Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits demand to be calmly looked into. In her works, our eyes — oriented, or even calibrated, to the extreme opposites of the gray, pale, cramped everyday world and the colorful, bold world of the media — are forced to view calm, apparently simple images, to pay attention to small changes, and to take in a chromaticity, which in its reduction is remarkably fine and simultaneously rich. Rineke Dijkstra sets up a minimal image in which “it” occurs, “it” shows itself. In a delicate combination of staging and coincidence, a person — a girl, a soldier, a young man — becomes a portrait, becomes a picture, presence, transforms into a visual present with temporal past.

In these settings — natural or built “landscapes” — we compare young bathers: for example, the shy adolescent gestures of a girl from Eastern Europe in her unfortunate imitation of received poses, the presentation of an oiled, at once bold and awkward young body. Or in the pictures of a girl we recognize how her entire body language abruptly changes once she can finally place her feet on the ground when she is sitting. The sweet, clumsy, and shy creature transforms immediately into a self-confident teenager staring sassily at the camera. Rineke Dijkstra often shows in her pictures how adolescents gradually gain contours, how their facial features, which appear almost as smooth as polished marble, begin to receive the first traces, the first signs of their own history.

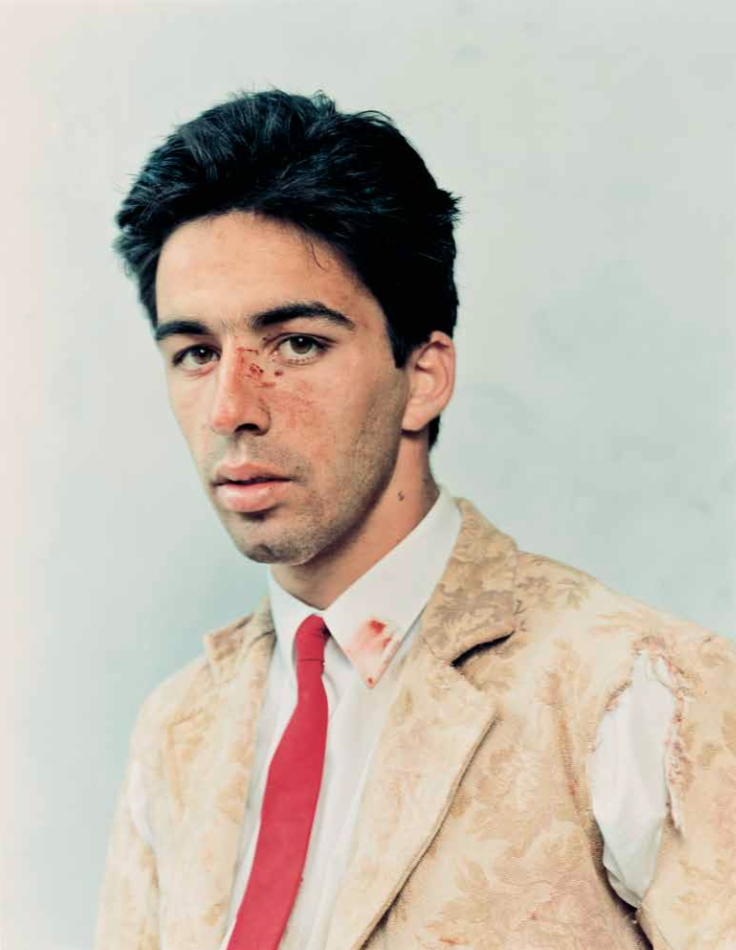

Three groups of photographs go beyond these minimal portrait situations. The pictures of young mothers, young toreros, and young Israeli soldiers in the Golan Heights contain a crucial excess: we look at the young people who have been photographed in the wake of a special, “violent” event; an event in which they took part, a change that they have submitted themselves to, an action for which they are now responsible.

Restricted to the head like photographic busts, the two close-cut portraits of the young woman Tia, taken directly after her having given birth and then five months later, depict recovery in a quiet way. The changes in her features are legible as a measure of the strength Tia gained within just under half a year. The impression of emaciation in the first picture gives way to a reinvigorated, radiant woman.

Taken in front of a light, pale grayish blue background, the toreros are also busts. They bear the traces of the struggle, the theatrical dance, and, like Tia, they show the signs of exhaustion. Their ties are out of place, jackets torn, and faces appear tired; their eyes are slightly murky, and smeared blood spots recall the fight. The expression — tired, pale, exhausted, or direct and cocky — is different from picture to picture, from face to face. The sensation seeps through the skin to the surface of the photograph as if through a semipermeable membrane in an osmotic process.

The Israeli soldiers, portrayed directly after their first target practice, appear more relaxed. It was only just a rehearsal, not yet a real battle. Appropriately, they assume poses that are much more calm, bemused, or “vigorous,” presenting themselves to the camera in full battle gear, with machine guns and camouflage. While one is still insecure, the second already appears more at ease, and the third poses as a proud soldier. In each case, the young face contrasts with the machinery the soldier carries, with the power of the weapon in his hand.

In 1766 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing composed the text “Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry.” The model for the text was the representation of the fight to the death of Laocoon and his sons in the sculpture by Agesander, Polydoros, and Athanadoros of Rhodes. The sculpture shows Laocoon and his sons battling against the snakes. From the sculpture, Lessing concludes how important it is to represent not the pinnacle, the extremity of the struggle, but rather the moment directly before that: “The master strove to attain the highest beauty possible under the given condition of physical pain. The demands of beauty could not be reconciled with the pain in all its disfiguring violence, so it had to be reduced. The scream had to be softened to a sigh, not because screaming betrays an ignoble soul, but because it distorts the features in a disgusting manner. Simply imagine Laocoön’s mouth forced wide open, and then judge! Imagine him screaming, and then look! [It was] a form which inspired pity because it possessed beauty and pain at the same time. . . .”*

It is remarkable that Rineke Dijkstra, who in some senses aims to create a classic portrait, chooses for her portraits neither this moment before, leading up to the climax, nor the highpoint of the fight itself; rather, she takes the moment immediately afterward, the moment of release, of exhaustion, after the will is spent. The person has lost the strength of action for the moment, and although “victorious,” is marked and wounded. She seeks this soft, tensionless state. The sitter opens up then, does not assume a strong, defensive pose against the almost automatic process of becoming image. The choice of the moment after the climax offers Dijkstra a field of fine, “involuntarily” given insights into human existence. She creates portraits that represent neither rituals of affirmation nor intentional or victorious poses. She rather creates portraits of experience that, in the age of garish poses and shrill cries, grasp a new form of quiet monumentality and existential beauty.

In spring 2010 the group of works presented here will be published in book form by Kodoji Press (Baden).

*Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, trans. Edward Allen McCormick (Baltimore, 1984), p. 17.