The cause of photographic abstraction did not go away. For some considerable time photograms took the lead (sometimes misleadingly, as in the hands of Moholy-Nagy),6 but there were also the black squares, circles, triangles created by photographic means in the wake of Malevich’s paintings, there was Alexander Rodchenko’s Black on Black, an oil-photogram as a black surface, and Gottfried Jäger’s “generative photography” in the 1960s, 70s and 80s – self-generating photographs with their own (generative) aesthetic. But they lacked the will to make their mark, they failed to recognise the need to take seriously well-founded doubts. As yet supply and demand were in balance; film production, picture printing and press imagery were rattling on and blinkering our vision with appealing, representational pictorial worlds.

But in early 2011 Volume 206 of Kunstforum international highlighted a new tendency towards abstraction and addressed its readers: “This current is apparent in all the various media and seems to be more than an art-immanent debate. But what is it that is specifically new about this new abstraction? Is it really about as-yet unknown thematic directions and concepts or is it merely a contemporary variant or re-interpretation of already established artistic strategies? And what does it tell us, when artists once again turn to abstraction? Are they, in so doing, considering a withdrawal from reality, an aesthetic escape, seeking some form of compensation, or are they rather mediating a counter-plan, renewal and a utopian quality?”7

Ever since Jean Baudrillard we have seen how signs and their meanings have increasingly drawn apart over the years, that the signifier has become much more important than the signified. We live in an ocean of free-flowing, referenceless signs, which are available for anything and everything. The digitalisation of the world of signs, that is to say, the photographic world, has led to a positive eruption of blurring. We live in a world of simulation, in a “simulacrum”, that makes it impossible to distinguish between original and copy, model and likeness, reality and imagination. Signs and images are increasingly bereft of references.

Now, for the first time, it seems that abstraction in photography is being taken seriously and properly debated; it is regarded as important in terms of media theory and photograph-ontology. Now, at last, people recognise that in fact every photograph is abstract, that any reference to reality is “merely” a pleasant, comforting guise, that “all photographs are, to the same degree, representational, concrete and abstract; constructions that arise from translations and manipulations”.8 But these days there is an awareness and an ongoing enquiry into the fact that the term “abstract photography” is no more than a holding-concept, for in itself it is too simplistic, too empty, to encompass the realm of possibilities of this genre. What Ugo Mulas, Sigmar Polke, James Welling, Adam Fuss, Herwig Kempinger, Wolfgang Tillmans, Walead Beshty (to name but a few of its leading exponents) are aiming at and referencing with their photo-abstract, photo-concrete sign-worlds is as starkly different as landscape photography and portrait photography once were, as different as war and peace, as Heaven and Earth. Yet all are in no doubt as to the fact that every photograph is a construct and should be regarded and understood as such.

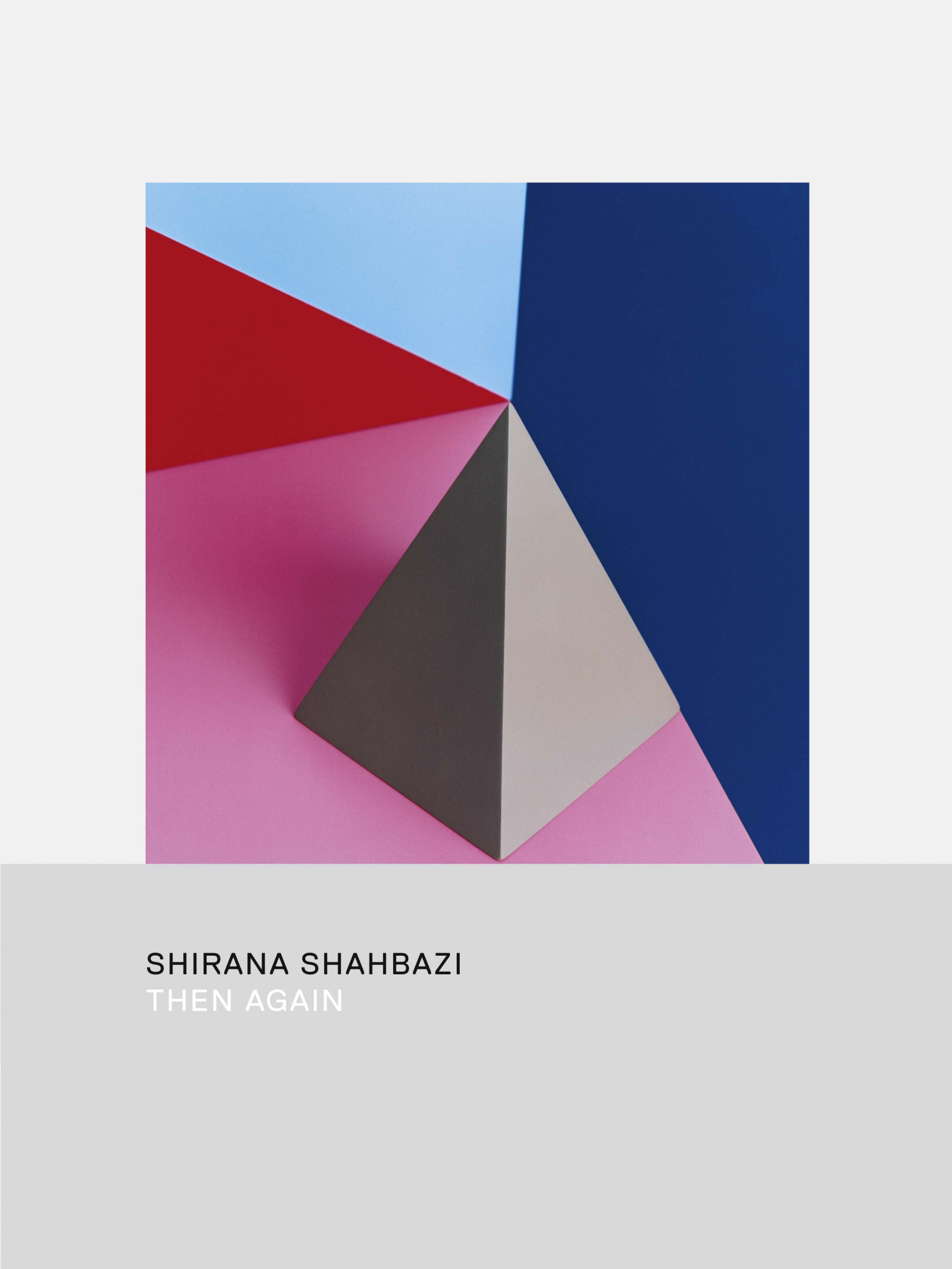

“We’re not creating a world, and that is not even what we want to do. To operate, thinking creatively, is enough for a start, perhaps something new will come of that, only it won’t, for sure, if it is meant from the outset to match some new vision of the world; it will only happen of its own accord, hopefully it might run off the rails in a good way, spawning wonderful bastards.”9 These sentiments from the German painter Bernd Ribbeck reflect one of the underlying currents in the new interest in abstraction, in which Shirana Shahbazi features ever more prominently.