alone, entirely divorced from matter, and even burned down, gradually came to fruition, first in analogue photography and then especially in the digital age of virtual “reality”: the long path from substance to surface; from matter to sign. Even though, in the end, there has been no destruction of matter itself.

Pictures speak a language of their own. They offer a discourse that is unlike the physical experience of architecture. They transform volume into surface; distil matter into forms and signs. Photography shapes architecture, enlarging and reducing it, heightening and shortening it, accentuating it, yet rarely leaving it to its own devices. That is probably why so many architects try to get involved in determining the image of their buildings. The classic architectural photographer is their instrument, following their instructions, photographing the building at the zero hour as soon as it has been completed, cleaned and prepared – before any signs of use emerge, and before the building is occupied and transformed through use. That zero hour is the crucial moment of classic architectural photography. That zero hour is a building’s own. Within this brief space of time, architecture shows its ideal side, just as the architect intended the building or ensemble of buildings to look. Depending on the photographer, the building’s lucidity, transparency or spatial context is highlighted. Or it is presented as a new icon, to be featured in architectural journals. A moment of rapture, of detachment from reality, before the architecture actually becomes “used”, before it becomes a functional and functioning building, as in Roland Barthes’ famous example of trousers.

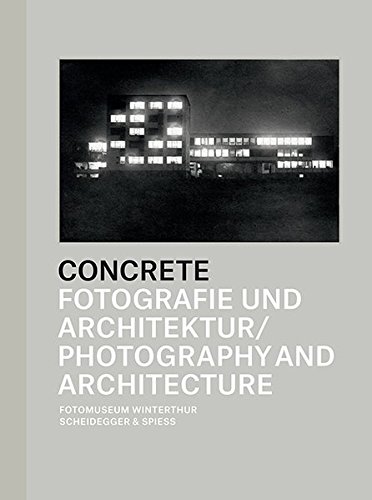

Buildings have a number of functions, primary and secondary. Some exist only in photographic form. Images may convey a building’s status or prestige, transforming architecture into brands, lending buildings a permanence far beyond their original intent, and even beyond their deliberate or accidental destruction, thereby retaining buildings and entire cities in the collective memory as a part of history once they no longer exist. This exhibition and book seek to approach the singular and complex relationship between architecture and photography in light-hearted, narrative and dialectical ways. We explore issues of history and ideology, as well as the specifics of form and material, in the photographic image. The visual appeal of destroyed or decayed buildings is also addressed, as are their lasting demonstrations of power and exclusivity, fragility and beauty. To what extent does photography influence not only the way architecture is perceived, but also the way it is designed? How does an image bring architecture to life, and at what point does it become uncanny [unheimlich]? How do settlements develop into cities? Or, in sociological terms: how do work and life interconnect differently in, say, Zürich and Winterthur, as opposed to, say, Calcutta or Chandigarh? And how do skyscrapers and living spaces translate into the flat, two-dimensional world of photography?

Architecture has always been an important platform for the frequently heated discussion of ideas and views, zeitgeist and weltanschauung, everyday life and aesthetics. Architecture is the bold materialisation of private and public visions, both functional and avant-garde art alike. It is, as Slavoj Žižek puts it, ideology in stone. Photography and architecture both play an undisputed role in our everyday lives. They confront us on a daily basis, often without our even noticing, and they influence how we think, act and live in subliminal and lasting ways. Concrete – Photography and Architecture provides visual answers to the question of what it is that makes up the intimate yet complex relationship between architecture and photography, architect and photographer.