“In seeing less, more is imagined.”1

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Photography bolsters the sense of sight, favors a positivist attitude toward the world, and is a mainstay supporting the triumph of the visual. Photography visually substantiates the turn toward both the temporal and the superficial. It apprehends the world optically, exploring it in the belief that it will be able to make use of superficial signs in order to produce statements about what lies behind the signs themselves. This process could be called the “photographic search for evidence,” referring to the new methods for detecting evidence that developed during the nineteenth century at the same time that photography was evolving. Surface criteria were collected and combined in order to discover truth in the sum of the individual details. Truth was sought in painting, art history, criminology, in Freud’s concept of the psyche, in the world as seen by photographers. Régis Debray summarized it in his book Vie et mort de l’image: “We are the first civilization to believe that our cameras authorize us to trust our eyes. The first that has set up an equation between visibility, reality, and truth. All of the others—even our own until just recently—believed that the image hindered our ability to see.”2

No sooner had the principle behind photography been discovered and the photographic process invented, than photographers began shooting pictures of things here in order to show them there. In the nineteenth century the first photographers presented the world from a mostly quiet, unmitigated, and dignified distance. The use of smaller cameras, rolls of film, and flash bulbs roiled this calm, and for the first time, the intact character of the figure was attacked. Photography then “discovered” the buried, the hidden, the snapshot revealing the unexpected: the beggar on the curb, the lovers kissing, drops of milk upon impact. New kinds of film, large telephoto lenses, and electronic night vision devices soon began to disturb the private lives of film stars as well as the purity of outer space. With the possibilities provided by electronics, exposure becomes total. For the first time, we have a very clear view of the fact that researching and discovering things and relationships by examining their surfaces—supposedly a noble attribute of the photographer’s activity—is only one side of the coin. The other side is comprised of depicting, showing off, presenting, revealing. This has always been the case. It is just that we have gradually shifted from an appropriate, “decent” distance from the world to its opposite: a shamelessly corrosive, close proximity. The porno(foto)graphic view crosses all borders, cuts things up into pieces right in front of our eyes, advertises frantically, rapidly.

Hence, taking the path to visibility through photography moves us from a distance to close up, from the overall picture to the detail, from discovery to depiction. In the process, the photographic image becomes increasingly more specific: sharper, more detailed, more precise. Its realism is so effective that it is like a certainty in time and space, a truth. Yet we overlook the fact that what has existed in the past does indeed leave behind a trace in (analog) photography—that a past event or existence creates an optical, chemical deposit that can be seen in a photograph. However, this trace of existence or time tells only one truth—namely, that something has occurred and been visually perceived. Yet it does not tell us how, where, why, and in what context something happened. And generally, we overlook the fact that this way of getting closer, of achieving more specificity through photography, this concentration on the visible, is paradoxically connected with a kind of retreat. We begin to withdraw somewhat from the world. We are less oriented toward a world that can be touched, smelled, heard, experienced, and imagined, and become more attuned to optical signals and visual information. We turn the visible into an absolute at the expense of other perceptions and experiences.

Kyungwoo Chun works with visual tools, with photography and video. Yet in his work he seems to be following a path that moves in a direction opposite to what I have just described. In many ways, this path leads back; it is as if by following it, he is attempting to complete a circle. At the age of 49, General Chun Man Ri went from China to Korea to fight there in the service of the Joseon dynasty. After fulfilling his mission, he unexpectedly remained in Korea. Around four centuries later, the general’s descendent Kyungwoo Chun returned sixteen generations afterward to the place where the general came from, to his native region, which is therefore also the place where Kyungwoo Chun himself originated via his ancestor, long ago and far away. In three villages in the province of Henan, where the Chuns live, he created an analogy to the name of Chun, which means “thousand.” This analogy was a small “army” of one thousand villagers. In company with him, they were, on the one hand, a symbol for the thousands of Chun ancestors, and, on the other, they symbolized the general, whose mother gave him the name “ten thousand thousand leagues.” Kyungwoo Chun was more cooperative and democratic in his actions than his ancestor probably was. Even though there is visual uniformity, since all one thousand of the portraits were photographed in the same way, participation in the action was voluntary. Additionally, Chun’s act was visually and symbolically organized, and not existential. It is part of a history that deals with history.

By updating nineteenth-century portrait photography, whose materials were very limited in terms of their sensitivity to light, Kyungwoo Chun unreels and reveals the history of photography in reverse. He completes a circle, returning to the beginnings of photography, when people sitting for portraits prepared and clothed themselves in a manner befitting the occasion. In an old studio, backdrops and props were selected, positions and poses were tried, and finally, the lighting was arranged. Most studios used daylight, because at the time artificial lighting was still insufficient. Lastly, props to assist the sitter were brought: footrests, headrests, armrests, depending upon the position of the sitter. These tools were necessary because the photo materials were not particularly light sensitive, and so it could take thirty seconds or more to make a portrait. During this time, the sitter was not supposed to move, so that the portrait would be as sharp as possible, freezing the sitter’s identity. In the early days, however, the frozen pose was never quite perfect: one can always perceive a hint of the passage of time in these old pictures.

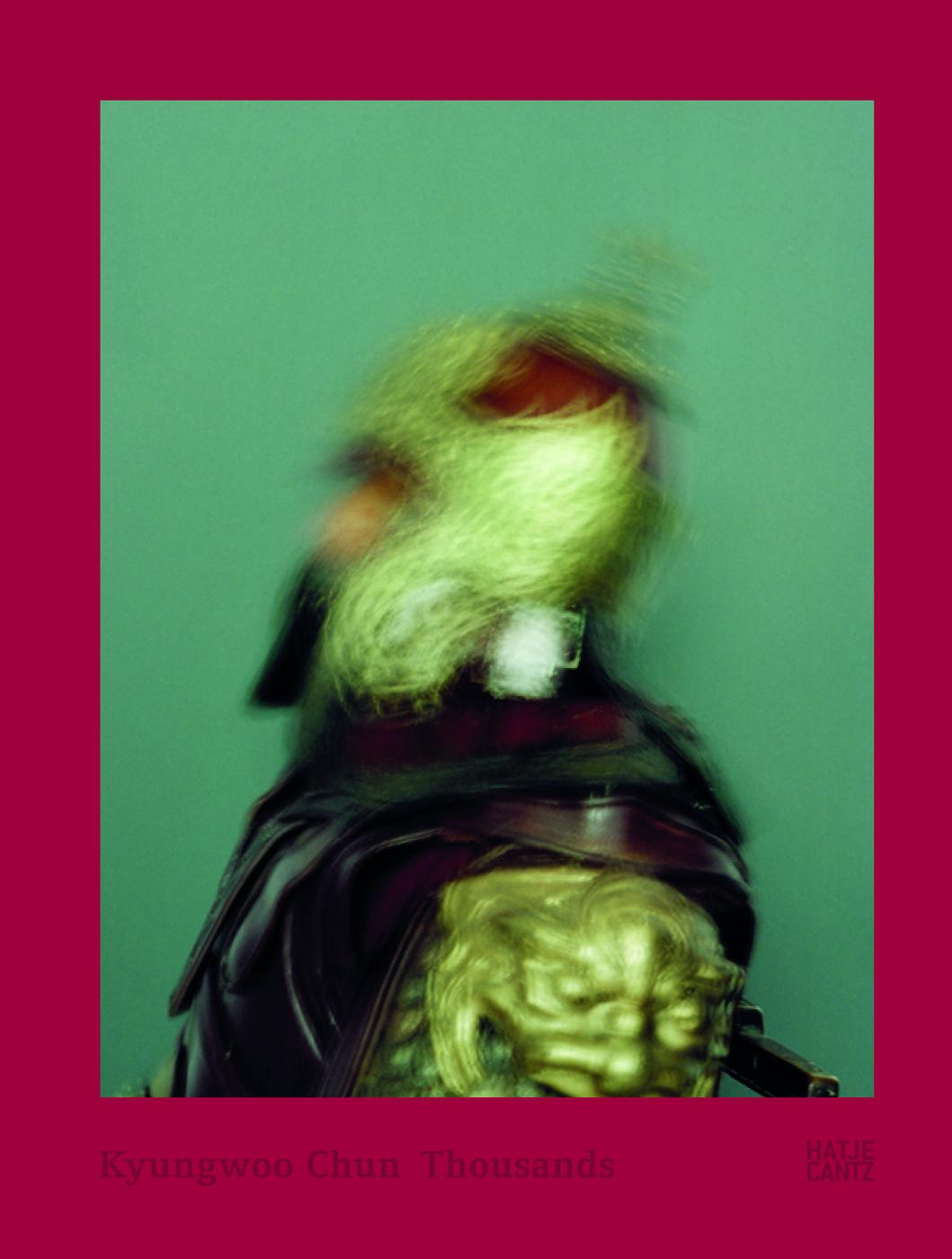

Kyungwoo Chun also constructed a (simple) studio in each of these villages in Henan, and he worked with long exposure times too. However, the sitters did not have to bother to maintain a still, almost cramped position, since the goal was not to achieve the most genuine, true representation of the people’s external identities. Rather, the aim was to take time, the ancestors’ space, the intuitive space, as well as the actions and communication occurring during the sitting and inscribe them into the long exposures. The intention was to create a vague perception—not information to be perceived. Chun’s portraits are a little bit like manifestations arising from out of a strangely muted red background. They do not show any precise details, but are concentrated on the essentials, so that we see the figures as people: boys, girls, men, women, but do not see any representations of individuals nor representations of status and power. Early portraits in western history were idealized representations of power. The age of photography brought with it the portrait of the individual. Chun, on the other hand, makes time portraits: portraits of time using slow, minute-long exposures of people. The portrait becomes a kind of vera icon—not of the person, but of lasting time, of appearance; not of individuality, but of the state of being human, of existence in general: typified intuitive space versus linguistic, formalized identification. In the series of different portraits, what remain of the General, in turn, are primarily expressive symbols of power, whereas the people who portray and play him for the forty-nine minutes recede into these insignia.

This attention paid to time, duration, and the processual, which is inscribed in Chun’s photographic history, asserted itself throughout the entire project. The creation of the photographs was not the end result. Each picture was enlarged and then brought back to the villages, where, whenever possible, each one was signed (name, age, village) by the person whose picture it was. Then the photographs were put into red packets and brought to Korea; from there, they were sent by post to Kyungwoo Chun’s address in Germany.

Chun emphasizes the processual, the flow; he highlights the context of the action, documents his project as if it were one long, continual performance. His videos are also about time, about the passage of time, about different tempos, as if we were watching time, listening to it like music, and experiencing continuity, slowness, and permanence versus explosive alterations of calm and speed.

A journey and a circulation through faces and history, a continuity of time, an action in the blink of an eye—all in a visual history by Kyungwoo Chun, which is about to become a traveling exhibition. Mostly immersed in a red that recalls neither Soviet nor Chinese communism, but probably the Chuns’ ancestral books. A circulation through the history of photography, too: a reduction of representationalism, of identification, as opposed to the opening up of the photographic visual space, its expansion, the emphasis on the duration of time in photography. “Believing is seeing,” writes Kyungwoo Chun somewhere else.

Notes

1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Politics and the Arts: Letter to M. D’Alembert on the Theatre, trans. Allan Bloom (Glencoe, 1960), p. 60.

2 Régis Debray, Vie et mort de l’image: Une histoire du regard en Occident (Paris, 1992).