Nanna Hänninen’s works, until now, have been predominantly introspective. In them, she has directed her gaze from the outside world – as insistently visual in all its teeming heterogeneity as it is elusive in boundless richness and concatenations – towards a calm and clear inner world, towards the sparseness of a White Box situation, a white-in-white studio world that forms the pared-down background for small, minimal, concentrated interventions. Stepping out of the world in this way also meant renouncing subtraction – the eliminatory and orderering reduction that is a fundamental tenet of photography – in favour of addition as a compositional principle: building the visual world in an empty space. For this, Nanna Hänninen deployed a mix of sculptural, installative and photographic processes. She painstakingly placed element after element, object after object, into the stark white-in-white: round white dots geometrically arranged on a pastel ground; or three white shuttlecocks, their rounded black ends like eyeballs, telling of distillation and dissolution, of feathery lightness and earthbound heaviness; an airplane of folded white paper that seems like a fragile form peeling out of the white (primal) ground and hovering there; or wooden toothpicks closely aligned and rolled out into rows of sharp-tipped palisades; a stack of paper, carefully calibrated, ponderously placed on a wooden base; twelve white boxes stacked in a block as though air were being shaped and arranged; and finally, white paper envelopes, filled, sealed and set on each other like soft cushions.

In other words, Nanna Hänninen would place one object next to another with compositional economy until these few elements began, reticently, to tell us something; until the signs – in a balance of abstraction and concretion – gradually began to take on meaning. But it is in their photographic form that the objects and words become clearer, more legible and more metaphorical: when the depth of focus has determined which lines, which clips, which circles, which words are portrayed in sharp focus and which are blurred, when the angle of view has determined which object stands out prominently and which recedes into the background, and when the lighting has modulated the photographic space created by Hänninen. Only in this way – through the selection and alignment of the objects and through the determining gaze – do these deliberately simple and banal objects become representational, and the photographs are transformed into a visual imaging of Hänninen’s thoughts.

Some of her titles – such as Fear and Security, Keep under Control, Information Failure – affirm that her theatrically staged scenes are to be read as visual aphorisms, as emblematic concretions. In exemplary visual form, they formulate ‘thoughts’ on the fundamental and essential traits of individual and universal existence in the world, they ‘speak’ of tensions, contrasts, overload, error, order and loss of control. In her book Fear and Security, Nanna Hänninnen is quoted as saying: “Instead of order, I started to see chaos in things. I have been trying to catch the idea of society which is filing, sorting and systemizing things to be more secure and organized. I see a great paradox because by setting up security measures you cause insecurity of something unkown .... this series (Fear and Security) is about the fear of losing control.” It is evident that Nanna Hänninen’s works from this period give tangible expression to insecurity and the search for possible structures of order. As the old orders of the world disintegrate ever faster, we are faced with the question of how and which new orders will emerge and how the individual will relate to and be involved in them. Increasingly, the tangible material world is vaulted by the dome of a sky of immaterial signs – where do we chart our feelings in this new art-space and how are orientation and memory possible without the familiar visuality? The fear of losing control, the fear that things will slip from our grasp and turn against us: such are the mental and psychological states that Nanna Hänninen addressed in her cycles of concentrated, almost pure-white images that evoke both innocence and infinity, primal ground and placelessness, while at the same time exploring the components that are the building blocks of our world.

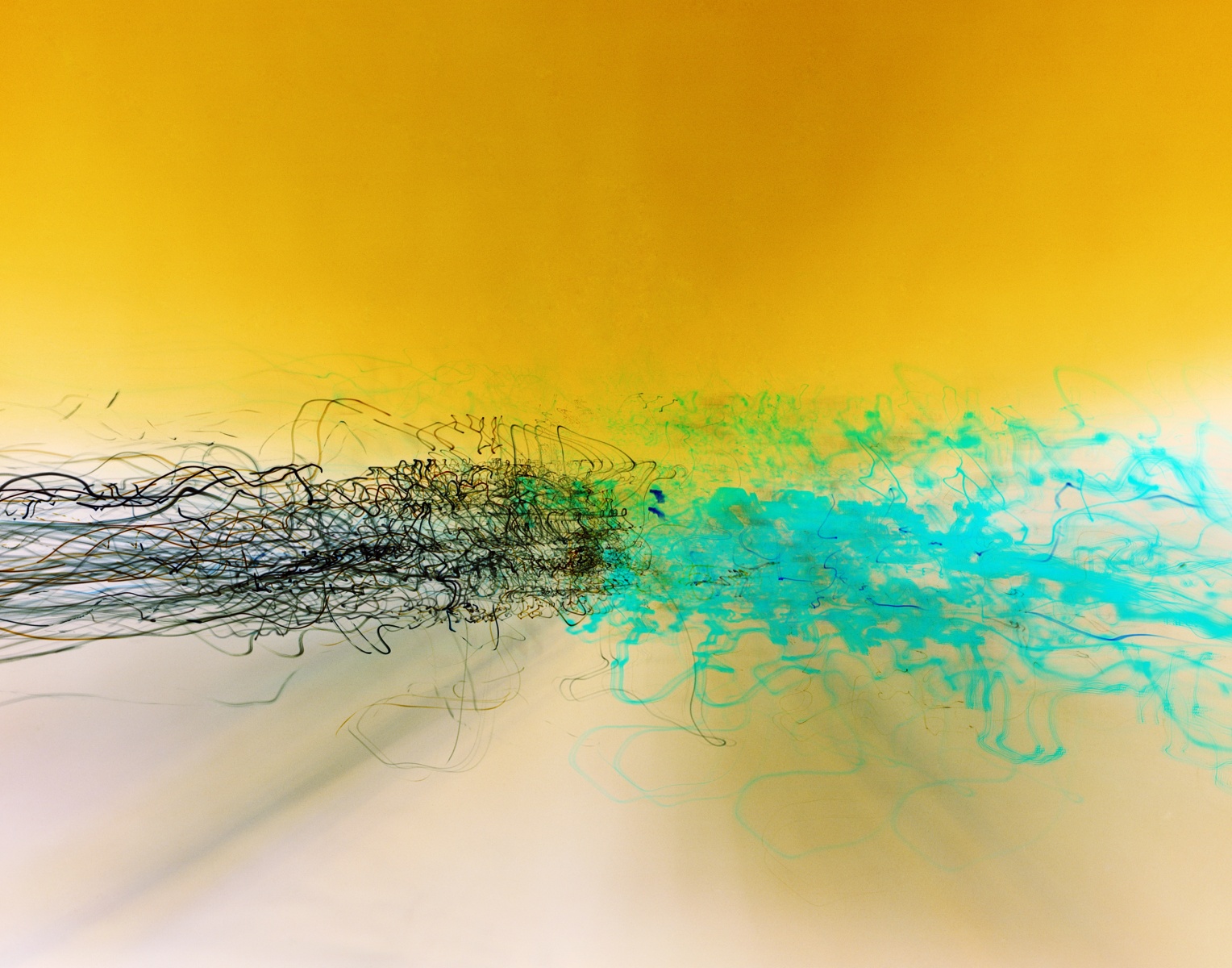

Nanna Hänninen formulated her journey to the inner world at what was almost the point zero of the photographic gaze. This in itself suggested that the closed space would one day be opened up. The way in which this has now happened in her latest works is, at first glance, bewildering. Although Nanna Hänninen is standing outside again, looking into the wider world around her, photographing places that can be named geographically – Basel, New York’s Brooklyn Bridge, the airport of Ponta Delgada, the port of Helsinki, the A5 autobahn – the results of these real and actual observations somehow seem more abstract than ever. Nanna Hänninen is there, physically present, in Zürich, in Manhattan, in Somewhere – whether on the move or quietly observing, she is in a place that really does exist. And she documents, with seismographic precision, the interplay between the movements of the real world before her eyes and her own world, her movements, her breathing and laughter, her hesitation. The intersection and catalyst of this new approach is a large-formate camera, a 4x5 inch plate camera, which Nanna Hänninen does not place on a tripod, as its weight and size demand, but which she holds in her hands. She does not keep the camera still, but allows it to move. The result is a constant intersecting of inward and outward movements, documenting parallel events simultaneously; the heartbeat of the world and the heartbeat of Nanna Hänninen meld in the camera. We follow the pulsing rhythm of intersecting energies and see the fallout from the artist’s own encounters with the world. The fluidity of the world and the fluidity of her life meet at a certain moment, precipitating something akin to a chemical fallout on the film. As a trace, as a memory, as a chronicle of events and their meeting with each other.

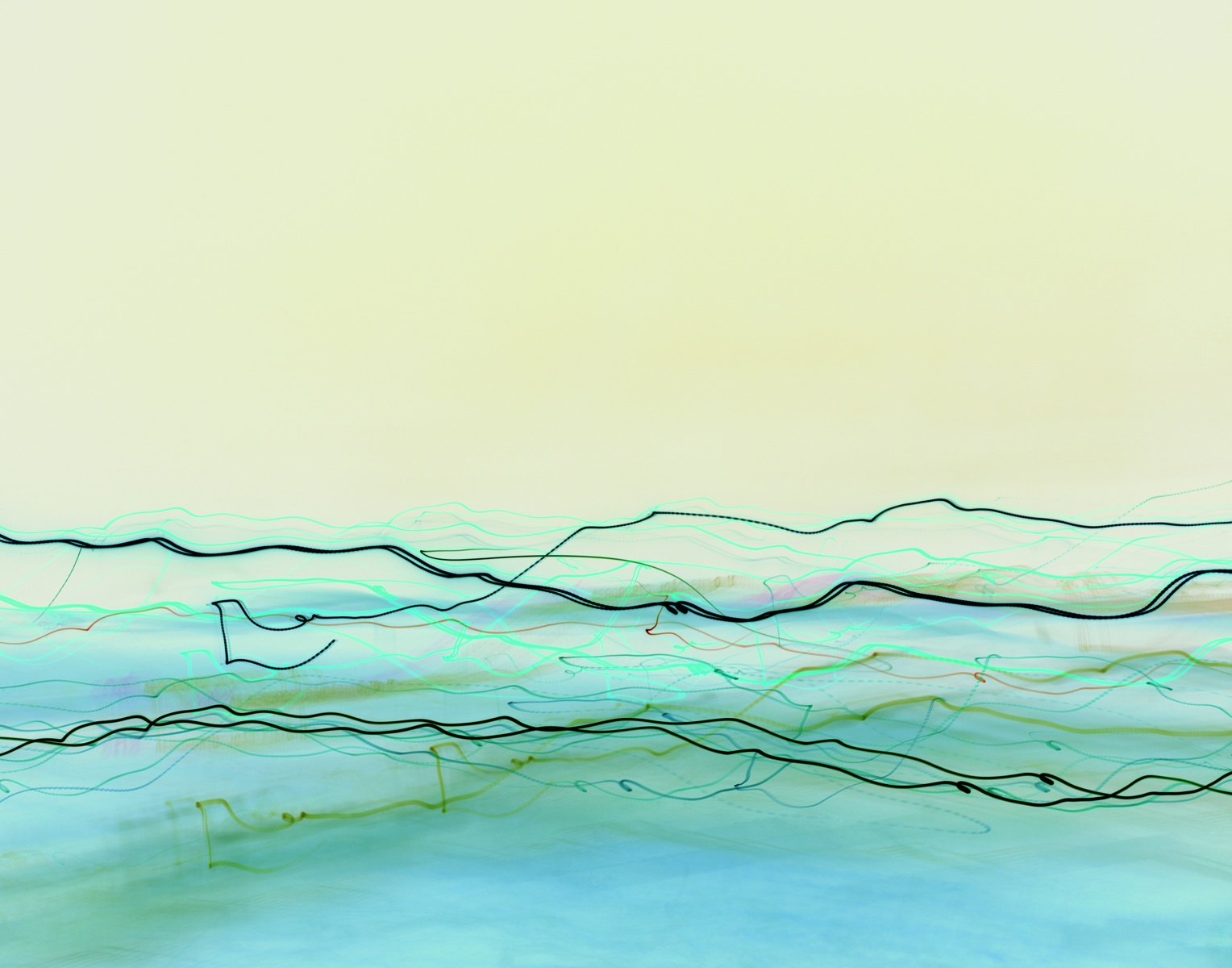

In other words, what we find here are highly abstract photographs with semi-translucent, intangible backgrounds and sketchy undulating movements, with lines contracting, expanding and entangling, with fields and clusters of colour – which, in painting, are indicative of the Informel, of the free and unstructured, pulsating (out)pouring of painting in the 1950s, and which, in the world of apparatus, measuring instruments, calibrating devices, cameras, is reminiscent of curve progression, of the documentation of earthquakes, heartbeats, blood pressure or pressure waves as they might appear on an electronic display. The lines that are left recall the cartography of landscape, with its precise contour lines, sometimes sweeping, sometimes angular. On the autobahn, by contrast, the lines converge more densely, more urgently, more intensely. The rapid forward movement creates a halting, (explosive) charge of energies, depending on the speed, as though we were hurtling towards a frothing mountain of colour that keeps on intensifying, even magnetising. Here, perspective seems to implode; it seems to overtake itself. Other lines play casually with our perceptions, bobbing figuratively across the picture plane like seahorses, only to disappear into nothing.

We follow these curves, these lines, grids, knots, nets, suspensions. Against the seemingly illuminated background, we perceive them as abstract landscape drawings that constantly remind us of music – as though an orchestra were playing here, as though many voices and sounds were converging, tracked by us at the control desk as a lively notation of the events and coincidences of the world, a rhythmic chronicle of energies, the seismograph of the city, of life.

And so, on her way out of the artificial photographic space into the wider world, and in spite of including her own emotions and viewpoints as she photographs, Nanna Hänninen’s work has become visually even more abstract and reduced than before. She concentrates on these interfaces between subject and object, between outer and inner world, between what objectively exists and what is subjectively perceived; she plays with the mix of outward and inward flow and presents us with a visual record that appears abstract but is freighted with specific events and their convergence. The lines appear artificial, fictitious, and yet they are real traces, concrete precipitations. In this process she generally works with photographic negatives, inverting the familiar image: what was light now seems dark, while the dark background shines as brightly as a monitor, like a candled membrane. In doing so, she distances herself from familiar perceptions, alienating them, transfiguring the world, making it appear like an electronic display with depth (not normally associated with such displays). And at the same time Nanna Hänninen breathes, laughs, moves, pauses: the picture is not still, as is usually the case in photography. The picture breathes with her. It is pulled and blurred as though peeling a transfer off the surface of the world. The result is a photographic image that tells of the world and of Nanna herself; an image that is abstract, transfigured, and yet strangely concrete and real.

In her new landscape images, what is inherently present in every photograph, but so often obscured with great effort (the shorter the exposure time and the greater the depth of focus, the more brilliantly the image blinds us to the medium and the production process behind it), becomes a tool by which to visualise different interfaces: the interfaces between the medium and the information it conveys, between the real world and its (mathematical, musical, analog and digital) image, between the abstract and figurative, between detached observation and involved on-looking, between subject and object, between the individual and the universal. Hänninen’s visual approach thus dispenses with that old philosophical appearance/reality chestnut epitomised by Wittgenstein’s refusing to accept that there was not a rhinoceros in the room: she presents the world as a meeting of simultaneities, a clash of energy fields, as a permanent, indissoluble and reciprocal intertwining of the self and the world – and of viewer and the work. The only reliable viewpoint from now on is one that is in motion. Static becomes dynamic. The intangible becomes more familiar than the tangible. Our vague inklings enhance our specific knowledge, our experiences enhance our thoughts. Thought-images become experience-images that seem to tell us that this complex interaction is not only fragile, but also permanent and ineluctable.