The word “thing” (German Ding), now generally used in the sense of “object” or “article,” comes from the language of Germanic law, and originally referred to the law-court, the assembly of freemen. In Old High German it took the form thing or ding, in Middle High German dinc. Today “thing” and “things” refer to rather unimportant or lowly objects.1 What is fascinating is what an important, even weighty matter this word once stood for—an assembly of freemen constituting a court of law—and how the same word today refers, at least in ordinary speech, to something rather trivial. Such gradual devaluation in the meaning of a word is something frequently observed. For a long time the Middle High German vrouwe meant “mistress” or “lady of rank,” but now it has become simply the neutral designation for “an adult female, a wife,” having taken the place of the earlier wip.2 In this devalution it also reflects a change in the meaning of things for us. In the Middle Ages many objects were not only useful but necessary for one’s livelihood. If we imagine the “freemen” trying the case of a stolen axe, then an object was being debated before the thing, or law-court, that shaped a man’s whole life. The axe was one of the few objects, made by hand, that this man found essential, one that accompanied him throughout his life, even made it possible. Today, though we would be annoyed about such a theft, we would simply go to the store and buy a new one—or better yet a chain saw, much easier to use. Our relationship to functional objects, to our computers, for example, has become pragmatic: we use them as a rule without any particular emotion. So long as they are perceived as purely utilitarian, they can be replaced at will.

Ever since painting took up the depiction of objects—aside from representations of religious objects, this occurred on a wholesale basis for the first time in Dutch painting of the seventeenth century, where acquired possessions are introduced into pictures of interiors—it has been possible to divide pictures between those depicting an ordinary, meager, essential object—a plate, a carafe, a knife and fork on a simple wooden table—and those presenting objects as attainments, whose abundance, even opulence, is understood to be symbolic of success and status-consciousness (within an awakening bourgeoisie). The American photographer Paul Outerbridge has pursued both genres in his photographs. Alongside photographs presenting plain, simple interiors in the Quaker style in muted browns, there are color photographs of laid tables, gift tables, and Christmas trees of the most lavish splendor, lent a touch of solemnity, as though with the addition of heavy silk, by the Carbro color process. Here there is an obvious distinction between essential things and beautiful ones—with a nod in other photographs to yet a third genre giving objects a metaphysical significance through their arrangement. The object before me, the world of objects in general, sets me to thinking, seduces me into meditating on the relationship between subject and object. And here the object can at times become far too animated—“But tell me, what are you staring at so madly, do you see ghosts?”3—can distort itself on its own or owing to its arrangement, and take on importance for me beyond its material and form. One thinks of poor Theodor in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s night-piece “Das öde Haus” (“The Deserted House”), who thinks he sees a “lovely visage” in an old abandoned dwelling, and afterward, seated on a bench, cannot stop staring at it.4

People have always felt somewhat ambivalent about the world of things, objects produced by hand and acquired. A single jackknife, a single bicycle, a single globe suffices—so long as the knife works. “What more do I need?” Owning two or more identical objects, or great numbers of them, has been somehow suspect (unless you are a passionate collector). Over the centuries, possessions have always been a mark of class. Noblemen and noblewomen, people of a certain station, factory owners, wealthy merchants, and the earliest bankers lived surrounded by opulent objects. In contrast to such furnishings, representative of actual situations, stood the empty lives of Gerhard Hauptmann’s Weavers or the peasant lives full of privation seen in paintings by Jean-François Millet. The Catholic Church responded to the Protestant Reformation, which was after all a revolution through asceticism, a turning away from rich, luxurious baubles in the context of religion, with almost aggressive baroque opulence, as if it hoped, paradoxically, to put down the new voluntary penury and iconoclasm with an overabundance of ornament.

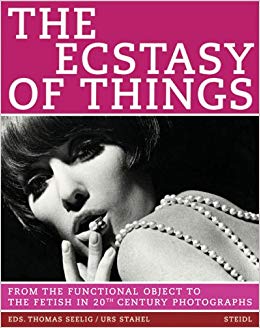

In the twentieth century, and especially its last decades, our relationship to things has fundamentally changed. In his essay “On the Poetics of Things in Modernism,” Michael Jakob here writes how completely natural products, highly prized from the Renaissance up to the Enlightenment, have been supplanted by manufactured things, mass-production goods. Mass production democratizes ownership of objects, makes them affordable to many—the trade-off being that they are no longer special, no longer unique, but have to rely on their glint of newness for their appeal.5 Mass production was forward-looking from the start: with new, sleek functional objects purged of their historical forms and their bourgeois, nineteenth-century showy connotations, the world, the way we relate to the world, would be changed. Schools for designers with high educational ideals shot up all over. However, the economic situation between the two world wars forced designers to work with simple, inexpensive materials, which at first tended to obscure the change that was underway. This limitation fell away in the second half of the century. Rapid growth of the economy, of prosperity, of the purchasing power of the individual allowed the cycle of production and consumption to expand, to become at one and the same time larger, more inclusive, and faster. Gradually, at first, then rapidly and exponentially, a culture of needs was transformed into a culture of consumption. Shopping has become a hobby, one that is now listed in personal ads as a personality trait—its dark side is compulsive buying. Ordinary stores have been transformed into worlds of adventure, into shopping malls whose offerings are thinned out by the Saturday hordes. A fifth of what they buy ends up in the trash, unopened. Statistics tell us that four-fifths of the remainder is either thrown out, given away, or resold after a single use. On the home pages of Internet merchandisers an offer to immediately sell in the same marketplace the goods you just purchased pops up the minute you click on the button confirming the sale. Consumer intoxication and the compulsion to consume: we are able consume, and we are driven to. Newspapers no longer offer the “item of the month” but rather the “fetish of the month.” Things become a cult, “lifestyle” overshadows how we feel about the world. We are caught up in an “The Ecstasy of Things.”

To the degree that attention to and care of individual objects are being lost, things in general appear to become more important to us. Norbert Bolz points out in his lecture how great is our need for fetishes in the absence of deeper meaning in our lives. “You are the devotee of some object, some cause, some ritual in which you find the security, the behavioral and existential certainties that the cultural perspective of our enlightened way of life has failed to provide.” And people today, he continues, expect a spiritual add-on in these goods: “They want a product that is loaded with meaning, with a kind of sensual promise, the kind of sensuality that formerly adhered to religious symbols.”6 The dividing line between people and things is becoming indistinct.

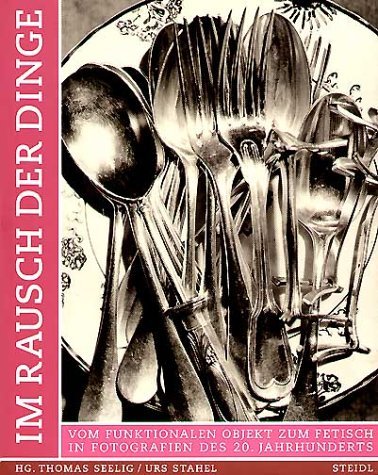

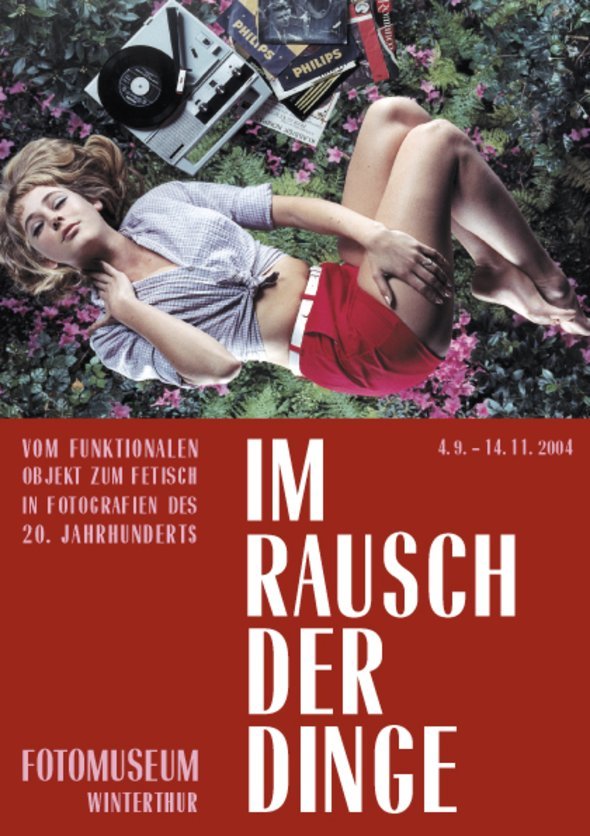

It is from this perspective that we here look back on the twentieth century. We look at the variety of things, objects, articles, products, toys, utensils, and machines that were creatively designed and mass-produced. Study photographs of things, from design to production, from merchandizing to use, from functional objects to object fetishes. We are less interested in the charmingly arranged still life than in the display, offering, advertising, introduction, and presentation of things. The photographs reflect contacts with objects made by people for people—a relationship that falls into a faster and faster spinning cycle, as though we could no longer bear repose and consistency. Photography has played a major part in this expansion and acceleration. Whether things are shown in shadow—meant to underscore their value—as is often the case with photographs from Spain, or a silver spoon is pictured against the backdrop of Versailles—because French photography tends to place things in landscapes to lend added meaning to them, or a white light switch is photographed simply and clearly, in virtually puristic severity before a monochrome background—as so often in German or Swiss photography: in every case the photograph introduces the thing, shows it off, sets it apart, emphasizes it, glorifies it. Not like ordinary photographs that at the click of the shutter fade into the immediate past, registering a passing moment. This kind of photography wishes to help things look their best, to lend them distinction in the present, and infuse them with future promise.

Some twenty researchers on this project traveled around Europe—Switzerland, Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Spain, Holland, Belgium, England, Ireland, Scandinavia—and the United States and Canada, that is to say the heart of the Western world, where the chain leading from design to production, to merchandizing, and to ultimate use can be seamlessly documented. They consulted company archives and designer, museum, and private collections in their search for photographs that reflect our contacts with things, whether in banal, impressive, or special, valuable ways. The shape of the project evolved out of this visual research in the field. It has become an exhibition and book project about things and their photographs—photography only theoretically admits a distinction between motif and image—about object photography and its issues, about advertising photogrphay and its products, about private documentation of the personal fetish.

We thank these researchers for their attentive, inquisitive searching. We thank the more than 150 lenders for their willingness to place their pictures at the disposal of the project, some of them to be seen for the first time. We thank the writers for their reflective, thought-provoking essays about things in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, about object photography, about basic concepts regarding the relationship between photography and things, about changes in materials. We thank Martin Jaeggi, who from his Berlin outpost not only wrote the fascinating chapter texts and translated and edited the essays, but remained a constantly attentive critic. We thank the UBS as the main sponsor of the project, and Canton Zürich and the Bundesamt für Kultur in Bern for their considerable support.

On to intoxication with things!

Notes:

1 Duden, vol. 7, Etymologie, Herkunftswörterbuch der deutschen Sprache, Mannheim, Vienna, and Zürich 1963.

2 Ibid.

3 E. T. A. Hoffmann, “Das öde Haus,” in: idem, Der Sandman; Das öde Haus, Stuttgart 1972, p. 59.

4 Ibid., pp. 43ff.

5 Michael Jakob, “On the Poetics of Modernism,” in this catalogue, p. XX.

6 Norbert Bolz, “Culture and Contingency,” in this catalogue, p. XX.