I remember an introductory seminar course at Zurich University I attended as a young student, with philosophy as a subsidiary subject. Theories of science were the theme, in particular Thomas S. Kuhn’s major work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In it Kuhn describes the development of science as a sequence of shifts between normal and revolutionary phases. His central concept is the paradigm, in simpler terms a concrete solution to a problem that has been accepted by professional circles. In this sense a paradigm shift describes a revolutionary phase of science in which understanding switches from an accepted paradigm to a new one, which is generally irreconcilable with the old concept.

What particularly stays in my memory is the image of a professor who until his retirement adheres to his basic ideas which he formulated at some stage in his personal career and develops only slightly if at all. But he will not allow fundamentally different, above all radically new “incommensurable” thoughts. Only on his retirement is a paradigm shift in teaching and research possible at his institute. If this professor has a leading role in research internationally, it can happen that he is able to block new ideas for a very long time, unconsciously or deliberately.

This week in the Zurich Tages-Anzeiger I finally read a conversation with Philipp Theisohn, a professor of literature, on science fiction, cloud computing, and technologies that replace nature. In it he refers to H.G. Wells, the author of The Time Machine. In the first half of the 20th century Wells wrote some 60 futurological non-fiction books in each of which he projected or thought ahead to inventions. At the end of his life, however, he declared these writings worthless because they could not have foreseen the economic crisis of the 1930s, World War II, or the atomic bomb, because they did not yet have even an inkling of those major interruptions. In the conversation Theisohn names the leap or break as the decisive factor in good science-fiction writing. Perhaps it is also the decisive characteristic for grasping global development.

Both ideas lodge conspicuously in my head when I think of Kodak or other large firms that have come to grief or even gone under in the past two or three decades. In the course of 100 years the Eastman Kodak Company transformed itself, step by step, into a photography empire. It began with the first roll-film camera – George Eastman’s famous publicity slogan said "You Press the Button, We Do the Rest" – and in the second half of the 20th century, with the color-slide films in the Kodachrome series, Ektachrome slide film, color negative film, but above all with highly sensitive Trix-X black and white film, it experienced tremendous worldwide dominance, and for a long time hardly any other firm could seriously compete with it. Kodak became a synonym for photography, at least for film and paper. Kodak was photography, was the most powerful brand within that industry. Kodak green even challenged our perception of color in nature.

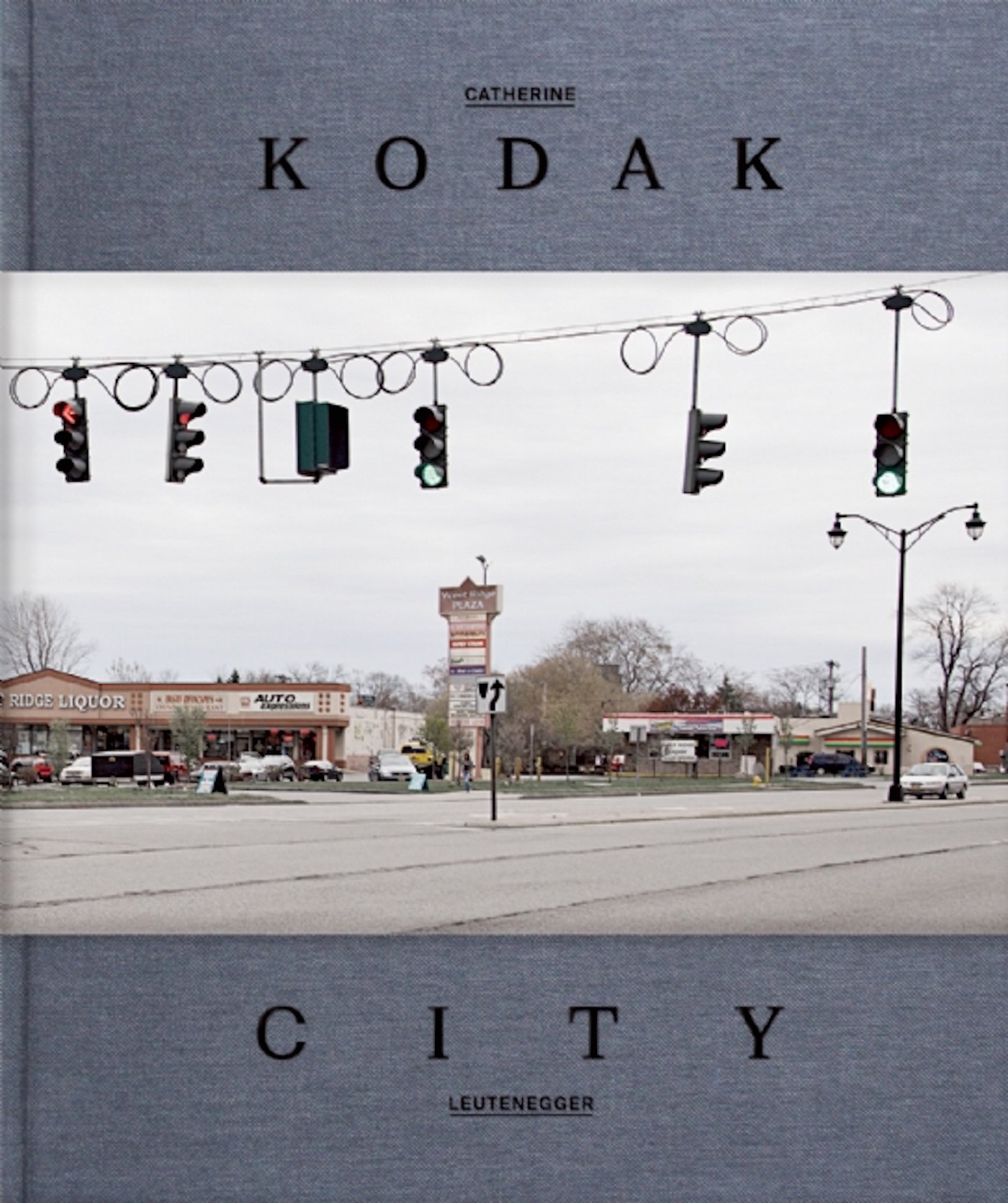

This Kodak empire did not successfully manage the move into the digital world. A.D. Coleman in his essay describes the history of this in much greater detail, and Catherine Leutenegger in an attentive, focused, calm way photographs how the collapse of a major firm has brought the whole town of Rochester down with it. A once innovative company tripped up in the transition into the digital age. The company became the – some say arrogant – colossus which steadily went on developing its products stage by stage, improving them qualitatively or economically, which was proud of its successes, but for that very reason made the necessary steps into the future only cautiously. Kodak did make tentative moves in the direction of digitalization, but ultimately trusted in its power in the traditional field. Many management mistakes were certainly made, but that is not is what is being discussed here; rather the firm seems to be a striking example of how the importance a looming, already under-way paradigm shift was wrongly assessed, or recognized too late.

In The Savage Mind Claude Lévi-Strauss uses the paired concepts of hot and cold societies. Cold cultures are societies that have been static, practically frozen, in which no social change is taking place any longer, which are so stable that they become passive, indeed crippled, that they ossify. Large companies run the risk of behaving like cold cultures, no longer as hot, constantly changing, fast developing societies, as they must have done at their own origins. In 1889, with “We Do the Rest”, Kodak revolutionized the rapidly developing photographic world; for the new digital worlds both the idea and the slogan were lacking.

At the beginning of the 1990s the photographic world was still almost totally analog. There was even a prevailing feeling that digitalization allegedly had nothing to do with it. The impetus with which it finally asserted itself is shown by these facts: in 1993 three percent of the global technological information capacity was handled digitally, in 2002 it was 50 percent, in 2007 94 percent, and today probably more than 99 percent. For a short time the digital age grew up quietly, then broke in like a flood, submerging the analog world. A technical revolution in manifest form, a powerful paradigm shift which completely revolutionized and keeps on transforming thinking, computation, production and communication.

For a long time that shift was played down in photography. “What does it really matter whether I put a film in behind the lens, or insert a digital back?” was a frequent comment from photographers. From the point of view of the producer, in the act of photographing, the change is perhaps at its least significant. Except that the photographer can now keep on endlessly shooting for as long as the hard disk lasts out, in any case ten or a hundred times more than previously. Except that s/he sees the image her/himself and is no longer groping in the dark. Except that s/he can send it the editorial department in “no time”, which again distributes it if necessary to the whole world in “no time”. Except that in the end s/he no longer gets any commissions because dozens of uninvolved people with their smartphones on the spot have likewise taken photos and passed on the images. This is illustrated by this fictitious situation: A car bomb explodes in Baghdad. Via geolocation and GPS today and in future it can be established which smartphones are on the spot. Seconds after the explosion 15 smartphones have been operated, one smartphone by chance during the explosion, while three smartphones have recorded the situation before the explosion. The data can be extracted from the devices and provide a complex, visual image of the event, from more perspectives than a single photographer could ever have done. The concept of the documentary changes as well as the idea of the photographer in the field and the concept of journalistic photography equally radically.

At the start of the digital irruption into photography it was above all manipulability of digital data that was discussed. In press photography for example as follows: The photographer to a great extent loses authorship of the image, because the picture editor can easily alter the photograph in a kind of post-production process. S/he can heighten the contrasts, alter colors, accentuate, and even make direct interventions in the image. At that time the notional coordinates were like this: Here the author, the honest photographer, there the manipulative (picture) editors, possibly also the manipulative firms and politicians aiming to load the theme not only in media terms, but politically too. In artifice-based photography the photographer him/herself again becomes the demiurge who can alter the photograph as s/he sees fit to make a photographic picture.

But we now find that drastic changes in digitalization are manifesting themselves mainly in other fields; that we are moving into new forms of artificiality, for example. In the interplay between the body and the image of the body, our inner images are also changing, and correspondingly the conventional boundaries. We attack the traditional integrity of the body, intervene, and not only in the case of illness; rather the continually evolving idea of the perfect body, the perfect face, makes us far quicker to reach for the knife. The popular media are full of reports such as “Every fifth person in this country, every fourth person in that country, soon just as many men as women are having interventions made on their body”. Right now we still note these interventions with astonishment, and insofar as they are visible, more often than not as an impairment of the natural appearance, but that will soon change. The more people who undergo such interventions, the more strongly the image of the surgically altered face and body will be perceived as sexy, daring, cool, desirable, because it is an achievable new ideal. Perhaps attributed with a new class distinction: Who can afford it, and who can’t?

What is actually going on here? How is it that forms of artificiality can become so sexy in the population at large? It works only because the world is changing into image. Because the image is becoming more central, more defining than prior lived experience, than physical reality. Oliver Wendell Holmes’s euphoric demand at the beginning of the history of photography that we should photograph the world so that we could experience it immaterially, and then burn it down, is already becoming a form of “reality” step by step in the analog, but particularly in the digital, virtual, mediatic world. The long path from substance to surface, from matter to sign, is entering a new phase. Science-fiction writers will rejoice: We are stepping out on to the path to the transhuman. The – digitally altered, polished, designed – models are having a reverse impact on the real nature of bodies, the artificial is gradually becoming a practicable form.

With reference to architecture I recently wrote: “Over the centuries structural shells became ever more delicate, until they were wafer-thin, until they were transparent. But it is only images that dematerialize buildings completely, remove the materiality from them, and reduce them to form and sign. The ultra-flat images of the selfsame buildings exclude voluminous materiality.” Eyesight has already increasingly dominated the other senses in the 20th century, digitalization finally completes the process of de-sensualizing the photographic image too. The alchemistic aspect of photography has disappeared, the darkness, the smell of chemicals, the red light, the real camera obscura, or darkroom. The image has been dragged into the light, disembodied, exhaustion has taken it over. It has remained as a mass of data, brilliant to look at on screen, a mass of data that can easily be channeled, animated, designed, and quickly distributed right across the world. And can also rapidly be endowed with a nostalgic atmosphere via Instagram or Hipstamatic, if the view forward is too chilly.

The industry is falling over itself in figures. In 2012 more photos were apparently taken than in the entire history of photography since 1839, counted together. On Facebook more than 300 million photographs are uploaded every day. Tumblr boasts far more than 60 billion entries, most of them photographs. The speed with which the images zoom round the world and can easily be multiplied makes even Speedy Gonzales, once the fastest comic mouse on the planet, congeal into a pillar of salt. What do we do with this quantity, and these speeds? At present minds are divided over this question.

We produce trillions of photographs, put them on line, send them round the world at the speed of light - one of the great possibilities opened up by the digitalization of photography and communication –, and nobody even looks at them any more? We take countless photos, but evidently most of them disappear in a sizeable attention deficit? The majority of them are hardly ever looked at again, others get a brief, pleasant greeting from a mini-community and are then forgotten; only a fraction of the mountain of images achieve a certain temporally and spatially limited importance, a screen or print presence, a place in a private album. Most photographs begin to go off from the very first second in the camera or on the computer, on to which they are loaded in packets, disorganized, unstructured. The moment of the shot, on the other hand, really does seem to be important, the circumstances of making image, the producing of the images, the communal clicking and giggling too, while the result is far less so. I wonder whether its own collapse, its own implosion, is not already inherent in the seemingly gigantic victory parade of photography? Whether the surging flow, stream, tsunami of images and the lightning speed with which the images surge around us do not virtually inevitably codetermine the future disaster, indeed conjure it up? But language is of course used to babbling too.

What function do these images really fulfil today? What to they try to be, should they be, must they be? Many of them seem hardly to assume aesthetic functions any more, but to act as social and personal psychological triggers with a running time of 1, 2, 3, 4, at most 5 seconds. Instead of remembering: take a photograph. Instead of experiencing: take a photograph. Instead of thinking: take a photograph. Instead of knowing: take a photograph. Instead of talking: take a photograph. Instead of loving: take a photograph. Instead of reading: take a photograph. You are familiar with the situation where visitors at exhibitions photograph explanatory texts, thinking they will then read them at home. Taking photographs seems here to replace the original experience.

In this field of thought digitalization leads on the one hand to a displacement of the perception of photography and on the other to a displacement of our actions with/because of/by means of photography. Aesthetic aspects are far less important than event-rich, mnemonic, aspects, ones archiving the present. These changes in behavior could be the most drastic consequences of the digitalization of photography. But the scope of the digital revolution cannot yet really even be foreseen, at least not for an observer whose personal paradigmatic foundation and formation took place in the Seventies and Eighties of last century (like those of the author of this text), and who therefore continues to look with amazement, fascination, but also a slight shudder at the cool digital stream of images. But I enjoy the works by artists on this theme that are now becoming much more solid and complex.

Today picture rights for a family photo of the “Brangelina” family, according to the visual surrender of the youngest offspring, cost three and a half times more than very dearest photograph in the history of photography. More than 14 million dollars as against the 4.3 million dollars that were paid three years ago at an auction for a photograph by Andreas Gursky. Thus today the use value of images clearly triumphs over the aesthetic value to collectors: use beats aesthetics. Photography is dead! Long live photography!