«Infinity will be vanquished, not by machines, but by mankind itself. (...)

For we are truly the cogs in the wheel; the industrial machinery is but a caricature. We are abandoning our very existence in favour of the daily increasing number of things.»

Saint-Pol-Roux

Today’s world constantly assails both memory and gravity. Everything seems to be in flux. Business plans are short-term. Invent, develop, produce, transport, sell, diversify, decomission, re-acquire, rename, shelve, change the management, and finally go for fusion. Then the whole game starts afresh, at ever higher speed, higher risk and higher potential profit.

For centuries, things moved at a steady pace. People took their time. Time itself was sluggish, and things needed to mature, like a good wine, or simply take their course, like convalescence from an illness. In the modern era, this natural timespan was superseded by a human timespan in which events moved more swiftly, overtaking each other, jostling and pushing and nudging each other aside, until we arrived at what Aurel Schmidt described as the «non-stop society». The watch-hand may mark the seconds and the minutes in the same old tempo as it has done for centuries, but the pulse has quickened, the blood pressure has risen, and the power of motion framed within each moment of time has increased. Machines hammer out their beat incessantly, 24 hours a day, never resting, never complaining. Industrial output has accelerated over the decades, outpaced only by the gigantic explosion of computerisation, digitalisation and data networking.

«Speed», as the visionary French poet Saint-Pol-Roux wrote in the early years of the twentieth century, has become «the hallmark of progress». He railed that «the machine is the masturbation of man» and that mechanical acceleration had become «madness in a straightjacket». And that, «Since the advent of mechanical velocity, humanity has come to a standstill.»

Speed, combined with impossible promises of ever new forms of salvation, and with ever-increasing floods of new images, new visions, new products, became the all-devouring magical motor of capitalism. An eternally blinking «black hole» on earth.

As a rule, the further the sites of production and sale are separated from each other, the higher the profit. Timescales shrink and transport routes expand. In between, huge cargo ships ply their course – vast container cities transforming, on their long voyage, the 2-euro work of a seamstress on one side of the world into a 2000-euro gown on the other. If the goods are perishable, flight routes and refrigeration chains accommodate them. During the journey, the stock exchange constantly bets for and against the vessels and their cargo, as though the entire world were merely a game – a neverending race. The vast distances between the hubs of planning, development, production, sales and marketing replicate the gulf of alienation between anonymous companies, capital or financial enterprises and the actual needs of real people and real workers.

We are all part of this cycle, whether gambling on profit and loss or making our way, happily not, to our daily workplace. In both of these spheres, over the decades, the emphasis on speed and productivity has been constantly ramped up. Ever since the beginning of industrialisation, we have been accelerating at a dizzying pace, increasingly raising our expectations and demands, both on others and on ourselves. As little time as possible, covering the biggest possible area, achieving the highest possible profit with the lowest possible input – those are now the parameters of success.

There is only one area in which we are slowing down, and seeking standstill: migration. Even though we know full well the appeal of advertising, the repercussions of colonialist crimes, and the depth to which potential profit margins are ingrained in all our minds. The losers in the modern world, both local and global, are being radically sidelined. The exhibition highlights the contrast between the immense powerhouses of ever-increasing acceleration and the fetishising of fast vehicles on the one hand, and the braking, slowing and stopping of people and migrants on the other.

From Markowitsch’s Psychomotor to Doisneau’s Renault photographs, Edgar Martin’s BMW paintshop, Mula’s racing cars and Luciano Rigolini’s three-part car fetish temple, what ultimately brings the exhibition together in the end is the strident dissonance of their clash with the wall on which the complex installations by Ulrich Gebert and Xavier Ribas address the issue of migration and nomadic life.

These diametrically opposed and contrasting energies are strongly palpable in the images here. In Ribas’ work, we look directly at the demolished concrete panels of a former factory site, destroyed by the power of the owner simply to ensure that no vagrants or nomads can possibly stay there. In Gebert’s work, it is the darkness in which travelling migrant workers stand in line to beg for a job, contrasting with the luminosity of heavily laden orange trees.

The pendulum is a potent symbol of the passing of time. It is also a symbol of changing opinion, shifting viewpoints and the transformation of previously held convictions and behaviours into their opposite. We even think of commuting in terms of a pendulum that swings from early morning suburbia to city-centre workplace and back again, exhausted, at the end of the day, only to sleep. The pendulum is a metaphor for the traffic that never ceases, and for the endless exchange of commodities, either for other goods or for money or even for promises.

In 1851, the physicist Léon Foucault unveiled a long and slowly moving pendulum in an astonishingly simple illustration of how the earth rotates around its own axis. «And yet it moves!», as Galileo is said to have declared – not just around the sun, as he and Copernicus had already proved, but also around its own axis, as Foucault demonstrated here. The earth’s rotation around its own axis encapsulates, at core, the vast dynamic generated by humankind with our tools, machines and instruments over the past two or three centuries. All is inexorably and restlessly geared towards start-up.

The exhibition Pendulum – Moving Goods, Moving People clearly presents, by way of contemporary and vintage photographs from the MAST collection, just how much power we lend to this movement, and how inventively we have developed ships, cars, trucks, railways, aircraft and data in order to conquer the world and to put business, trade, production, sales and transportation at the centre of our existence. It shows how we have gathered speed as we spin ever faster in a furiously accelerating pirouette that will see us either bore right down into the ground or ascend to the heavens.

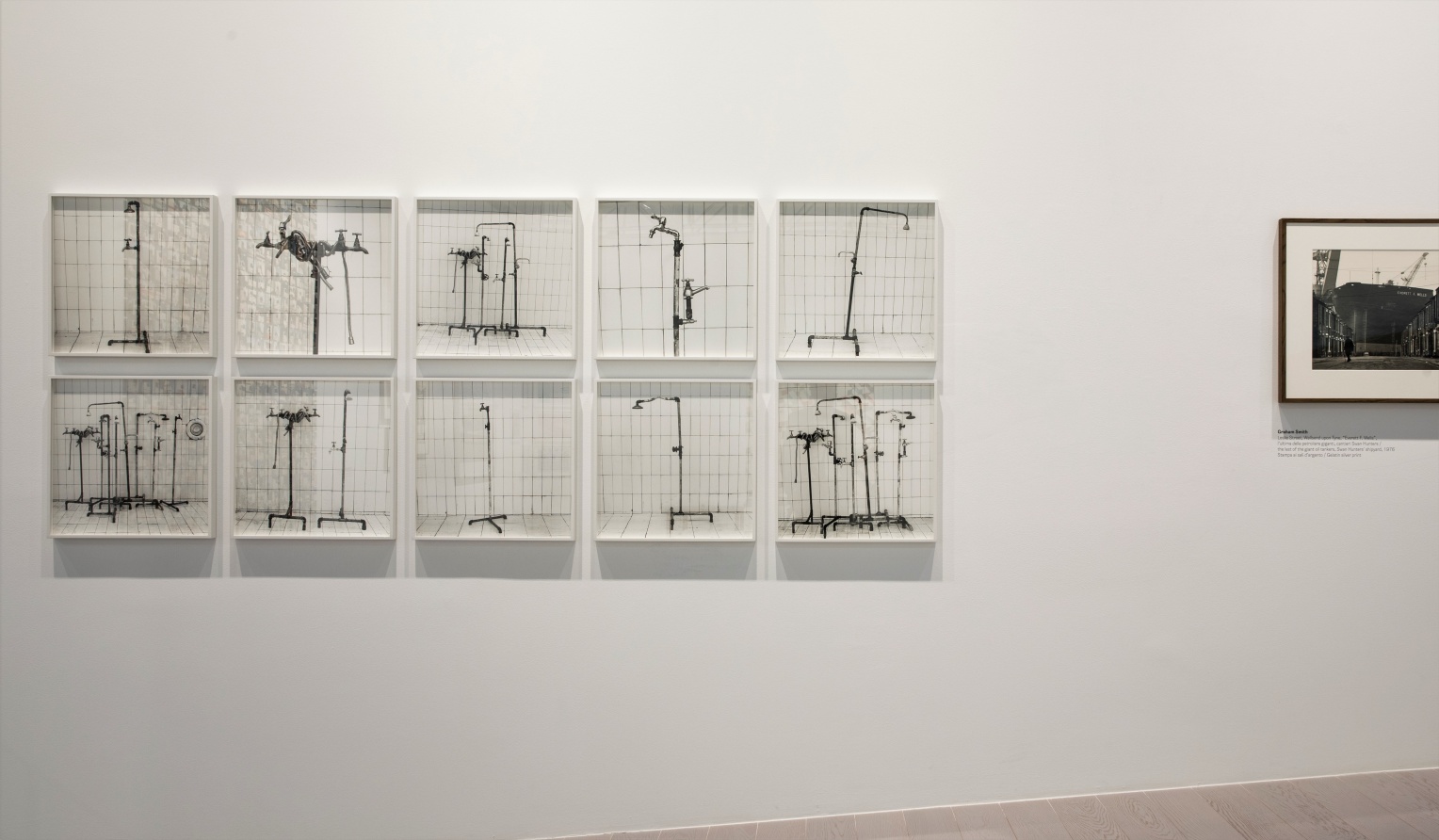

Sonja Braas‘ container piece, Annica Karlsson Rixon’s trucker epic, and Yto Barrada’s plumbing block are all striking visual expressions of transportation and movement, of mobile goods and mobilised people. Helen Levitt captured the mood of commuters on the subway in the 1970s and 1980s in dense, black-and-white close-ups, while David Goldblatt’s dark and brooding images tell of the tough four-hour bus journey to work and the even tougher four-hour journey back after a ten-hour shift. Jacqueline Hassink photographs today’s commuters in seven global cities, showing how they all travel twice – to and from their place of work – and at the same time virtually, via the smartphones and tablets at which they are staring intently. Finally, Richard Mosse links global trade with migration in a work that is 7m 30cm long. In his Skaramaghas from the Heat Maps series, hundreds of containers fill a sprawling dockyard site. On the left, his heat camera, an optical weapon that can detect temperature differences at a distance of 30km, records the global commodity transport, while on the right, the same containers are used as shelters for migrants. Migrants caught in a place where they do not know whether they are coming or going, anxiously wondering whether they will be allowed to move on or be shipped back again. The entire system in one image.

Paul Virilio, the cultural theorist and dromologist renowned for his writings on velocity, speaks of TRANS-port, TRANS-mission and TRANS-plantation, noting that speed not only brings quantitative changes, but also qualitative changes to our lives, so revolutionary that we might well imagine Foucault’s pendulum one day taking on a life of its own and suddenly hurling itself up and away, signalling life’s fundamentally altered parameters. Simply because the balance of energies has changed too much. Destination unknown. In a black-and-white photograph by Dorothea Lange, potential disaster is limited, for the time being, to the steaming and dented wrecks of cars, while a truck in the background is probably bringing more new ones.