“No, we don’t have anything. The company has changed hands too often.” —“Glass plates? No we threw those away by the container in the sixties.” —“Original prints? As far as we know, the photographers always asked for their prints back.” — “No, we don’t have time to spend hours looking for photographs for you. And anyway these photos don’t fit our image anymore. Today we are a modern company.” —“No, the photography department has been dismantled along with the archive.” —“Yes, we have photos, but the company has split, and since then the archive has been wandering from place to place all packed up on pallets.” —“This photo? It must have been stolen at some point. Yes, it was reproduced in the book. You found a copy? We don’t have any more copies ourselves.” —“Yes, the first time you were here the photo was still intact.” —“Yes, I did see something like that once, in an envelope. Would you like to come by or should I send it to you? It’s now the end of June and then we have the holidays. Should we say early September?” —“Yes, we have a lot of photographs. Come at ten. Then I will invite you to lunch. You will need a full day to get a first impression.” —“Yes, I think we do really have interesting photo material.”

The potpourri of answers could go on and on. It recounts the arduous searching until a photograph was finally found, the disappointments of the disappearances of key images, and a few positive surprises. Especially when the first inquiry receives no response and the second is met with the negative answer that their archive is boring and unimportant, and then in the end one is surprised to find that the opposite is true. The Escher Wyss archive (today Sulzer-Escher Wyss) turned out to be an exceptional find, which sometimes contains an almost surreal parallel world to the officially cultivated image of Switzerland. Most of all, the quotes above (shortened and sharpened) show what little value the industrial photographs on the shelf were assigned, how little worth they had even to their owners. There may be two reasons for this. First, although industry was the motor of modern society, the history of industry is still a discipline of low status. No social laurels are to be earned through its pursuit. Second, factories are not places of contemplation. Their sole goal is productivity; the thinking and actions inherent to industry are conceived in terms of means-to-an-end and are focused on the present or the future. Photography was inevitably subordinated to this attitude. Photographs were requested, implemented, rejected, and forgotten. And if a company’s productivity begins to falter, cuts are made where possible. Also to the past, also to the company archive. No time for reminiscing, no money for sentimentality.

Company anniversaries are some of the rare exceptions. That is when they go back into the archive, send someone down to the basement to sort through the past, commission an external photographer to create an image of the present, and publish—usually in a small edition—an illustrated booklet commemorating a major anniversary, whether a young 25, a grand 125, or even 175 years. Company history often brings opportunities. These kinds of company publications often marked the starting point of our search; they were proof that photographs existed (or at least once did); they gave reason to be persistent, or determined even. They were indication that within a certain period the quality of a company’s photographs was outstanding. Company archives are usually not continuously well maintained. They are erratic, containing many good photographs for a while and later only junk—sometimes in such mixed up sequence that it seems as if no one noticed the difference in quality, as if a photo was just always a photo, apparently without noticeable impact on product sales.

The low status of the history of industry is mirrored in the condition of the photographs and the archives: photographs exposed to years of dust and dampness; glass plates, at least wrapped in paper but stacked together in such numbers that they still got scratched. Early color slides, testimonies of the 1950s and 1960s bearing countless fingerprints, which have chemically and fundamentally altered the basic colors, bright tones having dissipated into a uniform brown-pink (technically called magenta, which has also faded). Often there is not really anyone responsible for the archive. Or then there is someone, a retiree earning a little extra money, who has no knowledge of the company or how to handle photographic documents. Some of the exceptions include the archives of Landis & Gyr in Zug, Sulzer AG and SLM in Winterthur, and SIG and GF in Schaffhausen. Here photographs have been carefully preserved and are in part organized according to modern criteria.

It seems that in the industrial context photography was often categorized as inferior, as a mere technique. In the sometimes very opulent anniversary publications one notices how all contributors are named, even the illustrator who provided four to six illustrations. But there is never any mention of the person who took the thirty, fifty, or seventy photographs—with rare exceptions, such as Jakob Tuggener. The industrial photographers were the “proletarians of creation.” This is astounding, largely because photography seems to be the most appropriate medium for documenting industry, given that it itself is a product of technical and scientific progress, a mechanical-physical-chemical tool, a principle discovered during the period of industrialization and which provides a corresponding image to a sense of mastery and command of the world. But precisely this likeness, this principle relationship between the two, seems to in part degrade photography. Every new development tends to initially clad itself in the values of the preceding era, the same is apparently true of the industrial sector.

Archives as “Visual Territories “

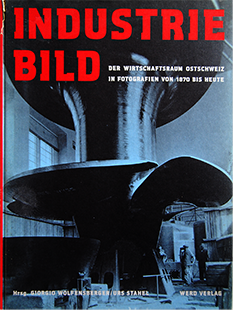

With the gradual disappearance of—what today we would call classical—industry arose an interest in industrial archaeology. As the factory halls fell empty, there emerged an awareness for the quality of the spaces that had been erected, the generous proportions of the factory complexes and the architecture; maybe the same thing will happen to the archives and the photographs in enough time for their richness and their historical value to be recognized. They are nothing less than part of our cultural heritage, the visual arsenal of one of the most productive periods, of the most powerful and forceful sides of Switzerland; a visual heritage that remained hidden for a long time.

Entering a well-stocked archive, one usually finds oneself in front of Ergo metal shelves where old original prints, glass plates, negatives, and albums are preserved. Albums as far as the eye can see, fat, squat, distorted tomes, into which the life of the factory has been glued, chronologically ordered, and numbered. Specially kept registers or reference books sometimes provide information about what is seen on the photographs. Only over the course of time is the date integrated into the numbering systems. Corresponding to the chronology of events at the company one can trace what took place simultaneously in various corners of the factory complex. What aspect of production had called for a photograph at that moment. The clear and simple organizational system of a chronology results in the opposite, a surprising, diverse, curious juxtaposition of images. Photos documenting machine parts, assembly halls, porous surfaces. Portraits of workers celebrating anniversaries of service, retirees, or directors are placed next to photos for a set of instructions, a brochure with instructions for preventing accidents, between them photos of the canteen, the workers housing, organized leisure time, and once and a while an areal shot of the factory complex. Allan Sekula, the American photographer and theorist described archives as “visual territories.” They are open terrain, in which workers are portrayed next to the stockholder, tools are placed next to the product, the product next to the people. Here the original use and significance of the image was first put to rest, but when taking the photograph out a second, third, or fourth time, a new significance is gained each time, depending on how the photograph is viewed. There is always the danger that the context is lost, that images in an archive are subject to abstraction, that the depicted appears in “abstracted equality” to the next. The historical document, freed from its original meaning, gradually becomes a purely aesthetic object, an image of the imposing power of industry.

“A source never speaks, it answers” is a quote in an unpublished master thesis by Marc Zollinger. Taking this a step further, one could say that a source never speaks, it is silent. It remains silent until questions are posed to it, until there is something someone wishes to know. This silence does not mean that we may view the photo archive as neutral, as something that has become unbiased historical material providing us with reliable information, as something that naturally lends itself to being viewed from any perspective. We ought not forget: The archives only hold the history of industry that has been photographed. The part not photographed is missing. They contain the part of industrial history photographed with a specific intent, a part permitted to assume visual form and take on meaning.

Then again, there is hardly any part of this history that was not archived. Everything that was photographed was done so with a clear mandate, and ultimately everything was filed and archived. The modern corporations that later grew out of the old industrial firms sometimes then did away with the archive, their own past—either for financial reasons or as a way of making a clean sweep with their old image. The self-perception of a company is mirrored in the archive. The industrial photograph is not so much a neutral document as a “concretization of social values,” as David Nye wrote in his book on General Electric. For companies this largely meant a display of innovation, productivity, efficiency, a demonstration of economic and technical potency and constant growth.

In the archive of the Bühler company in Uzwil for example there are reference books containing all the mills, dough presses, and printing equipment which Bühler sold throughout the world—each at its final destination. Through these photographic references Bühler creates an image of a company doing business throughout the globe—in short, a global company, based in Uzwil in St. Gallen but found in India as well as at the Cape of Good Hope and in Nebraska. Today these references offer the advantage of helping us find out about companies which have long ceased to exist and whose archives have disappeared along with the company. However, the Bühler archive is also interesting from a different perspective. Although it was common practice to have company photographers travel along with the machines, for example as Sulzer did in Europe or Georg Fischer did throughout the globe, Bühler sometimes commissioned photographers on site. The same machines photographed in different environments by different photographers offer prime research material for studying different visual cultures in an international context.

Back to the homeland. In the books and albums of the construction companies Hatt-Haller and Locher one finds depictions of a good portion of Eastern Switzerland. In the photographs from Hatt-Haller the places depicted were often under construction and are shown in various building phases, recorded by the head engineer as a kind of logbook. Locher generally tends to show only the final product, the bridge, the power plant, the smokestack, the factory hall—the construction built by human hand, completed, cleaned, and, before going into operation, also photographed like a monument in an objective and authoritative style by photographer H. Wolf-Bender.

One of the most comprehensive and interesting archives is that of the Sulzer Company, which includes an estimated 200,000 large format prints. Sulzer enjoyed a long boom, did business worldwide, and was considered the largest machine manufacturing consortium of Switzerland. This made Sulzer into a city within a city, into a relevant social structure on its own. This constellation is reflected in the archive. More than in almost any other company, here one finds, in addition to a wealth of proudly official images, photographs of life at the factory as a special form of large family, which extends even to the allotment gardens that surrounded Winterthur in surprising density.

What has been said thus far suggests that industry tends to present its history in a positive light in its archives. After all, the archives have not preserved photographs of the “other side” of the story, of the worker’s movement. However, since the context changes and shifts over the decades, this positive focus becomes more ambiguous. In retrospect the images can be read counter to their original intent, if so desired. More crucial than the positive tone of self-representation is the fact that the companies are the owners of their archive. This means that they may do what they please with the images, edit or destroy them—and given the sometimes incredible wealth of visual material with relevance beyond the company context, this causes irreparable damage.

The Daily Routine of the Industrial Photographer

Before we examine the work of the industrial photographer, an important differentiation must be made. There are two types of industrial photographers. First, there is the factory photographer, who is employed by the company and carries out desired jobs on a daily basis. Second, there is the freelance industrial photographer, who is commissioned for special occasions. The factory photographer works anonymously, is a salaried employee, and may not take any photographs home with him, even the ones that land in the bin. The company signed the photographs with its name and a number. It is only possible to learn the name of the factory photographer through the personnel department, if the documents go back that far. In contrast, the freelance industrial photographer who comes to the factory for a commission, a special occasion, retains certain rights. For example, he can demand that his photographs only be published with his name on them. Many of the early Sulzer photographs are stamped with the name “Linck,” which means that they were taken by Johann Linck and his son Hermann Linck. Around 1906 this name disappears and is not replaced by another, not even by Johann Fülscher, for example, who is mentioned as follows, “...in association with the advertising that was generally introduced for our products at the time, he was the first to introduce photography and developed the retouching of images for advertising purposes.” The disappearance of photographer names is an indication that Johann Fülscher established the internal photography department at this time and probably served as the company’s first photographer.

Further on we will examine how the photographs of internal company photographers differed from those of freelance industrial photographers. At this point, the important fact is that one generally does not know the names of the company photographers, while the names of their famous colleagues, who seldom worked exclusively as industrial photographers, are familiar: Johann Linck, Hermann Linck, Carl Koch, Rudolf Zinggeler, Paul Senn, Jakob Tuggener, Hans Finsler, Theo Frey, Ernst Heiniger, René Friebel, Michael Wolgensinger, René Groebli, Louis Beringer, Hans Baumgartner, Hans Peter Klauser, Herbert Maeder, Roland Schneider, Werner Hauser, H. R. Bramaz... Also important, the quantity of photographs is inversely proportional to the photographer’s level of prominence. The majority of photographs was taken internally by anonymous company photographers; most of the photographs presented to the public beyond the factory walls were taken by photographers with a “name.”

Like all other workers, the company photographer must adhere to the discipline of the factory. This means starting on time, arriving a few minutes beforehand. His assignments are delivered in written form: Report to Foreman Müller in the pattern department at 9:00 am. Requested, for example, are five photographs of a pump casing in black and white, one in color, all in the routine format of 13 x 18 cm. In order to walk across the factory complex, he must put on a work coat and helmet. If the photograph is to be taken at the factory, then it suffices to load all his materials—professional camera, tripod, four to five lamps—on a wagon. If the shoot takes place outside the factory, then the company limousine must be ordered. If one of the large halls needs to be illuminated, this constitutes a major endeavor lasting the entire day. In this case, numerous 5,000 to 10,000 watt spotlights are needed in order to balance out backlight or compensate for the combination of the dark floor and light ceiling. “The part is finished. The truck is waiting to transport it. A ‘quick’ photograph still has to be taken. The photographer would like to be lifted into the right position by a forklift. No forklift far and wide. There is hectic activity on the factory floor. All forklifts are being used, but the photographer would like to take a good picture. The object must be cleaned. The truck is waiting. There are objects standing around which are not allowed to be in the picture...” A typical situation described by Max Graf, a former company photographer for Georg-Fischer, to his younger colleague Theo Stalder.

The photographer has to be able to assert himself on the factory floor while still adhering to the strict hierarchy of the operation. Although he has been given a job to do, no one has time for him; production must keep rolling. At Sulzer photo apprentices were given foreman helmets, so that the workers would listen to them and the crane would bring the spotlights into correct position. Lighting and photographing a cogwheel in front of a white background in the corner of the factory hall demands calm and concentrated work. In contrast, it is a tricky and fast-moving job to ensure that one does not miss the high point of industry and industrial photography, a major pour, the culmination of a long period of preparation. This must be planned long in advance. The actual casting, and above all the photographically impressive spray of sparks (the sunset of industrial photography) only lasts half or maybe one or one-and-a-half minutes. Within this timeframe at least one of the photographs—in the unwieldy 13 x 18 format—must be a success. Often one photograph, one assignment in its different variations, takes an entire day. In the evening the factory photographer returns and gives the films to the laboratory workers for development.

This description neither quite fits the present nor is it valid for an all too distant past. In the beginning industrial photographers were ingenious tinkerers, because there were special demands in terms of tonality, light distribution, and focus. A number of them still coated the glass plates themselves; all knew how to tone down or accentuate parts of the image and still personally retouched the negative, for example with red aniline or neococcin dye. Now, color is almost exclusively the order of the day, powerful flash units are used for illumination, and super wide lenses can capture everything at once. The description corresponds to what Giorgio Wolfensberger experienced at Sulzer in the 1960s, when he did his apprenticeship as an industrial photographer—at the end of an extended epoch of successful industrial photography, at the beginning of the transformation, and perhaps demise, of the discipline.

At the large metal, machine, and electro plants of BBC, Escher Wyss, Maag, Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon, Sulzer, Rieter, Bühler, Georg Fischer, Alussuisse, SIG, Siemens-Albis, and Landis & Gyr the demand for photographs was at one point so great that the photography departments employed up to ten or twenty people—photographers, apprentices, lab workers—and even the process of taking photographs was performed according to a division of labor. The reason for this quantity of photographs stemmed from the size of the companies, the constant change in the work-pieces, the need for illustrative photographs for export and symbolic photographs for the representation of the company. In other sectors, especially in the textile industry, many companies did not have their own photographers. In a spinning mill the production process, type of machinery, and even the product look similar or even just the same over the years. In addition, working conditions were often worse than in the machine industry. Enough reasons to only have a few photographs in the archive. Whereas tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of photographs are stored in the major companies of the machine industry, one only finds individual photographs in the textile industry, if at all. One is then happy that a photographer such as Theo Frey came from the outside and photographed the small operations of Eastern Switzerland with almost meticulous care.

Objectivity as Dogma

The description of daily routine does not explain all the things the industrial photographer had to photograph and what he had to pay attention to. At one point in time, training as a photographer in a large industrial company was one of the most interesting and comprehensive apprenticeships possible. The industrial photographer had to make portraits when a worker joined or left the firm, when he retired. He was required to document traces of wear and casting flaws, in other words to test material photographically. He needed to be able to light and photograph a simple small object so perfectly, that one could identify what material it was made from and how it was fashioned. He had to be able to achieve the same thing on a large scale, when photographing a cogwheel 10 to 14 meters in diameter, a gas turbine, or a transformer. He became an architectural photograph when required to photograph the giant factory halls from the inside and without. He created small series of documentary photos featuring tours of the plant and company outings. Always anonymous, always as the company photographer, whether working in micro, macro, or normal dimensions, always with a professional camera, early on with a 18 x 24 cm format and later with 13 x 18 cm, always also with a tripod, which demanded the calm and concentration reminiscent of a painter and his easel. The industrial photographer recorded, tested material, practiced, rehearsed procedures, documented incoming people and goods, assisted the patent department, provided for internal communication in company memoranda and served the external mediation of the company in its so-called “Propaganda”-brochures; he familiarized the viewer with new and old and represented the achievements of the company, its products, as objects that seem to have fallen from heaven, in front of a white backdrop, detached from the context of production.

Regardless what he photographed, the industrial photographer had to adhere to very precise rules, perhaps more so than in any other field of photography. The image had to be fine-grained, contain a balance of tone throughout, be in high focus within the image plane, and all objects had to be portrayed with as little distortion as possible! These four criteria became the international credo of industrial photographers. In order to achieve this, he had precise knowledge of all different kinds of film, employed spots, mirrors, and white paper to present the work-pieces in the right light, and by using the Scheimpflug principle the focal plane was adjusted so that key elements were in focus. If highlights interfered with the photograph—there were flashes of light everywhere in machine halls—metal parts were dulled in various ways. When developing the film, during this copying process, elements were evened out, toned down, or accentuated if necessary; later the negative was retouched with a scraper or a very soft pencil (“In order to retouch a negative with a pencil, the surface must be rubbed with mattolein, a solution of kauri resin in turpentine oil.”)—until the desired brilliance, density, and distribution of light and dark is achieved. If a machine needed to be set apart from the rest of the image, a masking paint of red tempera was applied directly to the positive—initially with a brush and later with an airbrush—so that insignificant parts appeared diffuse whereas the most important appeared crystal clear and immediate.

These and a series of other measures were taken in order to achieve a well-rendered, sharp, undistorted, and materially accurate representation. This actually poses a paradox: in order to achieve the desired objectivity, all the tricks of the photographic technique were employed, including almost painterly methods. In order to generate this certain neutrality in the representation of the object, every trick in the book was used to manipulate the photograph. David Nye writes, “The photo is doctored, is processed.” These are not simple, documentary depictions but carefully constructed images, which characterized industrial photography worldwide, with minor differences characteristic of various regions and periods. Whether an object is photographed in front of a white background in a kind of magical thing-realism, whether a factory hall is photographed with gleaming machines which have been set in place for the shoot along with the workers, or whether we, more obviously, find ourselves drawn into a photo of a deep receding space where a row of workers are welding work-pieces as if they were actors in the play “Autogenic Welding in Three-quarter Time”—everything is always staged, arranged, and after an extended period of preparation then also photographed. The dark surroundings and the low sensitivity of the film technically did not allow all the men to be in focus. So they had to get into position, begin welding, hold their breath at the count of three and not move at all for two, three, or four minutes. Only in this way was it possible to realize this photograph. As a rule, one was not supposed to sense the staging in the final photo, which was instead supposed to radiate an appearance of objectivity. In the example described above, one immediately senses—which is unusual—that this is not a realistic depiction. The workers have been too consciously composed in a group arrangement to create a kind of restrained symbolic image on the theme of coordinated and efficient work.

In talking with industrial photographers, from both older and younger generations, one experiences something odd. A photographer immediately launches into a story and tells how complicated it had been to take a certain photograph, how many flashes he had used, “yes, sixty, and then I still had to have the wide angle lens reconfigured.” It is as if he himself were a mechanic, an image engineer instead of an image maker. There is no discussion about the aesthetics of a photograph, the possible meanings it has assumed. The photo is not an aesthetic product but an event, a production, a staging. With this attitude the industrial photographer becomes a director, and the photograph an “industrial still,” a still life set apart from the production process, much like a film still of a Hollywood film.

Practically speaking, the aim is always objectivity, something deeply rooted in the photographer’s self-understanding. However, one does notice how this objectivity loses its apparent neutrality and becomes a kind of corporate identity for all of industry. This is the picture that industry, Swiss industry, wishes to project. It is perfectly aligned with industrial notions of the technical, the mechanical, precision, and cleanliness. The objectivity of a photograph represents a sign of quality, much like the crossbow label signifying “Made in Switzerland.” Objectivity avoids the darkness, the soot of the foundry—the images generally seem lighter than the factory hall truly was. Objectivity eliminates dirtiness and sweat and thereby also an element of the worker’s manual work. Machines do not sweat. Objectivity avoids all moments of expressiveness; production processes are organized and efficient. There is no sense of hectic; emotions are only allowed at the end of the day.

To a certain extent objectivity correlates with a cleansing of industry. This is underscored by the following technical necessity: A room for of spinning machines could not be photographed on a working day, when the machines were running full tilt. The vibrations would be so strong that the photograph would be blurred. So the photograph was taken on a Sunday, without people, without any dynamic. Reinhard Matz discussed these issues in his book on industrial photography from the Ruhr region through views of factories and the question as to whether smoke should be coming out of the smokestack, and if so, how much. Even at the turn of the last century, too much smoke made it look like pollution, but no smoke at all made it seem as if the factory was at a standstill. Therefore, for the “documentary” photograph, which later decorated the company’s letterhead, a gentle gust of smoke was shown coming out of the smokestack. Such subtleties were seldom employed in Eastern Switzerland, simply because the amount of truly soot-producing industry—coal and iron smelting—was relatively small in comparison to the Ruhr area. Allan Sekula used the phrase “instrumental realism,” and Cesare Colombo describes the promotional nature of scientific looking photography. The objectivity of the photograph void of any personal signature was appropriate to the intended purpose and the mechanical object depicted. An unusual coalescence of motif, medium, and intent.

As a rule, one does not think of industrial photography when talking about the “straight photography” that developed in association with Alfred Steglitz in the US or about the New Objectivity that emerged in Germany. Counter to the way photographic history has been written up until now, David Nye makes the claim that industrial photography influenced “normal“ or artistic photography, because the photographs of General Electric, for example, have been published many million times more than any artistic photograph. Much speaks for this view, even if it is not easy to prove. Certain is that the photography of New Objectivity—this consciously emotionless positivism and materialism, which was directed against the romantic and symbolical overload if the 19th century, against the bourgeois pictorial imagery and against the expressive—was clearly influenced by new forms of production and construction, as was industrial photography.

The visual imagery of external industrial photographers

“For my many reports on factories, which took me all across the Swiss industrial landscape, my job was usually to document production processes while remaining aware that I was there by right of hospitality and that I was not supposed to make my assigned escort nervous. I was to avoid asking company workers awkward questions about their pay and leisure time, remarking on poor hygienic conditions, or poking my nose into places that were taboo. Inevitably, socially critical questions arose in my mind, but I was only allowed to incorporate these into my texts in small doses if I wanted to avoid trouble. But this did not mean that I had to remain impersonal and neutral. Photography was able to express many things at the same time, not only what was on the surface but also subtleties, surrounding circumstances, the human climate. Again and again I noticed that a sense of confidence and professional pride came through where trained specialists were at work. However, where unskilled workers clocked in their hours to earn a living, they usually did so with a fatalistic sense of resignation.”

In Theo Frey’s retrospective description of his time as an industrial photographer in the 1940s one notices an emphasis on people and their behavior patterns. Are the photographs taken by freelance photographers, commissioned by the company, a magazine, or initiated by the photographer himself, noticeably different? There is this escort tagging along. He is what one could call the “company guy,” always at the photographer’s side. He opens doors, makes introductions, makes things possible on the one hand, but monitors and hinders on the other. Does the freelance photographer adapt to these circumstances and adhere to these rules or does he create alternative pictorial worlds? Let us take a look at the imagery of some of these photographers.

Johann and Hermann Linck, father and son, founders of a photographic dynasty in Winterthur, are outstanding photographers from the late 19th century and early 20th century. They are among the first Swiss photographers to have practiced industrial photography. Neither was adverse to bourgeois representations—the father was a little more painterly in tonality, the son somewhat more austere. One could cautiously describe their position in industrial photography as follows: Johann Linck is a photographer of the 19th century. Without lapsing into a cult of the painterly and picturesque, he seems to understand photography as a form of looking at landscape and comprehends the view of the landscape as imbued with a gentle feeling of being uplifted, of understanding. His photographs of industry, usually void of people, are rich in tone and have the appearance of slightly romanticizing, slightly symbolizing photographic paintings—including his magnificent photograph of the forge at Sulzer. His son Hermann’s work seems somewhat cooler. His wonderful series on the Haldengut brewery is also composed like a sequence of landscapes, but they are precisely plotted, have sharper contours, and are more graphic and objective than his father’s photographs. Both work with spacious, static image fields with barely any dramatic accents, abbreviations, or abstractions. People appear only seldom. From today’s perspective, a certain academic quality is inherent to both, but this serves an uncontested quality of precision in a period dominated by picturesque and painterly romanticism.

Hans Finsler—who came to Zurich in 1932 from Burg Giebichstein, a design school in Halle, and not only founded the photography department at the School of Design but also introduced New Objectivity to the Swiss photographic community—produced few important works of his own after coming to Switzerland. These primarily included his photographs of the Heberlein textile factory in Wattwil and his work on typography, lithography, typesetting, and printing for the Fretz Publishing Company in Zurich. In contrast to the open industrial landscapes photographed at a distance by the Lincks, Finsler obviously worked up close, applying varying degrees of abstraction and focus to what he considered important. The irrelevant is abstracted in the composition; the image concentrates on the essential: the clarity and light-infused quality of the architecture, the clarity and precision of production processes, the soft, flowing quality of the fabric in contrast to the rectangular, hard forms of the architecture. His work on Heberlein, whose owners were his friends, is an erratically outstanding exception to the kinds of photographs one usually finds in the textile industry. These images by no means constitute a journalistic essay but instead an intimate drama in which intonations of New Objectivity play out across various forms and materials. And this New Objectivity is stirred by something more, something deeply metaphorical that wishes to assert itself through this positivism with a profound, orphic quality.

With this Finsler founded a tradition. Although sharing the spirit of the Zurich Concrete School, the Swiss New Objective photography differed largely in terms of quantity. The Zurich School of Concrete Artists remained one of many strains of expression as a very prominent but not a solitary movement. However, in the period during and after Finsler objectivity persisted to an usual extent—with adherents such as Hugo P. Herdeg, E.A. Heiniger, Werner Bischof (his early work), René Friebel, Michael Wolgensinger, and many others. Over time, the initially revolutionary pictorial language and outlook of New Objectivity became a kind of Biedermeier of the 20th century: the precise and clean depiction of the thing at hand, limiting the image to what is there and accentuating it, seemingly without questioning it. This kind of photography represented a universal form of expression in Switzerland from 1930 to 1970 and to a certain extent remains so today. It is not a contrasting position to factory photography; it has the same quality of material positivism but is less restricted in purpose. People do not play a major role. A world of forms predominates—of materials, processes, things. Photography as typography. Professional Sinar camera photography. Always exact. But when the exceptional talent of someone like Finsler is lacking—his ability to transcend the mundane “thingness” of objectivity—then this photography seems cool and sometimes even a little uninspired and boring. Photo 49, the special photography edition of the magazine Publicité et Arts Graphiques that came out in 1949, is an expression of this ambivalence. On the one hand, it shows the kind of Swiss photography described above as being of outstanding formal and artistic quality, and yet on the other, it sets the world and reality of Switzerland in the 1940s apart, as if it were all a theoretical, harmless game. There are exceptions from factory photography—which confirm the rule. These include the photos of the seemingly monumental turbines at Escher Wyss, or in the work of Gottfried Gloor, the company photographer of the cogwheel producer Maag Zahnräder, there are photographs, which overstep the rule of moderation.

The visual imagery of Hans Staub, Paul Senn, Jakob Tuggener, Theo Frey, and Roland Schneider represents a contrasting position. Incidentally, all of these photographers were largely neglected by Photo 49, although they belonged to the generation showcased in the magazine, with the exception of Roland Schneider. In all of their works people play a fundamental role in the photographs. The focus is on human activity and existence, on the relationship between man and machine, between the individual and working processes. Let us look at the work of three of these photographers. The special quality of Theo Frey’s work is the quietude of his images and the closeness of his camera to laborers. One senses a great respect for all working people, regardless of their position in life. Frey took photographs in many small textile factories. It almost seems as if his motifs and his photographs exist in symbiosis—concentrated, calm, modest, and a bit humble. In contrast, Jakob Tuggener photographed in the major companies of the machine industry during the 1930s and 1940s, and his images convey this industry with an unparalleled sense of force and heroism. He also aims his camera at workers from close proximity. He is standing among them. However, the image is not dominated by an aura of respect but by a will to create, to form, to forge an image. Tuggener uses people to create pictures of humanity and the world that take on a significance above and beyond the concrete situation. He must have sometimes given stage directions to create such determined, stringent, and incisive groupings of people. These elements contribute to the unmistakable, incomparable strength of his photographs, as in his almost sculpturally clear and precise “borrowing” of scenes in the factory.

The work of Roland Schneider and his partner Franz Gloor characterized the 1960s and 1970s with their grainy, raw black and white photographs addressing the relationship between people and their machines, life, the hierarchies on the factory floor, and the relationship between men and women at the workplace. Schneider was undoubtedly highly influenced by photographers Hans Stabu, Paul Senn, and Jakob Tuggener. However, his photographs usually seem more dry, more direct; they are less processed than simply snapped, realized in a quick and forceful shot. They therefore seem less metaphorical than some of the photographs of his predecessors, and this gives the viewer a feeling of normality. The images deal with work, with people who work, in very specific hierarchical situations—something that needs to be shown.

These three photographers (it needs to be mentioned that there were practically no female industrial photographers, the only known nme being Gretel Kusch, who worked as a company photographer for Sulzer) had one thing in common with other freelance photographers: they hardly ever used professional format cameras but worked in the 6 x 6 medium format or even 35 mm film. This provided them with greater mobility and immediacy and a higher degree of informality. However, this presented greater problems in terms of the depth of focus. The entire photograph is not sharp, and instead focus has to be used selectively. These images do not represent the reality of the factory in the detached precision and objectivity otherwise typical of the company. They do not reflect an effort to achieve a balance of tones but slip into blacks here and there, show contrasts, are intended as strong, immediate images of people. As a result, this is not the type of photography that a company could use in the previously described contexts of documentation and promotion. Instead it was used for different communication purposes, to convey the message within and without that the company was a people friendly workplace with a human touch.

This is a form of photography that almost became the counter-image of factory photography, even if some examples are found in company archives. The industrial photography previously described almost entirely ignored the person as an individual; people come into play when needed for a demonstration of scale—machine this big, person this small—when accidents and accident prevention are topical, and when it is necessary to establish a relationship to something or make it more comprehensible. In the industrial photography of the 19th century it was practically impossible to photograph people in the dark factory halls. At the time, the photographic medium’s lack of light sensitivity—easily requiring 10-minute exposure times—precluded a focused depiction of people. When this became possible around the turn of the century, industries had transformed into production facilities to such an extent that the individual identity of the worker increasingly lost significance. People are shown as parts of the machine.

Only in the 1970s and 1980s, when the concept of successful image and product marketing began to change, when the machine industry began to shift the focus from the product to the market, and finally when machine installations began to take on an unprecedented level of abstraction and incomprehensibility, people were then used to communicate a message. The industrial photographer Theo Stalder writes: “The machines and facilities that I have to photograph are fully automatic. How does this fit the requirement that the photographs ‘should prioritize people’?…So people are still placed next to operating controls which are actually only designed for emergencies…I am increasingly commissioned to do pure ‘people shots’, in other words photographs of faces and people without any direct relationship to the objects.”

One kind of photography does not fit any of the foregoing descriptions, the photographs from the food industry. People, women were shown in this context in great numbers, from the very start. The images consist practically only of female workers, standing rank and file or sitting while preparing vegetables or filling bottles. But the women workers are shown as a unit, as production machinery in a sector whose production processes were automatized later on. In the photographs the women appear like pietàs of the industrial age. Bending down to perform the work of production, they seem to assume a pose of humility.

Industrial photography today

It is astounding that neither the factory photography of embedded company photographers nor the industrial photography of freelance photographers (later also women photographers) seems to be marked by major developments. Is this due to the static nature of the circumstances or the commissions? One is tempted to divide the history of industrial photography in Eastern Switzerland into three separate epochs: 1870 to 1920/30, 1930 to 1970, and 1970 to today. Johann and Hermann Linck are the primary representatives of the initial period with their static, airy photographs of industrial “landscapes.” The subdivision of the second period into three elements—the objectivity of company photographers, the freelance photographers, and the “people” photographers—has already been described in detail. The developments spanning the entire period from 1870 to 1970 primarily seem to be dependent on the photographic medium: faster, more sensitive films, professional cameras with easier handling. A great, almost unbelievable leap is made starting in the 1960s and 1970s. At first color was introduced into factory photography, and today such photographs are practically all in color. Then there was the problem of the loss of a graspable visual element in industrial production. Finally, factory photography transitioned into PR photography, as described by Theo Stalder, in which the photographs have nothing more to do with the product. And finally, the photography departments were dissolved, because companies were cutting costs and every department had to function as its own profit center.

A look at the work of Roland Schneider helps exemplify one of the core problems of industrial photography today. Photography always relies on the visible, the concrete, what presents itself to the eye. One of its central functions is to make its subject matter visible and thus also knowable. When Roland Schneider began to concentrate on industrial photography in the 1960s, this Aristotelian principle was still ensured: a foundry still looked like a foundry, obvious, a turbine looked like a turbine, a planing machine like a planing machine. The degree of abstraction that existed at the time was surmountable photographically. And there were people in the factories, many male and female workers. Meanwhile the factory halls have emptied, high technology has replaced the human hand, and the machines have been reduced to light grey boxes which do not reveal anything about their insides, or to endless production lines that can be described well with aptly chosen words, and not so well with a photograph. Schneider insisted on the clarity of the visual, on industry as a place of the person and the machine, on grainy black and white documentation as an expression of the life of industry until it was essentially no longer possible, because there was nothing more to see except emptiness and coolness, except sterility. Today Schneider and his partner Franz Gloor cannot complain about lack of work, but in the bright colored advertising world of industry they have become dinosaurs.

Industrial photography has changed dramatically over the past twenty years. Where it has not managed to make the big jump from objective photography to clever advertising or PR photography, it appears disoriented and has become a banality of flashing bright colors and a desperate attempt to capture everything with a super wide lens. Perhaps this is a reflection of the diffuse intentions of an industry affected by major structural transformations. In the context of these changes the works of Winterthur photographer Werner Hauser seem pleasantly refreshing. His color photographs follow the developments and demands of an industry in transition. Sometimes he attempts to make hidden functions visible in an almost playful manner, but always somehow resulting in a photograph that rightly demands our attention. For the time being, his work represents a last positive surprise in a photographic discipline, which, thanks to dogmas and company ideology, has produced a very unique kind of photography. However, today such photography is usually only characterized by painful mediocrity.