Walead Beshty decided early in his career to create, wherever he appeared, wherever he staged an exhibition and worked as an artist, portraits of those people with whom he worked, at least a few of them, those with whom he had worked closely in a particular place at a particular time. Over the past twelve years, he has created portraits of around 1400 people. Many of them through a formalised process: Beshty uses a small-format camera with analogue, usually black-and-white, 36mm film to photograph the people in his working environment. He has so far selected one portrait per person from the available image material. 364 of the approximately 1400 portraits were selected for the exhibition at MAST and printed, divided into 7 groups of 52 pictures each. The groups show artists, collectors, curators, gallerists, technicians, institutional workers (arts administration), and a variety of other professionals. Mixed in with the portraits we also find photographs of spaces, portraits of studios, exhibition venues, storage places, hotel rooms and conference halls.

In a certain way, the portraits appear standardised. They do not aim to give expression to the character, the being or the appearance, that is to say, the essence of a person, as studio portraits have always aimed to do ever since the beginnings of photography. Instead, the artist is far more interested in these people in their (and his) working environment, in the people and their function, the people and their role in the structures of the art world and the art market. One historical reference for this is the monumental project “People of the 20th Century” by August Sander. Sander was also interested in the farmer, the lawyer, the factory owner, the dancer as the symbiosis of human and job, human and role; he was less interested in the essence of individual people. However, he was working in the context of an even more strictly hierarchical society.

Two statements by the artist underscore this aim and process: “I don't think of any particular object as being particularly significant. It's much more the system that generates it” and “Objects have no meaning in themselves, rather they are prompts for a field of possible meanings that are dependent on context (…) That is, objects facilitate certain outcomes to arise that are not wholly predictable. These interactions accumulate over time, thus the meaning of an object is ever evolving.” Beshty presumably thinks this of every object in the world, certainly of every art work in the art world. And here in this large portrait project he also applies that notion to people and their functions. These people work in a certain context, exercise a certain function, are themselves, but also, simultaneously, themselves and their job. Barely have they left their workplace, then they are seen differently, are placed in different contexts.

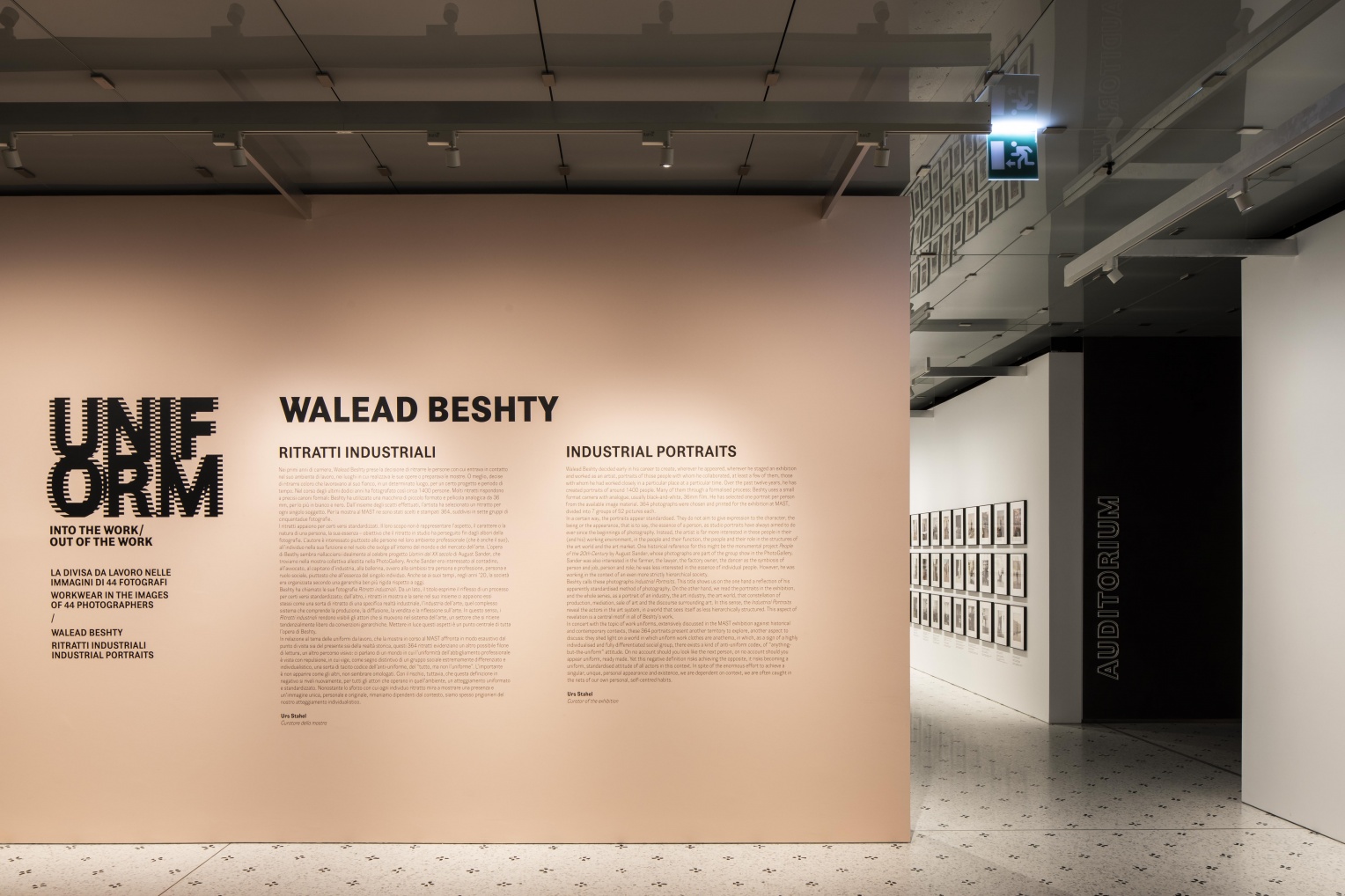

Beshty calls these photographs Industrial Portraits. This title shows us on the one hand a reflection of his gently standardised method of photography. On the other hand, we read the portraits in the exhibition as well as the remaining 1400-1500 (and growing) portraits as a type of portrait of an industry, the art industry, the art world, that constellation of production, mediation, sale of art and the discourse surrounding art. In this sense, the Industrial Portraits reveal the actors in the art market, in a world that sees itself as less hierarchically structured. This aspect of revelation is a central motif in all of Walead Beshty’s work.

His Ektachrome images, enlarged, reveal what happens when we are moved through the security checks at airports and light rays violently fall on the photographic film drawing sharp lines; his scratched, burst glass cubes that are packed up and despatched in Fedex boxes explore the transport conditions of goods; his copper sculptures reflect the handling of art, its packing, unpacking, transportation, moving around and placement. To ensure the traces of handling, the history of the objects are truly visible, the art handlers have apparently not worn gloves, which would usually prevent fingerprints being left on the smooth, shiny metal surface.

We can recognise in these three groups of works, as well as in the other works, how Beshty follows the traces of human actions, the traces of the processes of production and transportation, and how, through showing these traces, he reveals the system and how it works. Through his research and practice he offers us the opportunity to train our eye and see these things more clearly. As he himself has stated: “I don't want to teach a lesson or provide a recipe, but I actively try not to conceal. Power works by concealing how it functions, by enforcing a ritual, naturalising it.” Furthermore: "Art itself has the potential to democratise aesthetics and re-imagine art production as communal, available and non-hierarchical. I like the idea of demystifying aesthetics by communicating that we can all make aesthetic objects; it's not simply for those with capital or power." In the case of Industrial Portraits, he doesn’t just reveal these traces, he is himself laying down traces, the traces of his working life, its chronological and spatial processes. Here is Walead Beshty, actor and observer, actor and presenter in one. He documents the context that he has himself also been producing for 10-15 years. As such, it was important to him that he decided early on to embark on this series.

In concert with the topic of workwear and uniform, extensively discussed in the MAST against historical and contemporary contexts, these 364 portraits by Beshty present another territory to explore, another aspect to discuss: they shed light on a world in which uniform work clothes are anathema, in which, as a sign of a highly individualised and fully differentiated social group, there exists a kind of anti-uniform codex, of anything-but-the-uniform attitude. On no account should you look like the next person, on no account should you appear uniform, ready made. Yet this negative definition risks achieving the opposite, it risks becoming a uniform, standardised attitude of all actors in this context. In spite of the enormous effort to achieve a singular, unique, personal appearance and existence, we are dependent on context; we are often caught in the nets of our own personal, self-centred habits.