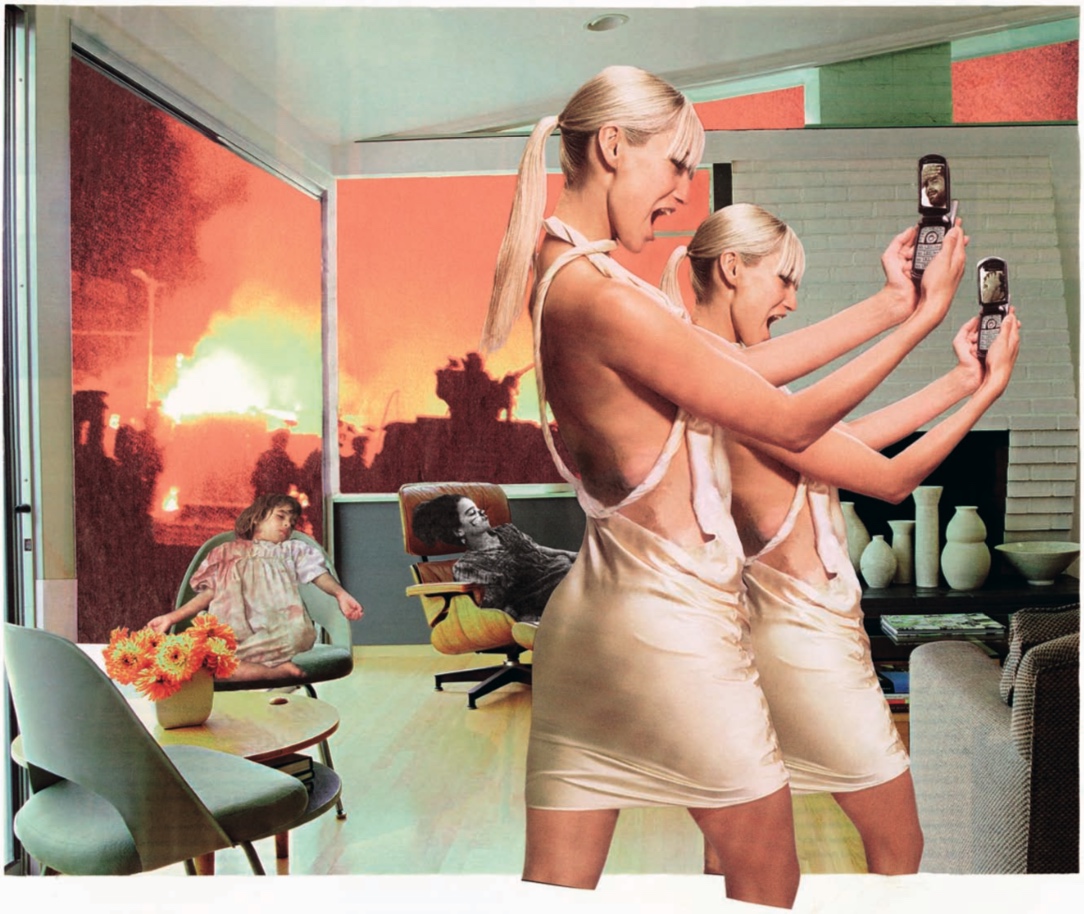

Shrilly and without restraint, three or four worlds wail at one another: battle scenes with tanks and infantry in front of an exploding ball of fire in the background. Two girls with closed eyes and the evidence of (fatal) wounds are draped over two lounge chairs to the left of the center. In the foreground, a blonde woman with bangs and wearing a skin-tight, backless dress—a cloned two pack (like a pair of identical twins)—starts sensationally. The two squeal hyperactively, excited over (two different) pictures on their cell phones; they hold up the phones with both hands, their palms half opened, in adoration. The three scenes are mediated by real estate—a salon with fireplace, chairs from the fifties and sixties, white vases in the style of the Bauhaus, with cinemascope windows onto the “garden.” In the meantime, this house is perhaps empty, has changed hands, fallen victim to the subprime crisis; certainly the house’s daughters, these blonde twins, have moved out in any case.

This photographic work is from 2004 and is called Photo-Op, Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful (New Series). Martha Rosler, the progressive American artist, created them during the second Golf War, as a revival of her own work Bringing the War Home, which she made in the late nineteen-sixties and nineteen-seventies, during the Vietnam War. In that work as well, she seamlessly combined the domestic harmony, the relaxed ambience of the American way of life, with the brutality of the war: a Courrèges lady from the nineteen-sixties, elegantly vacuuming without exertion, pulls back the curtains with a light hand and gazes directly into an unvarnished, horrific scene of warfare. Back then these were classic collages, skillfully cut out with scissors and glue; in the new works, Rosler combines the various elements digitally. Found footage, as it is called in film, has been taken, in this case, from the Internet or photographs from other media sources and then recombined and contextualized according to the artist’s logic. But also in the digital version, the collages are unrefined, without design finesse; rather, they continue to be sketchy and silhouette-like—with a hint of Brechtian alienation. Lighting and shadows are different among the picture elements and are applied in an intentionally raw manner. We are not meant to be blinded by these images, but to be shocked into reflection.

September 11 made Martha Rosler’s visual provocation into reality. The war “came home,” was suddenly and shockingly taking place directly on the front step, next to the drug store, behind the happy hour bar. Since the devastating civil war in the eighteen-sixties, the United States of America had not experienced a war on its own continent. Every conflict had taken place somewhere else, mostly across the ocean; the home remained untouched, the garden cared for. September 11 burst the American dream of invulnerability, of invincibility. Rosler’s new Bringing the War Home series was forced to upgrade itself massively in order to stay one step ahead of reality: the colors are more extreme, the confrontations more violent, special troops enter the living room, Abu Ghraib prisoners are confronted with runway models.

Photo-Op, the cell phone picture, goes one step further. It connects news images with excitement, with sexual stimulation. The woman is no longer sitting at home alone in a gray dress waiting for the letter to arrive, for her soldier to return home from the front dead or alive, as old photos and films tried to convince us; as a twenty-first century girl, she excitedly follows life on the front via her cell phone. Photo opportunities give a moderated report on the fortune and suffering taking place on behalf of the nation. Well-mixed and comfortably watered down, the horror at the front becomes a visual party drug—this seems to be the message of Martha Rosler’s acerbic image. Action and bad guys are cool and exciting; they are the kick, without which life would be really boring. With feedback to the front: “Be cool—a sexy blonde is watching you.”

Even this idea seems no longer to be only a provocative warning and message from the artist; it seems also to be reality. We are increasingly “speeding” from kick to kick, from excitement to excitement, jumping over ominous “downers” as long as possible. And any means is legitimate to keep this extreme excitement alive, to increase it more and more. What is an exciting fantasy in a game—a useful means—suddenly spreads, becomes brutal reality, a change in type of the most dangerous kind: high five here, mowing down there, megafraud here—the ultimate kicks of a peak-to-peak society. Images, bodies, accounts build up—until one day the eyes burst like popcorn, the body ripples like cauliflower. La réalité surpasse la fiction, sustainability ages quickly into a quaint term for oldies.