PAUL (Astonished)

They're all the same.

AUGGIE (Smiling proudly)

That's right. More than four thousand pictures of the same place. The corner of 3rd Street and Seventh Avenue at eight o'clock in the morning.

Four thousand straight days in all kinds of weather.

(Pause)

That's why I can never take a vacation. I've got to be in my spot every morning. Every morning in the same spot at the same time.

PAUL (At a loss. Turns a page, then another page)

I've never seen anything like it.

AUGGIE

It's my project. What you'd call my life's work.

PAUL (Puts down the album and picks up another. Flips through the pages and finds more of the same. Shakes his head in bafflement)

Amazing.

(Trying to be polite)

I'm not sure I get it, though. I mean, how did you ever come up with the idea to do this ... this project?

AUGGIE

I don't know, it just came to me. It's my corner, after all. It's just one little part of the world, but things happen there, too, just like everywhere else.

It's a record of my little spot.

PAUL (Flipping through the album, still shaking his head)

It's kind of overwhelming.

AUGGIE (Still smiling)

You'll never get it if you don't slow down, my friend.

From the script of the film Smoke by Paul Auster (1995)

Views – be they landscapes or seascapes -- are integral to the imagery of the western world, to our ways of seeing, our dreams and fantasies, and to our real and fictional lives. It has been so ever since we abandoned our union with a deity, dividing everything into heaven and earth, me and you, self and world, thus creating a complex system of existence and perceptual possibilities.

When Petrarch ascended Mont Ventoux, Provence, in the mid-fourteenth century and penned a lengthy epistle, de curis propriis [On Personal Concerns] – to the Augustinian monk Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro, what he was doing was rising above the earth, removing himself from the great oneness of the world and admiring, for the first time, nature as landscape, viewed from afar. It was an act that broke with the unquestioned God-given union and the divine order of things – an act that marked the birth of the autonomously seeing, thinking, acting individual confronted with and observing the world spread out before him.

Caspar David Friedrich’s painting of The Monk by the Sea teaches us that the path towards such autonomy is strewn with the pain of separation and with many other fears. We see the monk standing on a promontory, gazing into the distance across a dark and desolate ocean, into the boundless expanse of nature: a lost and solitary being, cast out from the oneness of the world, utterly alone. What Friedrich portrays here is not so much nature itself as a single overwhelming feeling. Instead, four hundred years after Petrarch, the Romantic era heralded the culmination of that division of unity and, with it, a realignment of our worldly existence, bringing in its wake a profound sense of uncertainty, a sense of being cast adrift, abandoned, lost and completely separated from the wider context of meaning. Johann Gottfried Herder had confidently posited just a few years earlier that "each human being has his own measure, as it were an accord peculiar to him of all his feelings to each other“ and that "the deepest ground of our being is individual, in feelings as well as thoughts.“

Ultimately, however, it was the Industrial Revolution that was to sunder mankind’s earthly existence by driving a wedge between the cyclical life experiences of space and time. The natural unity that had once held sway – living and sleeping in the same place, embedded within the cycle of day and night – now gave way to a new order: the order of the factory shift in which, for the first time, work and life were measured, quantified and standardised by the clang of the factory bell, by the checks at the factory gates and by the routine of clocking in and out of work. This was a radical departure from a life that had previously followed the rhythms of nature.

During this time, the notion of landscape as a grand, unspoilt, sacred expression of Nature writ large began to take shape in photography (especially in American photography). It was idealised and stylised as the very embodiment of the eternal, the enduring, and the divine – generated solely through its own forces of sun, rain, snow and storm. Landscape became the sacred and inviolate body of nature in contrast to the accursed filth of the body urban. It was here that the psyche of the postulated subject forged an escape route, as it were – a refuge from the originary, a surrogate for paradise lost. That psyche glimpses the divine in unspoilt nature. This is why, in her book Landscape as Photograph, Estelle Jussim speaks of "landscape as god", as an exaltation and a symbol.

In his earlier book Il Cerchio, Jan Jedlička touches on something of this sacred element as he explores the singular landscape of the Maremma, which lies between water and land, constantly merging into new forms in which the water, since the days of classical antiquity, has defied even the most strenuous efforts of humankind to make it arable and fertile throughout the course of a seasonal cycle that runs from winter to winter. We see how the wind scuds across the plain, how the surging tides heave driftwood to the shore, reshaping the landscape over and over, and how the temperature gradually rises until the sun beats down upon our heads relentlessly in high summer in spite of the cool sea breeze. Jedlička touches very subtly on the ways in which the forces of nature and the constructs of humankind meet one another, rubbing together until the colours fade, the wood bleaches and the structure crumbles. His square, black-and-white photographs, sometimes in dramatically wide-angled shots, slip through the tides of time and the forces of nature that build up, surge, break through, emerge afresh or leadenly endure. From the landward side, he follows the traces of human activity outside the tourist season and, during the tourist season, the traces of the tourists themselves. However, the minimalist approach of his photographs, whether individual or in series – most of them featuring a horizon line that either divides the image in the middle or binds it together – preclude the emergence of any grand or symbolic symphony of nature. Instead, his pictures seem like laconic accounts of the passing seasons: quiet, simple, even modest, and yet painstakingly aligned.

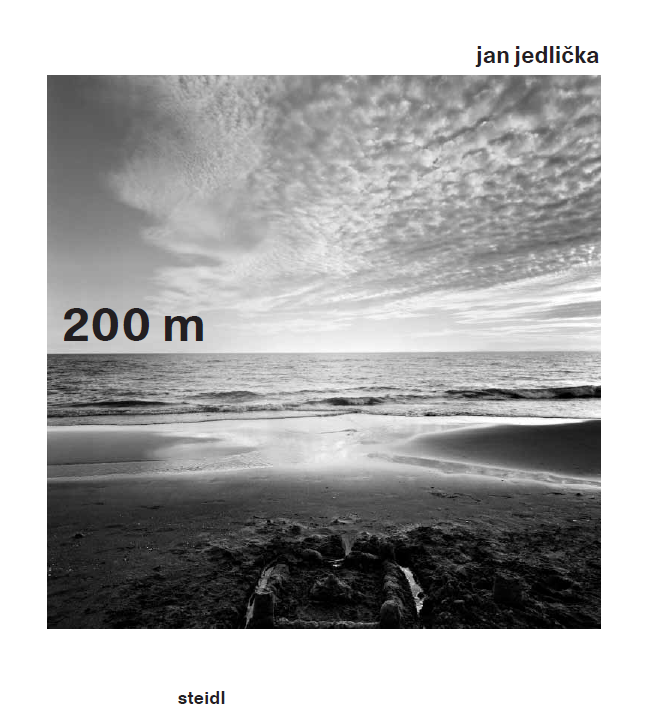

In his latest book, Jan Jedlička has developed a different tonal approach. His photographs are still analogue, black-and-white, square, shot with intense focus on black-and-white film and then developed using a colour process (which, combined with the rapid and precisely focused hand-held shot, results in strong contrasts) and they follow one another in a quietly imperturbable sequence. Yet their constraints are drawn more stringently than before. Here, we find only a small section of beach, a strip of land stretching just 200m – that is to say. 200m from left to right, from south to north, on the fringes of the sea, from the water to the land and back again – specifically, at Principina a Mare, right next to the Parco Regionale della Maremma. Two simple little indices, multiplied to an area of 40,000 sq.m. Or thereabouts – for who would apply scientifically precise parameters to nature, let alone to the observation and perception of nature? It would be a stark reduction, one might initially conclude, to press reality into such a schematic paradigm, to so narrow the view or even block it in a way that might rob it of its nuance and subtlety. And yet, there are times when such limitations actually sharpen the gaze and alert it to small and seemingly insignificant, everyday details. They can permit us to focus on the trivial and the banal, on the little things that so often pass us by, quite casually, in the ebb and flow of life.

The first picture in the series stakes out the territory: it marks the field of play with little wooden staves, defining the area within which the life that we observe unfolds according to seemingly random or invisible laws. The second picture reveals the potential and boundaries of nature, with the flight into infinity of sand, water and sea like so many converging discs. The light is all but gone. Only on the horizon do we glimpse a shimmer of hope for better things. Within the picture plane, perspectivally viewed, various fields of grey converge, energised only slightly by a horizon line sloping down towards the left. The solitary figure by the sea in a photograph further back no longer gazes with yearning into the distance. Instead, the position of the arms suggests that this is someone focused on a smartphone, whose virtual reach oversteps by far the physical radius of the staked-out boundaries. The third picture gives an impression of surging water masses that threaten to swamp the image, pushing sky, sea and sand into almost one and the same dimension as though all boundaries were falling apart to form and symbolise a whole.

And with that, life really gets going. First, nature kicks in, forging paths, forming ponds, beaching driftwood, opening the way to utter abandon. While the first surfers of the season are still battling with fearsome gusts, the time comes to sweep the sand from the basketball pitch, plant the first tentative footprints in the sand leading seawards. There, at the edge of the water, people pass to and from like silhouettes in either direction. Sunshades and deckchairs appear, facing the sea, accompanied by ever more signs of playfulness, fun and joyful idleness. Highlights include bold excavations and sandcastles, overseen by translucently shimmering kites floating aloft, by people lulled into laziness, and by those determined not to be distracted from their goal of simply enjoying the here and now. As autumn approaches, the beach gradually becomes deserted. The deckchairs disappear, and the traces of man and nature blend. The parking spaces are abandoned, the occasional walkers seem all the more solitary, and a touch of melancholy slowly descends upon the place, swelling to an ever more palpable crescendo. It is as though the sea were winning back its realm.

With the help of the sunlight, camera lens wide open, focusing his constant gaze upon the sea, Jan Jedlička brings a touch of serenity, a hint of levity and a joyfully ludic character to the field that he has staked out. In these images, he seems to embrace the infectious lightness of being, right here by the seaside, warmed by the sun, his feet the sand and salt air in his nostrils. Here, for a moment, he seems to be able to forget the burdens of life. And in between, using a different camera format, he produces square photographic abstractions, views of traces in the sand, clumps of grass and reeds, crowned here and there by traces of salt or foam. These almost monochromatic, abstract, two-dimensional images encourage the viewer to take a second look at each and every photograph by Jedlička – to observe each picture both in the sense of the strongly seductive approach that immerses the viewer completely in the brilliance of the imagery, and at the same time in the sense of overcoming that illusion by actually taking a more pragmatic approach: actively engaging the senses of sight and smell and touch in order to explore the signs that spread out across the paper. On the surface of the print, each and every photographic sign contributes just as much to the perspectival illusion as it does to the concrete signifier.

As the shadows lengthen and deepen, dark dots scatter across the sand. There is no respite far and wide. Autumn and winter are approaching and nature is taking control once more. In his book 200m, Jan Jedlička develops a chamber orchestrestral performance between human life and the various forces of nature – the sun, wind and rain – and between the endurance of these forces pitted against the ludic joys of humankind. It is quite literally like playing in a sandpit – a wonderful, 200m by 200m experimental sandpit; a device deliberately chosen in order to focus all the better on this interaction, encapsulating the sense of relaxation, of letting-go, in playfulness, enjoyment and detente.

Finally, Jedlička presents an image that captures the confused mass of footsteps imprinted on the sand. Tipped into the vertical in a book or on a wall, these imprints conjure up the inscriptions of an Ancient Egyptian temple, recalling signs from some distant epoch – like the gritty murmur of archaeology itself. Yet this is the archaeology of the contemporary, which tells of present-day people in search of expanses of water and space, yearning for the carefree life that has become the sacred serenity of our times. And there is also a trace of that human aspect in the face of some impending disturbance or approaching storm, seeking to maintain the right to indulge in sheer pleasure.

Translation Ishbel Flett