Two or three decades into the digital revolution, the post-industrial information age is well and truly here. It has taken hold in every branch of science, scholarship, business and industry, and even has us as individuals firmly in its grasp. There is no end in sight to the technological development and global linkup. ”Ars electronica”, the major annual forum for the discourse on electronic art, in Linz, Austria, has also noted that ”… the acceleration and intensification of the related social changes have already reached an extent that no longer holds the fascination of utopia, but has already become reality.”1

That includes Dolly, the famous Scottish sheep that outdid the cyborgs in biological terms, only to be exceeded itself by even bigger calves. It also includes the globalisation of industry and business that has made location a matter of choice, replacing the unexciting but reliable notion of ”home” and ”roots” by a cult of mobility, transforming heavy, cumbersome real estate into a commodity as light as a stock certificate and placing the decision-makers at a virtual distance from those who carry out their instructions. In the world wide web cultures clash and are pulverised at the click of a mouse, with scales of value, established patterns and cherished mores amalgamated into virtual realities (VRs) and new web cultures. According to migration and identity specialist Iain Chambers, when the latest digital Ragga mix is sent from Jamaica to London and then on to New York for remixing only to be played on a dancefloor in Kingston a few days later, no need is paid to customs duties or semantic uniformity.2 Finally, it also includes mass migration and the global circulation of people and goods, services, signs and information. News and commodities are shifted from everywhere to everywhere. Everything seems to be constantly on the move.3

The monitor lends itself as a symbol of this development. It is the new window, the sign of today, the panel picture of the twenty-first century – source of information, portal of yearning and balsam for the soul, all rolled into one. In other words, it is both symbol and instrument. This ”window” does not open up outwardly but, only projects inwardly, radiating in our faces like a self-illuminating screen that cuts off the primordial immediacy of sensual perception, blocking our view of the world, our insight into nature, and our ability to touch, smell and taste substances, increasing the distance from the former object of perception with the cool silence of technology so that even signs are displaced and floating in its opaque glass surface.

We are living in a borderline situation. We are stuck with our feet on the ground and at the same time we can touch the sky. We are here and we think ourselves elsewhere. We are this way and describe ourselves another way. Our bodies are stretched, our thoughts meandering and intertwined – by their own free will or (more often) pushed, pulled, forced. Richard Sennett describes the physical and intellectual flexibility demanded of the individual by the economy as ”drifting” – an aimless drifting that dissolves the classic career and the bonds of friendship and family, while devaluing place, city and continuity.4 He even wonders whether the destruction of the human character might be the inevitable outcome. According to Sennett, the prevailing sense of ”nothing long-term” has a disorienting effect on all action, dissolves the ties of trust and commitment and undermines the most important elements of self-esteem.5 The example he provides is that of Rico, the son of an acquaintance, whose career and life situation he describes as both successful and confused. Confused mainly because his new work lacks all principle and work ethos that he might pass on to his children. The children and the children’s children of all the Ricos and Ritas in the world may not even notice these forms of distortion and tension. They will surf and click without prejudice, floating and hovering, changing their homes and their friends but to the point of screen-burn and standstill phobia.

The situations and conditions that arise through this development, or rather, these quantum leaps, are often described as hybridisation. Normally, hybridisation is a term used to refer to the cross-cultivation of plants, such as apple trees, for instance. In the lexicon of the Lycée Montesquieu in Herblay, which I found on the internet (so that it no longer matters where Herblay is in geographic terms), hybridisation is defined as follows: ”The hybrid is an individual resulting from crossing two individuals of different genotypes or different species. Natural hybrids which are found in nature play an important evolutionary role in increasing genetic variety. Hybrids are also produced artificially by creating contact between the reproductive cells of different types of organisms.”6 Hybrids that are the result of deliberate cross-cultivation tend to be referred to positively in terms of improvement and refinement, whereas those that occur by chance are often described in derogatory terms as mongrels or ”bastards”. Hybridisation is therefore a process of mutation that is constantly occurring and has been encouraged down the ages. Today, we not only talk of ”hybrid seeds”, but also of ”hybrid engines”, ”hybrid architecture”, and even companies offer services described as ”hybrid”. In our context, hybrid is used to describe anything and everything that involves mixing and dissolving traditions and patterns of explanation (as Elisabeth Bronfen has pointed out), anything that links different discourses and technologies, realities, or the techniques of collage, sampling and bricolage, and anything that replaces location (as genius loci and place of origin) by movement and constant flexibility.

The transition from natural to artificial, from real to virtual, from analogue to digital and from homogeneous to heterotopic spaces (by which heterotopic means overlapping or layered and reciprocally ”observing” spaces within a space) has massively increased the potential for hybridity. ”Today’s culture is hybrid,” claims Elisabeth Bronfen, adding that ”We need not fool ourselves. Today it is no longer a question of whether we consider cultural hybridity something to aim for or not, but merely a question of how to handle it.”7 The ideas and achievements of genetic technology, neuro-science, networked intelligence, globalisation and economic and social restructuring have raised the question of the individual’s place within these networked artificial systems: In 1998, ”Ars electronica” postulated, ”To the extent to which the membranes of our body and thought are permeated by the elements of a networked artificially intelligent environment, this grows to a real entity … so that a clear decision is no longer possible in the sense of subject-object differentiation. The classic western model of the individual as an autonomous inward-looking entity is replaced by a hybrid, networked subjectivity…”8 Conventional coordination, especially the notion of hermetic, inward-looking entities, seems to be disintegrating. Previously reliable fundamental and determining single entities – I, you, identity, truth, right, reality or even nation – seem to multiply and take on a certain dynamism in networking. Who is ”I”? I am many – one today, another tomorrow, maybe or maybe not. At any rate, I am a subject entangled, networked, far removed from the once-vaunted autonomy.

What does this quantum leap mean for our existence, our perception, our self-image, our ethics? Can the hybrid be the life model of the future or is it a necessary evil, suffering, catastrophe? So far, it has been given little public consideration. Richard Sennett clearly sees certain dangers in it, especially of a psychological kind, for he assumes that character as we understand it today will suffer to the extent of possible destruction. In the German-speaking world there was a recent debate centred on the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, who said in his Elmauer Speech Regeln für den Menschenpark (Rules for the Human Park): ”Whether the long-term development will also lead to a genetic reform of species characteristics, whether a future anthropology will go as far as explicitly planning certain traits, whether humankind will be able to implement a shift from birth fatalism to optional birth and pre-natal selection – all these are questions, however vague and disturbing – that are beginning to emerge on the evolutionary horizon.”9 In this respect, Sloterdijk was suggesting that we should not be too hasty in condemning the new technological possibilities right from the start. France has had a similar debate centred on Michel Houellebecq’s Extension du Domaine de Lutte and Les Particules Elémentaires. In each case, the debate was triggered primarily by a sense of helplessness in the face of such a gigantic and rapid change of paradigm and is the expression of a situation that, until now, has not been perceived or grasped either intellectually or emotionally.

In America, on the other hand, the hybrid is often upheld as a new way out of the old, fossilised dichotomies of oppressor and oppressed, man and woman, perpetrator and victim. According to cultural theorist Homi K. Bhabha, ”Hybridity is a gesture of translation that keeps open the question of what it is to be Indian in Britain or a gay British artist in California – not open in the facile sense of there being ‘no closure’ but in the revisionary sense that these questions of home, identity, belonging are always open to negotiation, to be posed again from elsewhere, to become iterative, interrogative processes rather than imperative, identitarian designations … an art of the interstices.”10 Salman Rushdie has taken a similarly positive stance: ”Brought from one end of the world to another, we are ‘translated’ people. It is usually assumed that something is always lost in translation. I cling firmly to the idea that something can also be gained.”11 His novel The Satanic Verses shows ”the world through migrant eyes. The Satanic Verses celebrate hybridity, impurity, mixing, the transformation that arises from new and unexpected combinations of people, cultures, ideas, political matters, films, song. They delight in bastardisation and fear the absolutism of the pure. … This is the great opportunity that the mass migration of the world offers. … The Satantic Verses are in favour of change through amalgamation, change through combination.”12 In his understandable enthusiasm, Rushdie seems to forget that, for many people, mass migration has to do with force of circumstance rather than free choice or the ”love song for the bastard within ourselves.”

A far more one-dimensional aspect can be found in the movements that speak enthusiastically of Enhanced Real Life (ERL) and Extropy (meaning the use of new technologies for physical, intellectual, psychological and social improvement), Excarnation (the body becomes text and is transformed into data) and Transhumanist Times. All these take an unconditionally positive attitude to such new developments as increased lifespan, human genetic engineering, modelling and stylising, even overcoming the natural body.

Artists have always been attracted by hybridity, for it creates the potential tension within which a work of art can be developed and can unfold its ambiguous, scintillating presence. Yet for artists, too, the issues have changed radically. Elisabeth Bronfen makes this clear when, in reply to the question posed by artists before 1960 – ”How can I interpret this world of which I am a part? And what am I within it? – she poses another more topical question: ”What kind of world is this? What is to be done in it? Which of my selves should do it?”13 Nevertheless, the artists themselves are perhaps more capable than others of helping us to understand, experience and grasp this changing system.

Katrin Freisager, for example, in her large, seven-part frieze, takes a bold step towards artificiality. ”Living Dolls” presents beautiful, immaculate models floating on a light foam rubber background. Their sparse, semi-transparent and flesh-coloured clothing reduces their nudity and sexuality, neutralising it. The structure of the sequence – each figure occurs in two perspectives and two different constellations – dissolves the unique and the personal, with neither drama nor sentiment. We seem to be faced with new media beings, biologically enriched cyborgs, with a black being in their midst that appears alien while at the same time lending visual support to the parade of human artificiality.

Günther Selichar’s ”Screens, cold” present images of switched-off monitors that focus on the link between the means of portraying representational photography and the ideas of abstract, radical painting, through reflections on the presence and process of electronic media, When ”cold”, or switched off, the monitor embodies a cool, still monochrome, whereas when it is ”hot”, or switched on, it is the embodiment of talkativeness with hurried snippets of information. Smooth, stringent, cool photographs of monitors are shown by Selichar as what he calls ”interfaces between the gaze and the portrayed” but also interfaces between the concrete object and the monochrome surface, between the presentation of the medium and the representation of the hidden, between abstraction and synthesised portrayal close to reality, between visible impenetrability and invisible hidden infinity, accessible at a click. Selichar’s monitor pictures visualise this interface as a blinding abyss.

In his ”Night Arcs” the American David Deutsch explores the garishly lit backyards and squares of Los Angeles, the tension between dark night and bright light, the passive situation, the quiet city, the sleeping people in their houses and mobile homes – who are then wrenched out of their calm by the glare of light from above. The separation of private and public is imaged in a way that underlines the almost violent and brutal disruption that occurs where the public encroaches on the private. These are images that recall satellite pictures, reconnaissance photographs, shot from police helicopters, painfully visualising the subject of omnipresent surveillance in their harsh black and white.

Annika von Hausswolff’s photographs of the last two years probe the unfathomable abyss opened up by enigmatically ambiguous situations. In the whodunnit colours of a lurid flashlight, she shows women in night-time surroundings, turned away, busy with something unknown that encroaches upon them from outside (exogenically) or inside (endogenically). Enigmatic and almost surreal interiors bear such titles as ”Everything is connected, he, he, he”; ”The petrified couple”; ”Now you see it, now you don’t”; ”The best stories are the ones never told” showing a woman sucking her thumb, a couple lying on one another, ”Mom and Dad” like dolls in the form of a cross, centering on the genitals but at the same time covering them up with almost old-fashioned ”doll-like” prudery. Dream-like, oppressive, sometimes even threatening situations, telling of a life that seems fluid to the point of flowing away.

Hans Hemmert is a sculptor and installation artist who has created a series of situations that can only be ”conserved” photographically. He fills interiors with a large latex balloon – a car in ”On the way”, his studio or his home in ”Saturday Afternoon at home in Neukölln” – and then he moves around inside briefly as long as the oxygen lasts. Outer skin becomes inner skin, interior becomes exterior, like an alien and artificial space. The images tell of the alienation of an environment, addressing the fragility manifested in such a stable ”home order”. The yellow balloon lies like a veil over familiar surfaces, materials and colours, alienating them, distancing them, robbing them of their power of significance. The result is artificially ”spacey” rooms.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s ”Streetworks” address the precariousness of individual existence. He moves in cities, often photographing crowds, but directing his use of the flash to draw one figure out of the crowd and freeze a movement. He decodes the ”formless” mass for a moment of photography, building up potential tension between the individual and the other, between the path of the one and the traffic of all others, between the rhythm of a person and the acceleration of the mass. This moment of focus emphasises the hybridity of man between social creature and loner. At the same time, it also addresses the hybrid of street photography. In his pictures it becomes clear how stage-like and ”staged” street photography is, and how far from supposed authenticity.

Jörg Sasse’s ”Computer-manipulated works” are often based on amateur photographs by friends showing situations that call into question the standpoint of the observer and the subject of observation. What is it we see there? asks the subject when the pictures appear so familiar as though we could see a landscape in front of us, house fronts, a moving and unfocused scene. What do we see? All the characteristics and patterns of order that confirm what we see are silenced, quietly and subtly put out of action. The perspectives evoked are visual traps, cul-de-sacs - but they are there nevertheless. The totally constructed, artificial pixel worlds before us insinuate the reproduction of reality, but they leave something out or add something until a sensation of floating is created. These are floating images that dissolve our sense of place, evoking new kinds of spaces in which time itself becomes almost timeless. These are constructed visual worlds with the power of fiction and suggested plot, of seemingly transcendental unfathomability.

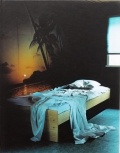

Isabell Heimerdinger, who studied in Stuttgart and has spent the past few years in Los Angeles, seems to have been infected by the proximity to Hollywood, for she treats the theme of the artificiality of film, the film set and the act of filming. Her series ”Working in Hollywood” shows film sets, and location work in which real situations are altered, or hybridised, by the use of light. In her ”Interiors”, by contrast, she takes a different approach. She processes details from films in which she removes the persons, the actors. What remains are interiors created for a filmic fiction – a constructed environment, the shell of a set. By removing the persons the film stills appear at first as documentations, medially alienated, of obscure status, oscillating between real reproduction and media construct. Yet, in time, the constructed, the intentional and the narrative take such a hold in these strange, empty, gloomy and oppressive spaces that we invariably come to expect a storyline or plot in the empty rooms. By processing neo-gothic films and, more recently, also Japanese films, she constructs medially exaggerated interiors that become enigmatic images of possible human action.

Needless to say, none of these positions provides a definite answer to the emergent questions, but they do offer images that give us an introduction, allowing us to consider these new models, and to experience them as model-like, in photographs that not only portray hybrids, but which themselves have been created, more or less, in a hybrid way.