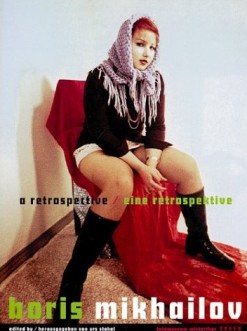

Surreal superimpositions, folk-artsy hand coloring, amateur snapshots, banal photographs with diary-like notes, staged self-portaits, naked in front of a black background, and immediate, hard, loud color photographs: Boris Mikhailov presents a dense and very diverse oeuvre that has filled his audience in the East and in the West with enthusiasm, sometimes mixed with irritation or consternation. It consists of around 25 groups of works, besides smaller works and single images, and covers a time span of more than 30 years, from the time of “developed socialism” in the 1970s to the collapse of the Soviet Union around 1990/91, the subsequent years of the “Wild East” and the time since his move from Kharkov, Ukraine, to the West in the late 1990s.

His work was hardly ever shown in public until the early 1990s. As an unofficial photographer, Boris Mikhailov was ostracized by the system of prescribed subject matter and representation, even more so than the unofficial artists. Although there was no formally decreed interdiction—apart from the requirement not to photograph events from above and not to show Soviet life in a manner that would devaluate its achievements—Boris Mikhailov was often reproachfully asked by Soviet “common sense,” even common people on the street, why he was taking pictures here; that this was not allowed; this was usually accompanied by the order to “expose” the film, i. e. to take it out of the camera in front of the militia who were quickly on the spot. Consequently, his photographs were not exhibited for a long time. There was no platform but his own small apartment or his friends’. These were tiny exhibitions for a limited time, yet they were intensely discussed among circles of friends and artists. This exchange also worked in banishment: Boris Mikhailov from Kharkov, Ukraine, was thoroughly familiar with the discussions among the Moscow conceptualists around Ilya Kabakov and Eric Bulatov. They knew his work as well and commented on it.

In 1990, with the opening of the East, Boris Mikhailov’s exhibition history starts, among others with a solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tel Aviv. Starting in the mid-1990s, he received numerous important awards (among many others, the Coutts Contemporary Art Foundation Award, the Hasselblad Award, and the City Private Bank Photography Prize). Since his shows at Forum Stadtpark, Graz (1992), the Rotterdam Biennale (1994), Portikus, Frankfurt, and the Kunsthalle Zürich (1995-1996), and the publication of his books, his work has been the subject of intense discussion in the West. It was exhibited in important places and found its market. The official reception in the East, with the exception of a show at the Soros Center of Contemporary Art in Kiev, was slow to start. Now, in spring 2003, a circle was closed: Boris Mikhailov received the first “General Satellite Corporation Art Prize for a contribution to the development of contemporary Russian art,” a new and important Russian art prize. The “lost son” was invited to come home again. Finally, he gained a recognition in Russia equal to the one he had enjoyed in the West for the past ten years.

Now his work is celebrated and discussed in both East and West—but do people in both places perceive it in the same way, and do they like or condemn it for the same reasons? This question accompanies this retrospective book, and it poses itself anew with every work and every essay. Boris Mikhailov himself points out the differences of perception in an interview with Victor Tupitsyn (pp.xxx), where they talk about the difficulties of finding their ways in the West: as an Eastern artist who grew up in the Soviet collective, in the Soviet system of communication. It took him five years before he could produce any new work, Mikhailov says. “[In Russia] I understand things. Everything, the pain. There’s more open feelings, open relationships, complicated relationships. But here I probably don’t understand everything. Not so much because I don’t speak the language, but because situations remain unclear to me.”(1) The difficulties of the artist are mirrored in our reception and perception of his work. In the West, we are unable to dissect his work as precisely as Boris Mikhailov does in conversation: references abound, to the meaning of this or that, within a narrow or a broad context. But even if we understood every cross-reference, every ulterior motive, every frame of reference, a difference would always remain: we don’t share the same pain, the same threat, the same avoid and boredom. But obviously his work offers a more universal point of entry, outside of its precise place within a Soviet context.

Methodically and thematically, it can be divided in four major periods that correspond to the social and political developments from “developed” socialism to “paralyzing” socialism under Breshnev, from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the ensuing decay of social order in the Ukraine:

First, the time of ruptures, of underlining / stressing, and of montage as a method of creating images (in the 1970s). Boris Mikhailov examines the hegemonic visual language of Soviet culture, among others its concept of beauty, the combination of “well done” (achievements), “painted red” (visual language), and experienced as “beautiful and right.” His “rupturing” of the hegemonic wall of signs allows doubt, conflict, and opens up a field for questions.

Second, the time of the banal, simple, unspectacular image (in the 1980s). It is the time of twofold authenticity. Boris Mikhailov was searching for an authentic and immediate visual language that would no longer define itself by deconstructing official visual language. It shows the country, life in the Soviet Union without the pomp, without the decorations, without Soviet language. The images talk about a Soviet Union without Moscow, about Soviet cities with main streets and town squares. They show mundane everyday life and approach the subcutaneous layers of the Soviet Union. Boris Mikhailov is turning into a phenomenologist of time, of the non-event, of serene and often burdensome boredom.

Third, the time after the collapse of the Soviet Union and his requiem in three parts on the decay of social order, first By the Ground, then At Dusk, and finally Case History (in the 1990s). Together, the three works—despite their varied visual rhetorical means, like panoramic photography as opposed to vertical portrait photography or brown and blue coloration as opposed to in-focus color photographs—are a great lament—sometimes mute and subdued, sometimes loud and shrill—on the decay, the collapse of order (By the Ground), of hope (At Dusk), and finally, of mundane, simple existence (Case History).

Fourth, the time of re-orientation, of the way out of the Soviet collective, which finally led to his move to the West (late 1990s). This period overlapped with the decay of order, as the collapse of the Soviet Union spat out artists like Boris Mikhailov: walls, roofs, figures of speech, the entire social edifice, they were all gone, and everyone was transformed into an individual who had to find the meaning of work entirely in the self, a great existential “being thrown into the world” (Geworfenheit).

But what is this “self”? Boris Mikhailov addresses this abrupt re-orientation in a theatrical staging of the artist as aging, ridiculous man, as a fallen Soviet being, as a doubting thinker, as an artist with an enema. I Am Not I is the representation of an identity crisis as a grotesque, full of questions and doubts, full of despair and laughter. As a kind of counterpart, Mikhailov created TV-Mania a few years later, the first of his works created in the West, in which he shows the quest of the artist to reorient himself, to understand the world by means of the oscillating signs on TV—the world, fragmented and scattered by the media’s image world, but broadcast 24/7 all over the globe.

Four periods, which are at the same time work spaces in whose aesthetics individual and collective frames of mind manifest themselves. I will now pick out some of the characteristics of the early work that will later be discussed in detail by the authors of the essays. As if predetermined by his life experience—he lost his job as an engineer because they found photographs of half-naked women in the company’s photo lab; as if motivated by his dual origin as Jew and Ukrainian like Mikhailov indicates in conversation: rupture, superimposition, and alienation are the morphological characteristics of a large part of his work, they are method and content at the same time. The gold-colored Lenin bust at the beginning of the book (taken from the unpublished series Susi and Others) was photographed from straight above. Consequently, Lenin’s facial features are distorted and hard to recognize. The photograph is not the requested deferential portrait, but a “punch” in the face of a monument. The oversized head is swaying above the snow-covered landscape as if theory and praxis, intellectual superstructure and material base had lost any contact. On the page opposite in the book, a naked woman reclines in frivolous and amusing pose and shows her behind to the “surrealist-convulsive” Lenin. A two-fold inversion, two off-beat, slightly coarse views on two scenes—and the stability of the social body “Soviet Union” is suddenly under suspicion.

“Through the ass of this woman I saw the world,” Mikhailov remarked his work group Superimpositions, each a sandwich-like layering of two disparate images. The early montages, with which Mikhailov became known in the Soviet Union, are not constructed to create a synthesis, like those of the Russian constructivists, Rodchenko’s for example. They deconstruct, dissolve stable states, crack them, dig holes, tear down the wallpaper, soil the “beautiful,” and create an expected, disturbingly open meaning. These montages are closer to the methods of surrealism than to those of constructivism. Boris Mikhailov rouses sexuality to soften the solidification of the visual world, the prescribed meanings. Woman, the naked, the private, the personal, carefree spare-time (in his images of the beach, of summer vacations)—these “dissident” elements gang together in a conspiracy of images and form a counter-image to the prescribed aesthetics as an expression of prescribed politics and thinking. They assign different values to the way things are, they dissolve by contradiction. The fissure in the image, the point of fracture opens up a view onto another level.

The series Red, Luriki, and Sots Art operate in manner contrary to the Superimpositions. They do not confront disparate image with each other—they rather underline them, double them, stress them, and create their own kind of shifting and alienation. Luriki consists of found photographs, hand-colored by Mikhailov. This treatment and their selection accentuate, distort, and ironize. In Luriki, he takes up the Russian predilection to color beloved photographs. The series Sots Art that consists of photographs of his own with the charm of provincial press photographs, looks like Eastern Pop art because of its use of loud colors. In the Series Red, however, the documenting gaze attentively, seismographically even, traces every little speck of red in the Russian-Ukrainian landscape, from coats of arms to all the symbols of the Soviet Union to people’s everyday life, from the official to the private, from the ostentatiously displayed to the hidden, and visualizes the saturation and thorough coloration of the social body. In this complex series, the color red becomes a kind of “essence” that functions as a secular “all-encompassing” instance of Soviet life. Red ccompanies human beings from the cradle to the grave (cf. Margarita Tupitsyn’s essay, pp. xxx).

With the work Beach of Berdiansk. Sunday, 11 am to 1 pm (1981), Boris Mikhailov’s visual strategy markedly changed, it became more documentary, more journalistic. He found a form close to a visual diary. What first started to become evident in Dance (1978; cf. Mikhail Shishkin’s text, pp. xxx) becomes a central feature here and subsequently in Crimean Snobism, Horizontal Images, Vertical Horizons, River Pastoral, City Without Main Street, and Unfinished Dissertation: color disappears, and with it the manipulation of images, their treatment, their layering, their metaphoric intention. The images become black-and-white and simple, calm, and direct. They just show what is here, not more. They are banal observations: a part of a street, a meadow, a backyard, the front of a building, people crossing a town square, jumping and playing children, a couple of trees, some sun rays. The images document the everyday, the “not special,” the non-event. They show Boris Mikhailov’s ways to the sea, to the countryside, to the city. These images penetrate the messianic world of signs or they shun it, bypass it. They touch upon other layers, they move along an axis of time other than the Soviet one. The idyllic village on the countryside (River Pastoral), the calm, almost empty city (City Without Main Street)—everything is gray, empty, a little bit shabby and dirty, but the images also exude a sense of calm and equanimity. A serene boredom on the countryside, a more oppressing boredom in the city. Peculiarly Soviet characteristics have disappeared; what remains is the feeling of a time that will outlast disorders, an “even condition.” In this group of works, two pictures are always printed on one sheet of paper. Initially, an attempt to save paper, it now turns into an aesthetic principle. And two times two photographs make a group of four on a double page. The four images, with often only slight shifts of the viewpoint, show a scenery, a landscape, a small forest, a playground. The shifting of the viewpoint underlines the passing of time, the “now and a little bit later.” The four images seem like minuscule film scenes with a hint of a narrative and sequence. In Series of Four, Boris Mikhailov conspicuously reduced and conceptualized the arrangement, combining the four images in a new single image. In River Pastoral and City Without Main Street, the arrangement seems relaxed, incidental, like a casual story—the happy serenity of a political and private period of life.

Mikhailov began this period of his work with Horizontal Images, Vertical Calendars, a voluminous group of images to which he added hand-written comments—lapidary comments on events, remarks on his photography, witty observations or thoughts, for example: “It was warm for the first time, the air was full of intoxication. You were feeling as if through a sieve. Everything belonged to you, and everything was ephemeral.” Boris Mikhailov and his work entered a new stage. He no longer just searched for “opposition,” but for the fundamental, the authentic, simple relations between things, humans, himself and the world. He turned into an attentive phenomenologist of things, of relations, of time. He observes, he lets things happen, he makes you think—without drama and almost casually, the photographs and the notes supporting each other.

Mikhailov uses the combination of image and text, of photographic observation and written notes once again in Unfinished Dissertation. Two photographs are pasted on the backs of the pages of a found, unfinished dissertation, accompanied and framed by pensive, reasoning texts. All of these pairs of photographs talk about slight differences of time and place and sequence, about small, almost imperceptible shifts, the spaces in between. The texts accompany them on different level. They read like a fragmentary, artistic monologue (cf. the essay by Ekaterina Degot, pp. xxx).

In this period, the coarse, the deliberately ugly disappears from his visual world. Mikhailov describes it as stable period in his private life and as a stable, but boring time on a collective level. The last years of Breshnev’s agony: politics were waiting, the population was waiting. Nothing happened, a tonal mid-range, even boredom, weighing upon everything like fog. Exterior Calm. A great void. But it was not an extreme or panicky time, not a time of crying out like the time of the discovery of Stalin’s atrocities or the invasion of Czechoslovakia. Consequently, Mikhailov deferred coarse and vulgar visual rhetoric—until the time after the collapse of the Soviet Union, until Case History, his documentation of decaying existence. In Case History, he almost mercilessly uses sharp, immediate, precise, and open documentation, as if he not only wanted to capture the misery of the Soviet social body and its decay in the 1990s, the agony of individuals, but also the millions of famine victims in the Ukraine of the 1930s, as they were never photographed and are now slowly being forgotten. He shows the wounds on the social and private body, a bruised head. Not as signs of redemption, but of creeping, festering, inflamed decline (cf. the essays by Helen Petrovsky and Anne von der Heiden on By the Ground, At Dusk, and Case History, pp. xxx and pp. xxx).

The strategies of eroticism and of the sexual body, looking with and through the female body, run merrily and obsessively through Mikhailov’s entire oeuvre. Woman is resistance against the solidly built, the predominant; she is the “hole in the wall,” the break-up—she is, after all, the energy of life, a counter-force against the latent Russian pessimism in his work. His own appearances and those of his wives fulfill a similar function, even when the fundamental approach is strictly documentary (cf. the essay by Inka Schube, pp. xxx). Laughing and joking, he appears as a kind of harlequin—sometimes dandy, sometimes jester, sometimes lazy macho. During the moment of his appearance, he relieves the heaviness of burden, the bluntness of boredom; he brightens the viewer up and plays little pranks with himself and us. His appearances transform his photographs into a theatrum mundi; the documentary photographs no longer immediately reference reality because the things he shows, their appearance and likeness, are not the focus of his interest, but rather their function in the “being of the world.”

His multi-layered, rich work shows Boris Mikhailov as a surrealist eroticist, a lamenting singer, a laughing jester, and a phenomenologist of time, who created an ever evolving work within a historical context that across all borders presents a moving image of the hurt human soul, full of humor and seriousness, at the same time calm and grotesque.

1.) From a conversation with Marina Achenbach, in: Boris Mikhailov, Äußere Ruhe. Drucksache N. F. 4 der Internationalen Heiner Müller Gesellschaft, Düsseldorf 2000