Although photography can capture a piece of reality attractively and in such a way that it remains close to that reality, a way that can, with precision, reduce to two dimensions the three-dimensional world along with all its richness of detail, it nevertheless conversely appears to fix our gaze, to guide and direct it, thereby intensifying it, making it exclusionary. Over the course of the history of this medium, our field of vision has been so uncompromisingly entranced by the concept of the motif that we – starved of possible visual knowledge, on the look out for visual nutrition – have rarely directed our gaze beyond the edge of the picture. We have installed in ourselves a kind of optically fixed tunnel vision: through technologisation and automation that vision improved its views, insights, re-views as the decades rolled on and it mastered the rules of the game within the image, within the oblong angles of the frame with ever greater virtuosity; nevertheless – overcome by sheer curiosity, joy and love for the motif, coupled with busyness and a business sense – it hardly ever looked left and right, up or down beyond the boundaries of the square, never turned around and wondered about the extent to which the photographic image is dependent on the technological development of the camera, of the lenses, and of the carrier material for the image, or who might have made a photograph under what sort of social, political, economic, or media-specific circumstances. And yet these are conditions that usually heavily influence the image itself, the photograph, and its possible meanings.

It wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s that a kind of paradigm shift began to take place in viewing and understanding photographs. Gradually, the mono–ocular fixation was replaced by a systematic, contextualising way of viewing the medium of photography: the viewer, the apparent reality, the camera, the image, the carrier medium of the image, the epistemic interest, the commission context, the manner of use, the contemporary context – in other words, as much as possible of the entire range of media contexts is drawn into the meaning of an image. We frequently use the term linguistic turn to describe this change. With that is meant the new semiotic, media-critical and ideology-critical view of photography as a multi-perspectival, coded system, as a kind of visual language, as a complex image system that reflects reality on the one hand, but also generates reality on the other.

The American curator Douglas Fogle called this the rift that opened up in the 1960s: the “decisive moment”, as Henri Cartier-Bresson formulated it, was an important idea for many right up to the 1970s and 1980s, more specifically for the group of individuals who represented a modernist view of the aesthetic autonomy of the medium, i.e. those who viewed and discussed photography exclusively as taking place within the closed rectangle and considered this to be its field of creativity and truth, rather than in fact a complex, multi-perspectival, and coded system. This is a view that is ultimately rooted in the idea that photography is a panel image: “This rift between, on the one hand, the modernistic aesthetic translation of an authentic immediacy through capturing a photographic essence, with its own limits and possibilities and, on the other hand, the conceptual construction of a staged event that uses photography as a means to an end, provides an absolutely clear formulation of the distance between the two worlds, between the world of art photography and the world of art, which, in the 1960s (...), increasingly made use of the photographic medium.” So opened Douglas Fogle in his 2004 text “The Last Picture Show”.

This break not just with art modernism, but also with photographic modernism – that is to say, the first steps into post-modernism, the transition from implementing means of production to implementing means of reproduction (as, for example, in Warhol and Rauschenberg’s screen prints) – seemed to be necessary in order to generate a greater awareness of photography as a complex, multifaceted image machine. Since then, understanding of photography, the unity and absolute nature of the image has been fractured and fragmented into the viewer and the image, furthermore into the image and the reality, the image as a bearer of a message, as signifier, and the image as message, as content, as signified. Embodied in this model is the concept of the image as part of a network, as a sign that is now no longer entirely fixed, that changes continually through the projections of the viewer, through its many contexts, and that ‘shades’ and ‘overshadows’, ‘displays’ and ‘overlays’ reality – i.e. influences and changes our perception of reality.

Thomas Ruff’s attitude and developmental path is an excellent example for this. He began his work over thirty years ago with images of interiors that suggested contemporary documentary work. Seen with precision, carefully, indeed almost strictly framed, it is as if he wants to reduce the variety of reality to a morphologically small, readable, and comprehensible unit. Yet the effect is documentary, just like the large, coloured portraits, which, in their uniformity, in their cool, almost operational stringency, are reminiscent of the official, administrative photographs with which our entry into a company is recorded for the administrative departments. Or else they are reminiscent of the end of a symbolic being, representing the entry of each individual into the presence of a banal, pragmatic existence.

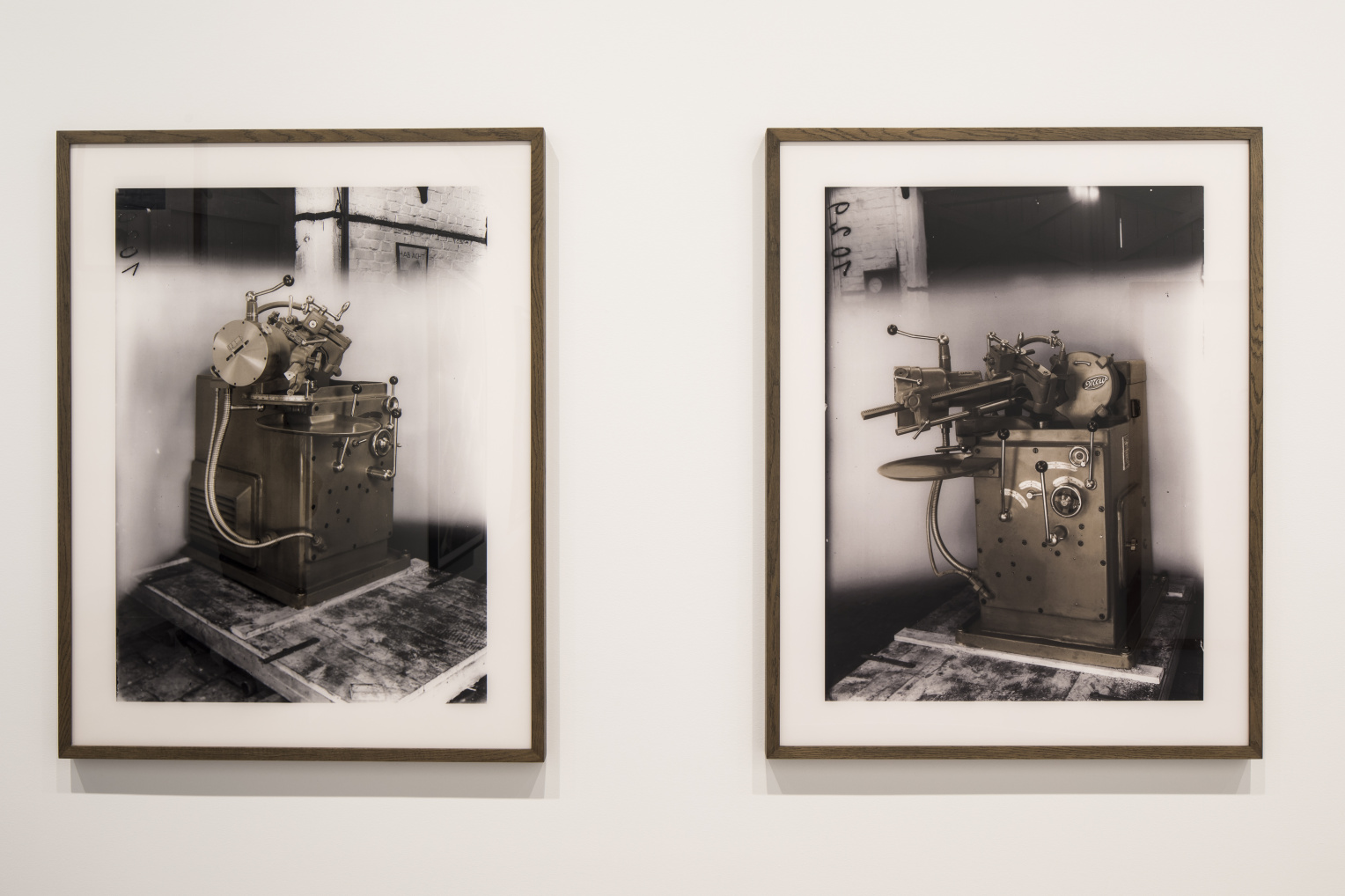

By contrast, the series “Nights” and “Other Portraits” are an irritation to the conventional notion of documentary photography from the first. In both work groups, the medium – the camera – began to play an altering, transferring, a visibly dominant role. In the series “Nights”, the low-light-level camera used in the military changes black, opaque night into a foggy, bleak scenario, into the theatrical and simultaneously frighteningly empty scenery of a green-tinged film noir. The “Minolta-Montage-Unit 401 P” special device used in “Other Portraits”, on the other hand, melds three portraits into a single portrait, pours three different pieces of image information into one mould, shapes three similar portraits taken from different perspectives into a single new portrait. Fiction or elevated, sharpened reality? This image mixer was implemented by the Düsseldorf State Office of Criminal Investigation in the 1970s to create phantom images as part of a “mobile strike force for visual identification”. What helped the police in the identification of potential offenders is, under Thomas Ruff’s hands, turned to the interrogation and irritation of our notions of ourselves, of complete, fixed, immutable identity.

These series and those that followed flash up aspects of the artist, progressively show the outline of an artist as a researcher, as an image demiurge, who sees the camera as more than an optical mechanical recording device, and instead as a powerful image machine, a complex “mill”, through which – depending on the motivations, the criteria, the selected recording system – he can transform the elements of reality into a new visual dimension. As if on a piano, Ruff continually plays on the classical genre of photography, creates portraits, nocturnal urban scenes, landscapes, transforms images of the sky into images of the stars, snapshots borrowed from press clippings, uses jpg documents to depict idylls and catastrophes, photograms created in a virtual dark room – he continually swings playfully between his status as a hunter and a collector, photographer and archivist, between generator and collector of raw data in order finally to pour out all the data into large format panels, which he then frames to be hung as remarkable, attractive, extraordinary settings on the wall.

Michael Stoeber uses the terms “body machines”, “machine bodies”, “machines of desire”, “computer (machines)” and “sex machines” to define the relationship between humans and machines, which he applies to Thomas Ruff’s art to describe it as a large machine that produces images and thoughts (Michael Stoeber, in: Thomas Ruff, “Machines / Maschinen”, Hatje Cantz 2003). Ruff is a processor of images who incorporates and transforms the found, collected, or generated raw materials of a multi-layered reality and hangs them as large image surfaces in rooms – hybrids of “dreams and nightmares, reality and illusion, facts and secrets” – or, as in the photograms, generates entirely new, completely virtual, and simulated images.

Scanning machine, collection machine, machine of the gaze and desire: the camera, photographing, making photographic fall upon reality, devour it and finally spit it out as a new substance. Jean Baudrillard described the cost of this: “The intensity of the image was precisely equivalent to its rejection of the real, its invention of another scene. To make an image out of an object means gradually removing all its dimensions: its weight, spatiality, scent, depth, time, continuity, and of course its sense. Only at the cost of this de-incarnation does the image gain its force of fascination.” (Jean Baudrillard, Photographies 1985-1998, Hatje Cantz 2000)

We can follow this most obviously in Thomas Ruff’s machine images, in the found industrial images that Ruff, with just a few alterations, makes his own and transforms. Here, we follow the action, the aims, the skill of the industrial photographer setting the scene for a small tool or a large, sometimes gigantic machine. The machines are cleaned, paint is applied to the edges and corners for highlights, they are sectioned off from the rest of the factory hall with a white cloth as a backdrop, and then photographed with a large view camera, a “room”, “la chambre”, as the French say. Once the film has been developed, the images are retouched, masked, and recopied, until the machine appears in the best light possible in front of a white background, until it is only an image, a machine model of the industrial age, saleable and usable. Thomas Ruff illustrates this transformation in many of his machine images. Only at the cost of this de-incarnation does a perfect object image emerge. The exciting thing about this series by Ruff is that we are able to follow the various stages of this transformation in the different images. Right through to the final image, the machine icon, the cog icon, the screw icon. Here the machine world is combined with the image machine to create a new third dimension.

Finally, in his “jpgs”, through images of skyscrapers, rocket launches, and atomic explosions we experience what humanity with all its machine power is capable of, the kind of energies that humanity develops, the way it creates, is capable of achieving godlike, but also hellish conditions. “Maschine & Energy” is the title of this exhibition. It presents a special cross-section of Thomas Ruff’s work, an intensified focus on the determination of the image through the camera and its dependency on the machine, lens, and chemistry.

For the last three decades (photographic) artists have been subjecting the traditional, confidently presented claim of photography to be a medium that depicts reality and objectivity to profound questioning, continually shaking the foundations of this old belief through their use and understanding of photography. The conceptual works implement media-critical, representation-critical, and self-referential approaches to investigate photography as a complex medium, they discuss photo-optical and photo-chemical processes and techniques, photographic equipment, the light, the carrier materials, as well as the photographic in general as an attitude, as a special, time-bound construct of perception. Over the course of his work, Thomas Ruff shows us how sensual, how pictorially powerful such an investigation can be. Machine world, image machines, and image research together generate a highly present, impressive likeness of themselves.